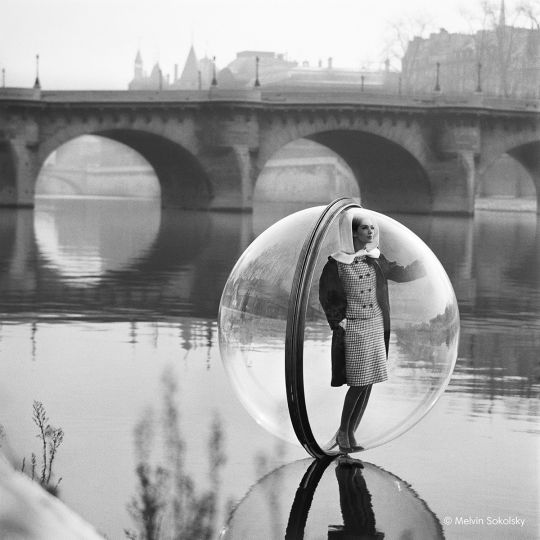

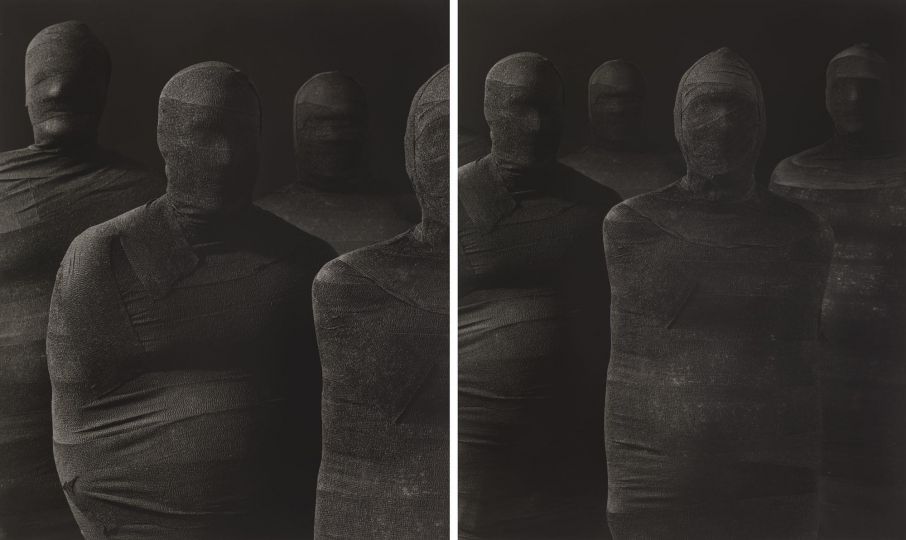

Synonymous with the art of travel since 1854, Louis Vuitton continues to add titles to its “Fashion Eye” collection. Each book evokes a city, region or country as seen through the eyes of a photographer. With this third book devoted to Paris, the collection returns to two iconic series by Melvin Sokolsky.

After Jean-Loup Sieff’s Paris, published among the first works of “Fashion Eye”, and the more recent and amusing look of Feng Li, the collection directed by Julien Guerrier reopens the “Melvin Sokolsky” dossier. Can we still look at these works, taken from the mythical series that became “Bubble” (1962) and “Fly” (1965), with fresh eyes? Is the wonder still there? Does the grace still work?

At the hearing, which would have expected a courtroom battle, a real trial for the prosecution, a litany of bad faith and low blows, nothing of the sort happened. It is a non-lieu, or rather, a book that exists, that stands out. The publisher is in good faith and the jury is convinced. Sixty years after their publication in Harper’s Bazaar, the magic still works.

Thanks are due in particular to the text by Alain-Paul Maillard. The critic brilliantly recontextualises the atmosphere of the time and the adventurous character of Melvin Sokolsky. In 1962, the young American photographer was still a hothead, an autodidact with radical and divisive ideas.

He joined the cohort of photographers at Harper’s Bazaar. He joined the magazine in 1959 at the invitation of the new artistic director Henry Wolf and worked alongside the indestructible Richard Avedon and Lillian Bassman, and the equally newly invited Saul Leiter.

Like Leiter, his eye brings freshness and new ideas. But Sokolsky also encounters opposition to his projects, which are deemed unfeasible and costly. He has to fight and defend his choices, especially the models in his series. His photographs were judged strange, and he was refused certain works out of snobbery, such as a series photographed in the metro (“Because the management did not see its subscribers taking the metro”).

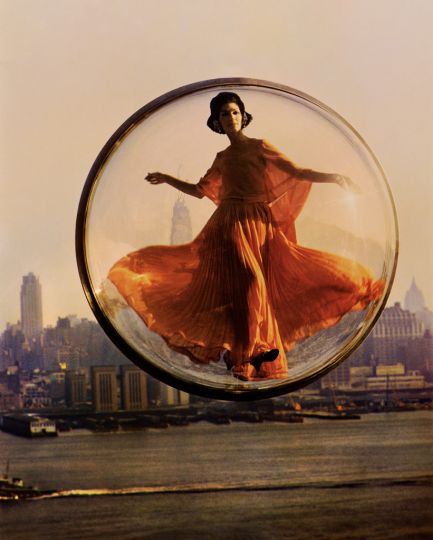

However, Sokolsky had the absolute confidence of the artistic director: “He was only interested in my personal and artistic vision. The main thing was that people looked at my work and said – this is a Sokolsky,” he recalls. The “Bubble” series is an example of this.

It is entirely based on the lightness of a bubble, the subtle, airy poses of the model trapped inside it and an equally elegant imagery of Paris. The success of the shoot rests as much on Simone d’Aillencourt’s natural performance as on the technical and material aspects of the shoot.

In an interview published in our pages, Sokolky recalls her lightness. “Simone was more comfortable in the bubble than if she were the pilot of a spaceship. In this she contrasted with models who were surprised by the bubble being lifted from the ground, and were awkward, scared or just bad actors.

The shoot in Paris proved more complicated to manage. Moving and flying the bubble and its model proved to be time consuming and tedious. Each new shot in Paris required the crane to travel for a good hour. Onlookers crowded around, admired, called out… And the team at Sokolsky’s side was limited to that of his studio, five to seven people at the most. “If you tried to make the 1963 Paris Bubble, it would cost hundreds of thousands of dollars today; not to mention the exorbitant cost of insurance.

The success of ‘Bubble’ also lies in the Parisian setting. While Paris was already widely featured in photography and film in the early 1960s, American fashion photography confined its representation to its great monuments. Sokolsky was keen to show an intimate as well as elegant version of it and used the Parisian winter light which, whatever the grey moods of the sky, it remains magnificent when punctured by timid rays.

“I would venture to say that the success of an image is based on the harmony between the idea and the lighting. There is a right light for everything,” the artist told the Izzy Gallery. And the unvarnished, unprojected light of Paris was enough for him. The sky added to the surreal atmosphere, inspired by discussions with Dali, in line with his personal research and fascinations.

Two years later, in 1965, the model Dorothy McGowan burst the bubble and found herself suspended in a special corset, supported by rings and woven with steel cables, in the air. It was the equally mythical ‘Fly’ series. “There’s nothing Melvin could not do when he had an idea,” said McGowan.

There remains a question, and if one may say so, the question: why do we think these two series iconic? What does the viewer find in these images? Perhaps the answer comes from their joy, from this immense joy that draws on lightness, dance, grace… Like a leitmotif in Sokolsky’s work, perhaps judged with disdain today, at a time when it is necessary to dare, shock and break with the norm…

“When I think about my life as a photographer, the most important desire I have is to create images that give the viewer a sense of hope and joy. I want the viewer to look at my photographs and feel good. Just think about waking up and looking at one of my pictures, and it sets you up for a great day,” the artist told Mario Lopez Pisani.

Melvin Sokolsky – Paris

Éditions Louis Vuitton, 2021

Fashion Eye” collection, edited by Julien Guerrier

Edited by Michel Mallard

Graphic design by Lords of Design

Bilingual French-English, 96 pages.

Available in bookshops or online