Andrea Blanch: You have been called the greatest living photographer of America’s social and geographical landscape. How did you choose your subject, and why?

Alec Soth: Well, first of all, I’ve been called a lot of things! That’s just one of them. I certainly did not have ambitions to be some monumental recorder of America or anything like that. I came to photography from the kind of true documentary-style photography tradition, you know. The whole Walker Evans lineage. But I was a very introspective person and, if I’m honest, I was more interested initially in exploring myself than society, or American society. So I just think it’s inaccurate to claim that was my motivation. I’m not saying I didn’t make some sort of record of things along the way. But that wasn’t my intention.

AB: You’ve said that vulnerability is the most beautiful thing. In regards to the subjects that you choose, do you find more vulnerability in those people than with, let’s say, more privileged people? Or are you attracted to it as a documentarian?

AS: That’s an interesting question. It’s a question that hits on photography in general. Photography is so much about access. Essentially, it is quite challenging to get access to people of money. People of money often have gates; they have literal gates and they can have emotional gates as well. Whereas, if you’re driving around in Mississippi, not a lot of people have gates. A lot of people are just sitting out on stoops or whatever, and access is easier. So it wasn’t intentional—and I think it’s ethically problematic—but yes, I do think that I was able to access that kind of vulnerability more easily from people without means.

AB: I have a couple of questions about Fashion Magazine. First, you said you always wanted or needed an excuse to shoot fashion. Why do you need an excuse?

AS: Just as a young photographer, I was so impressed by fashion photography—technical skill, efficiency, and constant creativity. I was curious about what would happen if you threw me into that world. And the truth is, I’m not a great fashion photographer. Because the bulk of what it’s about is actually clothing. And as it happened, I’m actually less interested in that. But I was interested in the phenomenon of fashion photography and sort of playing in that arena briefly.

AB: Did you find any vulnerability in that world?

AS: Less, because of the way in which I was working. It was a real shift in my style of working. I had come up doing projects by myself, working in isolation. But when I did fashion, suddenly there were teams of people—people arranging things, sending me casting things, Polaroids, all that stuff, like machinery. Thus, it generally prevented that kind of intimate relationship. One thing that I found fascinating along this line is that at a certain point I said, “Okay, no more models. I don’t want to work with models anymore.” Models are professionals. They have a switch that they click and they do the model thing. It looks amazing to the camera—you’re just like, “Wow! That was beautiful!” But there’s no vulnerability there, understandably. This is something I’ve found true of people who get photographed a lot. It’s just a job. It’s easier to glimpse something raw and real with people who are less photographed in a professional context.

AB: In regards to the third Fashion Magazine called Paris Minnesota (Magnum Photos, 2007), was your sense of wonder as great photographing in Paris as when you were shooting the counterpart in Minnesota?

AS: Well, there was a sense of wonder. I mean it was like, “Wow! Look at this situation I’m in!” But it was a total fish out of water situation. I got kicked out of my first fashion show because I didn’t understand the backstage photo protocol. I was meeting different people, you know, who are like big cheeses. But I didn’t necessarily know who they all were. I thought it was funny and entertaining, and this is sometimes the way I use assignment photography; it’s just for the experience, and to be given a glimpse into other worlds. But I wasn’t going to dedicate my life to that work. I wasn’t going to move to Paris and become a fashion photographer.

AB: On one hand you say that you drive around looking for your subjects, and then on the other hand you say that assignments like The LBM Dispatch have different parameters. Can you explain that a little further?

AS: Well part of it is just this evolution of my process. It’s not any one thing—it’s changed from project to project. I confronted this contradiction of sorts very recently—I was just on a collaborative project down South and it was right in the neck of the woods that I worked in for Sleeping by the Mississippi (Steidl, 2008). I had to come to terms with the fact that I’m really not the same person. I’ve had so much experience since then that I don’t approach the world in the same way anymore.

When I started out I was pretty timid, always alone, and quite naïve in some ways, but in a hopeful way. I was wide-eyed. Then I got thrown into many different situations, working with lots of people. The thing is, when you work for a magazine, you have to make a picture. If I’m wandering alone doing my own thing and I see someone, I can start to talk to them. And then I can change my mind. But if it’s a magazine and they’re expecting a picture, I have to produce that picture.

So I’ve had to go through that and learn how to do those things, which inevitably changed my mode of working. Like with The Dispatch, I’m working collaboratively with a writer. Sometimes there are things that interest him that are less interesting to me. And of course I’ll pursue it because we are collaborating, that’s just the nature of collaborating. It’s been a number of years now where almost all of my work has been collaborative. But I’m actually shifting back to working alone again.

AB: Was Songbook (Mack Books, 2014) collaborative?

AS: It truly was, because the work is really pulled from The Dispatches or from my work with the NY Times. As a book I was offering it myself, but so much of the work was made in collaboration with others.

AB: In regards to Songbook, why did you choose to pose as a journalist when you didn’t feel the need to do that in other projects?

AS: Songbook has a funny history. I had been doing this very internal work, and I suddenly had this desire to work out in the world again. I called my friend Brad Zellar, who had previously been a newspaper journalist, but has a deep understanding of art photography. And we’d go out for the day to do an imaginary newspaper assignment. That was it—just as an experiment. We had so much fun doing it so we did more and more in Minnesota.

We didn’t know what we were doing. It wasn’t called The Dispatch yet—it wasn’t anything, but it grew into something. I had this opportunity to speak somewhere in Ohio, and I said, “Hey why don’t we take this on the road? Let’s try driving around Ohio.” We actually published that dispatch. Then it was years of working, we eventually did seven of these dispatches. But at the same time I was also doing New York Times work, and other sorts of side projects, and making all of this work. I wanted these pictures that I was making to have this other life—a life that was separated from the text component.

Then Songbook emerged. The reason we posed as newspaper people, first of all, is because we were eventually publishing our own newspaper. The newspaper and journalist metaphor was helpful because the work itself was about engaging socially, and the newspaper is an understandable way of communicating social information. So that was the strategy and that was why we distributed it in that way—only 2,000 copies of each newspaper, and it wasn’t really news- print in the end. But that mode of operating seemed worthwhile. Plus, the work itself was looking backwards in a lot of ways…looking back to another time, thinking back to another time in America, and another time of communication—that being the newspaper.

AB: I read that you like the aggressiveness of a flash. Why do you think that was good for this assignment? Do you equate flash with journalism?

AS: In a sense, yes. I had once worked as a suburban newspaper photographer, and of course I’ve done years of assignments. One of the things that you learn as a photographer is that if you’re on assignment, as I said before, you have to come home with a picture. Especially in a newspaper context, you’re thrown in a lot of different situations. The mayor is giving a talk and the sun is behind the mayor and you’re only allowed to stand in this one little area. How are you going to get a picture? You have to use a flash. You know you’re not going to create a Jeff Wall and restage this thing for a month and a half. So the flexibility of the flash makes sense. In a similar way, black and white has this efficiency for reporting purposes because it just cancels out that factor. So if the mayor is wearing a yellow suit, and looks ridiculous or something, you can neutralize the scene in a way. So I liked that, but I was also making reference to newspaper photography of the past and evoking that aesthetic.

AB: In Sleeping by the Mississippi, how did you get permission to shoot inside the penitentiary in Louisiana?

AS: I did write a letter in advance. I had no credentials, so it was kind of miraculous. It’s funny; I’m not that old, it wasn’t that long ago, but everything before 9/11 seems like a more innocent time photography-wise. It has nothing to do with 9/11, but security everywhere changed and suspicion changed. I also just felt, with Sleeping by the Mississippi, I had so much good luck. Everyone said yes. It’s a feeling that I have, having just been in the South again, that there is just a warmth and openness. It’s so much easier photographing in the South. And some of that is for economic reasons. But a lot of it is cultural.

AB: Are you still shooting with an 8×10?

AS: No, not so much. I mean I do it project by project. It’s worth noting that my second project, Dog Days, Bogotá (Steidl, 2007), was medium format—a small camera. And I’ve done plenty of small projects. I did a book with a disposable camera. I’ve done all sorts of wacky different things. But my early work was identified with 8x10s, so you know, I have to live with that. My theory now, or my way of working, is to try to think of myself as functioning more like a filmmaker because I’m so project-based. Songbook was photographed medium format digital. And who knows what the next thing will be photographed with.

AB: Why did you choose a muted palette?

AS: I don’t want to pretend I was overly conscious of it, but I was conscious of it. Photographers’ works that I studied, that I’d really responded to, had this kind of softness of color, not an exaggeration of color. There’s this funny thing with Eggleston—everyone talks about “The Red Ceiling” picture as being the quintessential color photograph. But it’s actually pretty atypical of his work. If you look at the great color photographers, they generally got past this point of, “Oh wow! Oh purple, I’ll photograph it,” and dealt in experiencing the mood and color of something overall. So I responded to that kind of softer, more nuanced quality, and part of the thing about using 8×10 was there’s evenness. There’s a sharpness to everything, and everything’s rendered with evenness. So hard shadows work against that in a lot of ways. And hard light works against that.

AB: Well I think it lends to the mood of what you’re capturing. Speaking of people that influence you, I read that Robert Adams and Diane Arbus influenced you early on. Can you give examples of where we see that in your work?

AS: Influences are a funny thing. There are the really obvious ones: Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld—those were big influences. I think you can see Arbus in the portraiture. There’s a physical parallel with my best known picture, “Charles” from Sleeping by the Mississippi (the guy with the airplane), and Arbus’ “Child with Toy Hand Grenade in Central Park” (1962). I think Robert Adams is a much tougher one to identify, and part of the Adams influence is that it’s not a direct influence. I’m sort of in an imaginary conversation with him all the time. And I would say that’s true of Robert Frank as well. There’s the road photography thing, sure, but visually you don’t see a huge overlap. But I have sort of an imaginary conversation with these people.

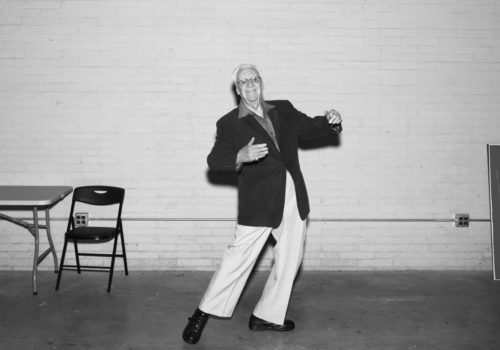

AB: Speaking of the photograph “Charles,” with the airplanes, I also read that when you photograph men you feel there’s a playfulness and awkwardness to them. Do you think that “Charles” shows that?

AS: It’s interesting how that picture has become “The One.” But in a lot of ways it makes sense to me, because there is this funny sort of self-portraiture wrapped up in it. I don’t know if I’m projecting it on to him. There’s something slightly comic and maybe a little sad about it. If I were to make a self-portrait it would probably have both those qualities as well.

AB: When you talked about photographing women, and you said that at one point you were coming to terms with how you honestly see and perceive women. I’m thinking of the period where you photographed Florence in the bed (Paris Minnesota). I want to know if you’ve come to terms with that. And how that has informed your work or how your work has changed?

AS: Yeah it’s a really tough question. It’s actually one of those things that I have been thinking about and engaging with. When I’m photographing, I photograph strangers, and I’m responding in large part to their physical presentation of themselves and that’s a different thing. I tend to identify more with men and if you want to make it more incriminating, white middle-aged men. Women I often see as somewhat different from myself. I just have an awareness of that. It’s problematic and all of those things, but you know…I’m just being honest.

AB: Why do you think it’s problematic?

AS: I think it can be, in terms of how one represents women. Photography is the art of objectification. It’s all about surfaces. It’s really hard. You’re not getting everyone’s personal history. So when I put a picture on a wall, part of it is allowing viewers to confront their own issues about how they perceive people. How they perceive overweight people, or thin people, or poor people, or rich people. It’s kind of a springboard for a zone of issues and to confront those issues.

AB: You had said you romanticize or sexualize women.

AS: I think there’s an element of that.

AB: The only one I’ve seen like that was this woman Florence, because she was in bed and you see her breast. Do you sexualize them because there is an attraction there?

AS: This relates to the fundamental question that I’m always asked about portraiture: why do I pick this person over that person? And I always equate it to sexual attraction, but at the same time it’s not sexual attraction. It’s something, a physical thing. I respond to that person. I’m always asked, “What is that thing?” And I don’t know, it’s like why are you attracted to a person across a crowded room at a bar? If you analyze it, it’s cultural; it might have to do with what your mom looked like or what your sister looked like. You know, it’s so complicated. My attraction to people that I photograph is a complicated thing, and I’d be lying if I said it was the same thing between men and women. It’s just not. And it’s not the same thing when I’m photographing in a different culture versus my own culture. I respond differently in different contexts, I guess. I’m just being honest about it.

AB: Do you really photograph a lot in different cultures? In different countries?

AS: A fair amount. I’ve been photographing in Japan lately, but I don’t do major projects on it. But I did a thing in the Republic of Georgia, in China, in South America.

AB: I only associated you with America.

AS: Totally, because I’m more comfortable doing it. I’ve never produced big projects out of those other works because I’m somewhat uncomfortable with the idea of photographing and making work in other places.

AB: What do you teach?

AS: I don’t teach much. But I am really involved right now in this project with teens. It’s called the Winnebago Workshop—it’s actually an art school in an RV. I take the kids out and have them meet other artists. I think what I’m pretty good at is going out in the world and exploring while also exploring internally. Being pushed out into the real world can be really powerful creatively, and I think there’s a timidity that a lot of artists have. In the smart phone era we forget that there’s a world, a physical world. But I’m not a great teacher. I just think of myself as a bus driver.

AB: In regards to the timidity you mentioned, you said that you’re less nice now, and that pushing into the world and confronting people made your work so much better. Can you give an example of what that work might be? What time period was this?

AS: I have a reputation of being nice. And I’m not sure if that’s totally true. I don’t think I’m an asshole, I just don’t think I’m Mr. Nice Guy. There’s a great quote from Weegee. Someone produced an album where he is talking to students. He says, in his wonderful accent, “You got to get past the point of just photographing your friends and family. I was scared to, but you got to learn to go out in the world. You can’t be a nice nelly.” And that’s what my feeling is. Frankly, sometimes it’s annoying people. But that act of disruption can lead to something really beautiful. You just have to take the risk of being annoying.

AB: I read that you started with staged photography, and then moved into documentary photography…

AS: I actually came to photography through painting and sculptures, in the beginning. So I didn’t begin through Magnum and photojournalistic “save the world” stuff. And I did do staged photography. If you broke it into a spectrum, I would have been on that side of the spectrum.

AB: Would you consider that some of your portraits are staged photography, in that sense?

AS: Yeah. I take the stuff that’s there and I move it around and play with it. I have no problem with that. I see all this stuff as a spectrum, so there are gradations. I’m not casting models and decorating sets. I’m somewhere in the middle, which for me is the exciting place, a more honest place. The presence of the author shapes the work.

AB: I read that Prince bought your house. In an interview someone asked him, why Minnesota? And he said, “It’s so cold that it keeps a lot of the bad people out.” Having grown up there, how has Minnesota influenced your work? Why stay there? It’s so cold!

AS: I went to Sarah Lawrence College, and I knew I was not an East Coast guy. I revived my feelings about Minnesota over the years. But it’s not like I have to live here, like it’s my duty in life to live at home. Circumstances took hold, and the roots started digging in. It’s also hard to move with kids. So there’s that, which is a boring answer.

I do think it has a huge impact on my work for multiple reasons. Particularly, not living in New York or another art hub affects me because I can get away from the influence of things. I don’t have all of the shows, the buzz, and this and that around me. I can go and engage with that world, but I can leave it very easily. It’s important for my sanity.

AB: You had said that small-town, Middle America is not just strip malls. Each place is different and it has its own subtleties. You mean the people, right? When I’ve driven through Middle America it all seems the same.

AS: This is why you should come on my bus, because I would show you how it’s not. A few days ago I went from Greenville, Mississippi to Bentonville, Arkansas, and I might as well have gone from Texas to San Francisco. It was so culturally different. The people looked physically different, the economy was different, the racial breakdown of the people was different. We don’t see this because we drive on freeways, we pull off, and there’s the hotel, and the Burger King. You just have to go further in, and you have to talk to somebody. Then, very quickly, things change. There are different regional qualities and that’s not understood broadly in America, or at least in the media.

AB: I’d like to talk a bit about Niagara (Steidl, 2006). How long did it take for you to decide what angles you were going to take of the falls? The very first one that I saw looks like you’re just about to fall over.

AS: The crazy thing about that picture is that it’s the picture that 8 billion photographers have made. Every person stands in that exact spot. And it’s one of my best selling pictures.

AB: You photographed the images of the falls, cheap hotels, portraits of ordinary couples, and then you have these love and hate letters. Did you ask those people to write them? Or did they already exist?

AS: They already existed. It was quite a challenge to get them. That’s what I’m talking about with overcoming one’s timidity. It was so uncomfortable approaching people and having to ask if they had love letters, just because there’s no context for that.

AB: Would you say that Alec Soth’s America is about melancholy and loneliness?

AS: You know, I’m uncomfortable with such broad statements, but I do think that America has something to do with treasuring individualism, which I love. And freedom of movement. But it also comes at a price and part of that price is solitude. But I kind of love loneliness.

AB: I want to tell you that the picture you took in the cave with the makeshift coat rack and hangers was just one of the most beautiful images I’ve ever seen in my life. It so touched me, I can’t even tell you. John Szarkowski said, “It isn’t what a picture is about but what it’s of.” Could you explain the difference?

AS: That’s a tough one, and I love processing Szarkowski quotes. He also talked about how photography, on a mental level, is just pointing. It’s just pointing your finger, and saying, “look at that.” And when you point to something you’re not showing the molecules, you’re not showing its history, its ‘everything.’ You’re showing this thing in this context, in this fraction of a second, in this light. Everything beneath the surface exists, but it’s imagined. And one has to come to terms with that.

As a photographer, I’ve learned over and over again that I’m actually not photographing the thing; I’m photographing light bouncing off of the thing. For example, if you ever have to reshoot a tree and you go back and photograph it the next day, it’s a completely different tree. And so I would actually add to Szarkowski’s quote and say, “it’s not the thing, it’s the light bouncing off the thing that you’re photographing.”

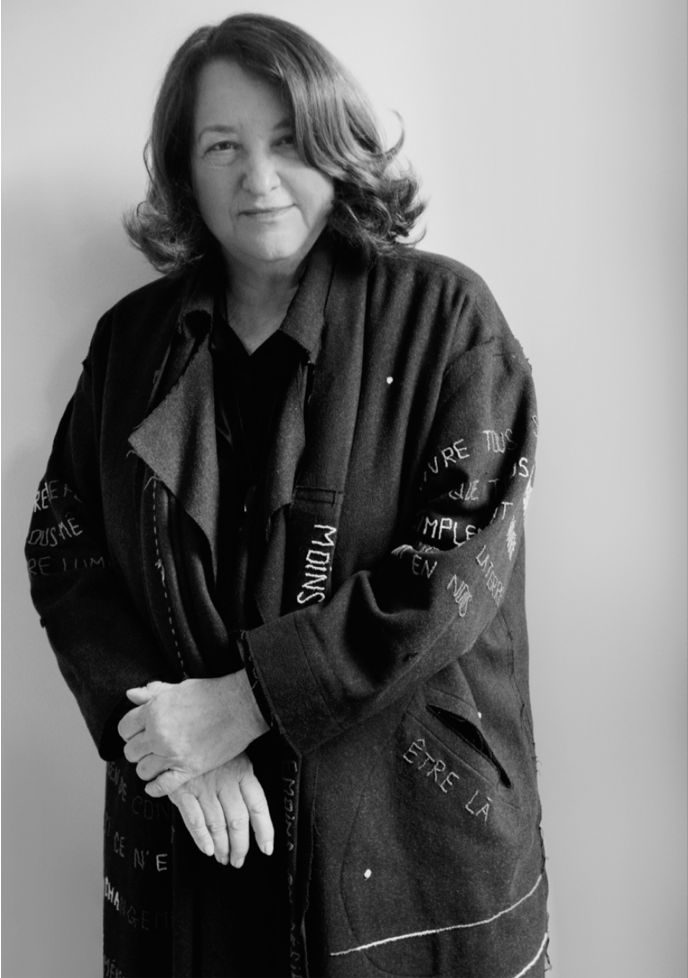

Interview by Andrea Blanch

Andrea Blanch is the founder and editor in chief of Musée Magazine, a photography publication based in New York, and a fashion, fine art and conceptual photographer.

This interview was published in the issue 15 of Musée Magazine in July 2016.