Impalas, lycaons et autres paysages is the name of Dune Varela’s new book, published by Lutanie. Manon Lutanie, the director of the collection, sat down to speak with the author:

Manon Lutanie : How did you get the idea for this series of photographs ?

Dune Varela : One day, I visited the San José Natural History Museum in Costa Rica. The museum is on the outskirts of the city, completely isolated, in the middle of nowhere. It houses a collection of antiquated stuffed animals that are arranged in re-created natural settings, called dioramas. I wanted to create a series based on these dioramas. A naturalistic diorama is like a photograph : both a reproduction and a fragment of reality. It’s a scenographic creation that also seeks to surpass this reality by creating its own representation of the world. It’s strange that it should be Louis Daguerre, the inventor of the daguerreotype, who also developed the diorama. Originally, the diorama was a panoramic painting used in theatre, illuminated in such a way that the spectator had the illusion of seeing a real landscape. Diorama literally means “to see through”. In a naturalistic diorama, there is the notion of identifying animal species, of informing in a scientific way – just like photography in its early stages. Dioramas are also a way of putting a frame onto nature. I wanted to create a mise en abyme through the photographic image, which in itself is the delimitation of a visual field. I also wanted to work on landscape. And this kind of aestheticization of nature within a museum appealed to me.

Did you know right from the start that you would associate these photographs, taken indoors, with photographs taken in a natural setting ?

My work is a constant flow between what is thought out and conceptualized, and what I perceive intuitively. I always start with an image and build upon it. I try to establish connections. It was seeing a diorama that led me to develop a story on the artificialization of nature. In this series, the choice of images has more to do with analogy than harmony. Associating “real” landscapes with photographs of naturalistic scenes was also a way to question the representation of reality. The idea was to play on different degrees of perception. I like to blur the edges between natural and artificial, real and fictional. I seek out that space where the reality of the photographed object, as well as the image itself, becomes uncertain : is it a set, a real landscape, or a painting ? Landscape, in contemporary photography, mainly focuses on peri-urban zones. I wanted to take a different approach. What interests me is the theatricalization through which humankind repossesses Nature, and in particular the reconstruction of wilderness zones within closed spaces for scientific or cultural purposes. When I photograph dioramas, I’m recording landscapes that are constructed and immobile. They are sets, archetypal images of nature. Associating them with real landscapes allows me to extricate them from their frames, to make them exist in a different way.

When one of the photographs was exhibited at the Maison européene de la photographie a few months ago, you told me that someone, upon learning that you were the artist, said that it resembled you.

Maybe because I look like an animal : freckle-spotted like a leopard, giraffe-like colouring… And because I spent my childhood across from the Jardin des Plantes. I used to sneak into the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution, which was closed for years and forbidden to the public. My neighbour Armin and I had found a secret entrance through the right wing of the building. This huge space, plunged in darkness, housed a large collection of taxidermied animals. We had a ritual of exploring the “forbidden gallery”, on tiptoe and holding flashlights, slipping in and out of the stuffed animals’ frightening shadows.

There’s a sadness in this pursuit of beauty, and a kind of longing to capture what is pure and might soon vanish ( certain animal species, certain protected landscapes, childhood ). This sadness is heightened by the fact that the dioramas themselves are an idealized ( more than scientific, sometimes ) replica of nature, don’t you think ?

In the beginning, I wanted to call this series “Paradises lost”. But that title seemed full of nostalgia, and that’s not what these pictures are about. There’s no doubt something here that touches on disenchantment and escape. And perhaps a feeling of sadness, of absence.

The thing that places these photographs in the modern world – more so than the dioramas, which themselves are quite ancient – is a tiny detail : the blue plastic sandals. I find this detail to be absolutely fundamental in the book, because on its own, it demolishes anything nostalgic about your approach. With this little stroke of blue, we understand that we’ve left the state of nature and that the idea isn’t to re-create its exact replica.

My pictures are staged but I enjoy accidents, like those blue plastic sandals he wanted to keep on – a detail that seems like a mistake, but in the end makes the picture anachronistic or contemporary, depending on the point of view you choose. I work in silver print, and that implies an element of uncertainty, of mystery, every time the shutter clicks. And there’s tension while waiting to see what the negative will reveal.

This series is a bit like a bestiary, but an ancient, mythical bestiary. It’s obviously not about making an inventory of the most common animals. Apart from the leopards, the lion and the wolf, the animals photographed are not immediately identifiable for most people. Moreover, the lion isn’t represented in the usual way : it seems starving and solitary. While we were working on the choice of pictures, you decided not to include a photograph of a family of brown bears – even though it was an excellent shot – because there was something friendly about them.

What’s the meaning behind your choice of animals, and did you look for any particular “expressions” in them ?

I like it that some animals are strange and not recognizable. I wanted to avoid the “Walt Disney”, idealized image. With photography, I often seek out the moment where everything seems to be suspended, caught between two states – the moment before

everything changes. It’s true that with taxidermied animals, there’s an opposition between the animal’s real death and the aesthetic desire to make it seem alive. The feeling of suspension is heightened by the taxidermied animal’s own stillness, which creates an unsettling temporality.

It’s strange, because what we don’t actually see in the book, although we realize it must be so, is that the animals are filled with straw – filled with the landscape, in fact. I’m very aware of this every time I look at the images : the omnipresence of the plant world, even inside the animals’ bodies.

The first time I touched a taxidermied animal was after the Deyrolle fire. I had to photograph certain animals and move a half-charred zebra. When I touched it, I felt such repulsion that I couldn’t move it, as if the fact that it had been burned made it really dead. All I could see was the hurt, wounded animal. In the end, I photographed a Deyrolle room that had no animals, the laboratory, which in fact looks like the storeroom of a natural history museum. I didn’t sense death in this way with the dio-ramas. Arranged as living paintings, the animals looked like land-scapes to me, and it never struck me that they were full of straw. The animals had moved beyond a simple “still-life” and become a landscape.

Does the series come to a close with this book ?

This series is finished but I will continue to photograph dioramas in other natural history museums, because I won’t be able to help it !

What are you working on currently ?

At the moment, I’m working on several series. I’m still exploring the artificialization and framing of nature through the re-creation of natural settings in zoos, botanical gardens and dinosaur parks. I’ve also begun a series of portraits of children who are barely visible, hidden behind bushes, leaves or trees. The idea came to me one day as I was walking in a zoo : I peered into the shadows behind some bushes and found myself looking deeply into a kangaroo’s eyes. There was something very beautiful in the animal’s gaze – a fragility and a magical strength. There are moments that photography cannot and must not record, but that it later attempts to re-create.

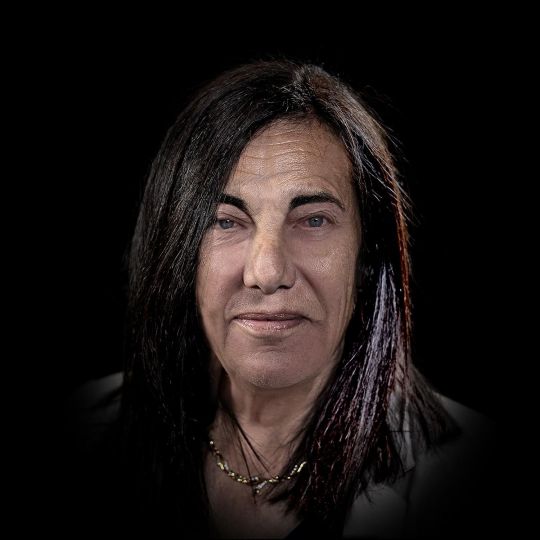

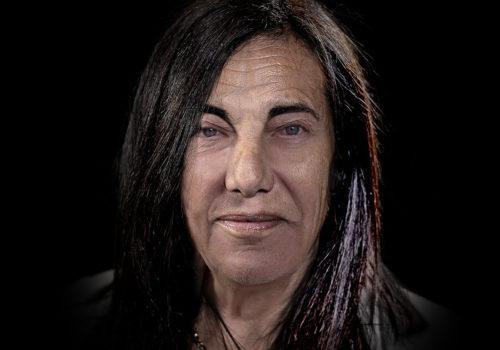

Impalas, lycaons, Dune Varela

Editions Lutanie, 2012

20 x 14 cm, 72 pages

ISBN : 978-2-918685-03-6