… et labora / Foreword

The XIXth century was that of the advent of Vincent van Gogh’s work but also that of the appearance of the photographic medium, which quickly became one of the most important tools of our modern societies.

Aware of this interest, Ruth and Peter Herzog began to collect anonymous photographs from the early 1970s, thus constituting a collection which today brings together nearly 600,000 documents. The exhibition “… et labora” presents a fraction of this rich collection, having drawn from it photographs and albums related to working. From the views of factory interiors to work in the mines, agricultural tasks or small trades in the cities, the images in the Herzog collection offer rare testimonies of an era whose upheavals are still being felt. today.

If these photos give pride of place to anonymous photographers, the exhibition also presents works by contemporary artists who constantly question themselves, both formally and conceptually, about our ways of working and our modes of production. Work was already a major concern for Van Gogh – as an artist but also as a witness to a European society in the process of industrialization.

Today, the Herzog collection is kept in three separate places: at the private Herzog foundation in Basel, at the Jacques Herzog und Pierre de Meuron Kabinett in Basel as well as at the Swiss National Museum in Zurich. The work carried out by these three entities guarantees precious digitization and archiving for a collection whose artistic qualities and scientific importance represent a gold mine for generations to come.

We are particularly touched to be able to present this collection in Arles, as it allows us to enrich a fruitful dialogue with the city’s past, lulled by the history and heritage of the former SNCF workshops where Luma is now installed. But it is also with joy that we perceive through this exhibition the continuity of the dialogue maintained between Arles and photography.

Exhibiting the photographs from the Herzog collection in dialogue with the works of contemporary artists was both fascinating and instructive. This would not have been possible without the warm support of Ruth and Peter Herzog, without the team from Jacques Herzog und Pierre de Meuron Kabinett with M. Paul Mellenthin and of the Swiss National Museum with Mme Ricabeth Steiger. Thanks also to Mr. Andreas Gursky and the Gagosian Gallery, the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, Mr. Greg Hilty and the Lisson Gallery, the Sprüth Magers Gallery and Barbara Gladstone as well as Hauser & Wirth, the Max Hetzler Gallery , at mother’s tankstation and at Klosterfelde Edition. A big thank you also to the artists Emmanuelle Lainé and Michael Hakimi for their confidence.

We also wish to extend our thanks to the Mucem and the Museon Arlaten for their ex-voto loans. Finally, thank you to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam for their precious and faithful collaboration.

Maja Hoffmann

President of the Vincent van Gogh Arles Foundation

Bice Curiger

Artistic director of the Vincent van Gogh Arles Foundation

————————————-

With the eye of the collector

An interview with Peter Herzog by Barbara Basting

Barbara Basting: You once spoke of the birth of photography as a Big Bang …

Peter Herzog: The birth of photography was indeed like a Big Bang: suddenly, without being an artist, you could fix everything, the most sublime and the most banal, the living and the dead, the sea of ice and the desert .

BB: Your collection is very large, from a historical, thematic, aesthetic point of view …

PH: Until the 1970s, I was not very interested in photography. Then, at a Zurich flea market, I came across a photo of spinners sitting in a circle on a terrace, working together and chatting. It is difficult to determine who these young women are, pupils of a school for young girls, or peasant girls who meet regularly?

I was not only fascinated by their activity, however. On this photo with shades of brown appears a white dog. I immediately thought of Wilhelm Busch’s widow Bolte’s dog, and this comic shift also fascinated me.

We also see an old woman; the young girls spin and the old woman unwinds the thread. What is told is, so to speak, unwounded at the same time. The meeting of these different levels – documentary, aesthetic, allegorical and comic – suddenly opened my eyes to what photography is, or can be.

BB: The French philosopher Jacques Rancière writes in his reflections on photography1 that photography has recently become an important art precisely for this reason: on the one hand it is the trace of something consisting of several layers and difficult to grasp, on the other hand it remains a simple document. This polarity seems to interest you…

PH: Here we are touching on Roland Barthes’2 “punctum”: if this image is probably nothing special for someone else, it has touched something in me. If we looked for the reason why with the help of psychoanalysis, we would quickly find ourselves in the story of my life. This snapshot echoes some of my childhood memories, including those of my grandmother and my reading of Wilhelm Busch.

BB: Why do we make personal connections with photography more quickly than with the visual arts?

PH: Most of the time, photography is not polluted by the artist’s desire to represent himself.

BB: At the first universal exhibitions, for example that of 1855, in Paris, photography was presented in the “Industry and Techniques” section. Did it occupy the same rank as painting and sculpture at Art Fairs?

PH: At the time, it was a challenge for the public. You could see magic there: suddenly, an image appeared from nothing. It was also a replica of reality, more precise than the best miniature painting. But it was tiny. What was revolutionary was this format and the subtle colors, rarely recognized as such.

What was decisive was that the photographer Gustave Le Gray made his salons on boulevard des Capucines available to the “cursed painters”. The Impressionists, this clique of daubers proscribed by the jury of the Official Salon, also found refuge with Le Gray who saw that painting should evolve in the age of photography.

BB: What distinguishes it from painting is the immediacy of the picture …

PH: In fact, unlike paintings, photographs are often images that are born in the moment, “stolen” images. This is what makes them so charming.

BB: You broadened the aesthetic spectrum early. Beside the incunabula, alongside pictures of Nicéphore Niépce, Felice Beato, Eugène Atget, we also always see comparable subjects, similar images of unknown photographers. I am thinking of these absolutely fascinating photographs of passers-by in Paris at the turn of the 20th century, which remind us of Jacques Henri Lartigue from afar. They are however less refined and at the same time much more captivating.

PH: For a collector, confrontation is a principle. Experts have already criticised me for mixing pearls with the worst dross. However, there are only two types of photographs in my eyes: those with captivating content and those without messages. And everything interests me. When you say it that way, it’s immediately taken for a lack of critical thinking.

However, I can emphasize that I don’t like false images. I will name those of Helmut Newton as representative: they seek to have an effect, and claim, with primitive means, to have a punctum. I do not like what is imposed on me, visually or otherwise, what prostitutes itself, what seeks to pass the superficial for the substantial.

BB: With your collection, you clearly pursue an encyclopedic goal. What is allegedly worthless continually tests the recognized. Do you want to correct the blind spots of your contemporaries?

PH: Forty-five years ago, by collecting the mundane, the everyday, I did what art has since accomplished by taking an interest in trash. I wanted to show that the mediocre can be captivating. Someone recently called it enlightening. I have always been interested in the modest, what is apparently ugly, overlooked. But, paradoxically, we can only draw attention to these photos by juxtaposing them to pearls, it allows us to see how great they are, in the end. I always wanted to avoid presenting only the icons.

BB: Does that mean that we have to ignore aesthetic prejudices?

PH: It’s a first thing. You should also always try to look at the photographs through the prism of the human, and not only with the glasses of the art historian, the sociologist, the historian. We have to see them as particles of a reality which is a part of our own reality. What kind of human being is there behind the picture, what kind of story? It doesn’t matter whether it’s an artist’s work or not. What is much more interesting is the reason why a snapshot is like this and not otherwise. This is the enigma of photography.

BB: The first photographs of daily life and the world of work were taken by people who had a particular sensitivity for these subjects or who were interested in them …

PH: Absolutely. In the 19th century, the worker – when represented – was photographed in a group in front of the factory door, seized and thought of as the property of the manager. This type of shot was intended for reports to management and shareholders.

BB: Photography therefore quickly became a means of control in the service of progress, which aroused real euphoria at the time …

PH: With these photographs, where new industrial conquests, machines and halls flooded with light appear, we almost find ourselves in the shoes of factory owners. It’s pure ideology.

Every corner of the factory is cleared of workers’ trash. They are relegated to the outside and treated not as individuals, but as a group. Like a machine. This imagery is instituted by the oldest and most important factory photo, a daguerreotype that shows the personnel of a watch factory in Saint-Imier, around 1850.

BB:What have you learned about photography over the past 45 years?

PH: The collection taken in its entirety represents a legacy: photography is proof, control, testimony that something is like this or like that. However, the only conclusion I have drawn from the millions of photos I have seen is this: you cannot capture the world with photography, or anything else. We have to learn to accept that it is elusive.

BB: Your collection may be dispersed in the future. What significance would its dissolution have for you?

PH: It would be the consequence of what photography taught me. This collection was designed to make a large impact. It was important to show it, to talk about it with other people. One thing I quickly understood is that photography is a great way to enter into conversation with the most diverse people, students and teachers, old people, young people, workers, billionaires. The enrichment that photography has given me on a human level is immense. I sometimes suspect that this is the real reason that led me to make this collection.

The collector or the artist is a fisherman: the bait is his photography, his composition, it has no other objective than that of getting us to communicate. So that we do not get lost in this ocean, in this world that our limited possibilities do not allow us to understand but in which we are not alone.

Jacques Rancière, Le Destin des images, Paris, 2003

- Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Paris, 1980

-

- Jacques Rancière, Le Destin des images, Paris, 2003

- Roland Barthes, La Chambre claire, Paris, 1980

Excerpts of « Mit dem Augen des Sammlers, Barbara Basting im Gespräch mit Peter Herzog », in : Der Körper der Photographie – Eine Welterzählung in Aufnahmen der Sammlung Herzog, Limmat Verlag, Zurich, 2005

After studying Germanic and Romane philology, and philosophy at Constance and Pairs, Barbara Basting was editor of the Swiss cultural magazine du (1989-1999) and then of Tages-Anzeiger (2001-2008), both located in Zurich. Freelance journalist for various media, she was also editor-in-chief at the Swiss radio DRS2/SRF2 Kultur (2009-2012). She has headed the Visual Arts department of the city of Zurich since 2013.

————————————-

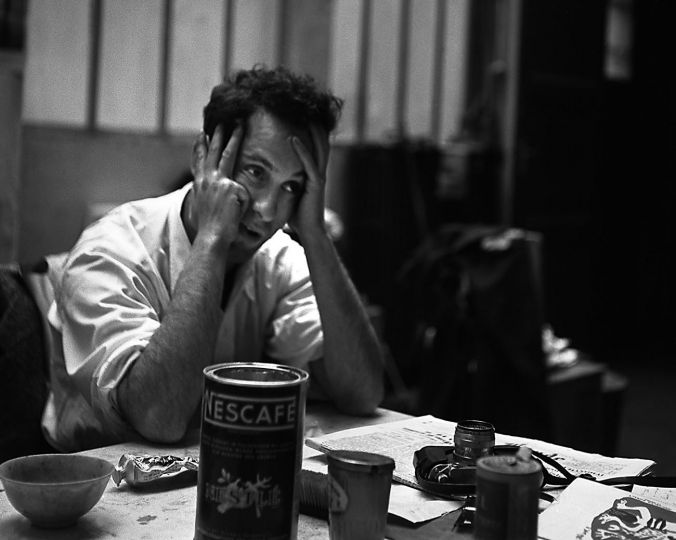

The thematic exhibition “… et labora” has its origins in the exploration of the collection of Ruth and Peter Herzog, which brings together more than 600,000 photographs – some anonymous, some from renowned practitioners. The hundreds of images presented here, combining pioneering photographs from the 19th century and photographs taken from the first half of the 20th century, question work in its representation and daily execution. The meeting of this selection with ex-votos from Provence and contemporary creation, capturing or enhancing different realities of workplaces, allows an exploration of this theme through multiple entrances.

Seizing the famous formula “Ora et labora” (“Pray and work”) linked to the lifestyle of Benedictine monks, the exhibition evokes by detour the withdrawal of the hand of God and spiritual work in favor of the invisible force of the market that has been constantly reorganizing our lives since the first industrial revolution.

The combined photographs orchestrate a panorama of the technological developments of the century that saw the birth of the advent of photography. They offer views of factories and major construction projects of the century linked, among other things, to the rapid growth of metropolitan areas – metros, tunnels and railway lines – or to the mechanization of agricultural work.

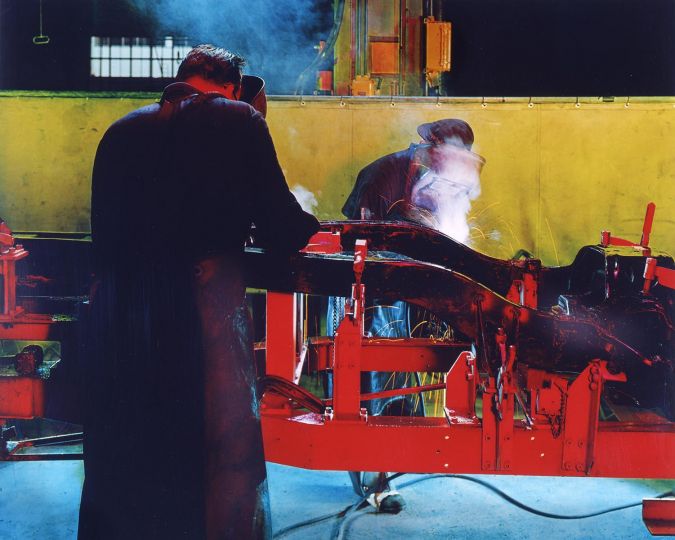

They also capture the fragile presence of the individual in these closed or changing environments.

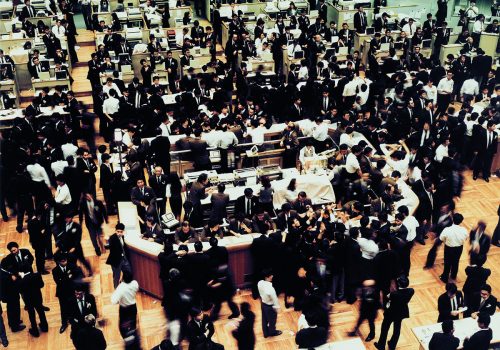

Through their large format works, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth conduct their own investigation of the current working world. Represented from an astonishing distance, the workplaces of a globalized and high-tech world are entering contemporary art.

The appearance of the human-cyborg, the exploitation of working-class minorities or the presence of street vendors are all subjects captured by the contemporary artists presented at the Foundation.

Another specific look linked to human activities is found in the Provencal votive offerings, born of a simple and direct gesture of faith in the 19th and 20th centuries, representing work accidents. By succeeding in depicting scenes that the photography of the time was not yet able to capture on the spot, these objects of popular art also reflect the secularization of mentalities, perceptible through their iconographic evolution.

With the development of industrial society, we are witnessing the appearance of new activities but also the profound transformation of socio-cultural categories.

The beginning of the 20th century thus saw the new proletarian class unionize; the demands brought by the workers will offer the possibility for the following generations to enjoy new social rights allowing them to go on vacation, to have fun, or to move more easily. These moments of leisure will continue to be documented thanks to the new medium of photography, which has become more democratic.

The dynamism experienced by Europe at the time goes hand in hand with a remarkable change in living spaces. Thanks to the rural exodus, cities abound in small trades, some representations of which have come down to us. It was also the era of the rise of the tertiary sector: the catering, service and communication professions prospered and passed, in the eyes of the youth of this first half of the 20th century, for trades of the future.

However, industrial development does not exclude the agricultural world – on the contrary, it is working on its intensive modernization and restructuring.

If the machine, ever more present, seems to be the strong symbol of this evolution, the human being, essential cog of production in the pre and post-industrial era, remains at the Heart of the implementation of these changes. His body is his first instrument, as evidenced by the film Incremental Self: transparent bodies (2017) by Emmanuelle Lainé on the interdependence between man and his prosthetic machine, but also all the anonymous photographs immortalizing manual workers posing at their workplace.

Today, the economic and technical materiality of late capitalism is fading away gradually in favor of a dematerialized and deterritorialized economy, the most successful form of which could be cryptocurrency. Yuri Pattison, with his work The Ideal (2015), reveals to us the rudimentary and eminently political aspect behind the development of the best known of them, bitcoin.

Exhibition curator: Bice Curiger

with Julia Marchand, assistant curator

and Margaux Bonopera, assistant curator

Editor’s note : The texts are extracted from the catalog to be published.

… et labora

exhibition from November 16, 2019 to April 13, 2020

A thematic exhibition with

photographs from the Ruth + Peter Herzog collection,

works by Cyprien Gaillard, Andreas Gursky,

Michael Hakimi, Emmanuelle Lainé,

Yuri Pattison, Mika Rottenberg,

Thomas Struth, Liu Xiaodong,

ex-voto from Provence

as well as the painting Chauve-souris (Bat) (1884) by de Vincent Van Gogh

exhibition curator: Bice Curiger

Fondation Vincent Van Gogh Arles

35ter rue du Docteur-Fanton

13200 Arles

www.fondation-vincentvangogh-arles.org