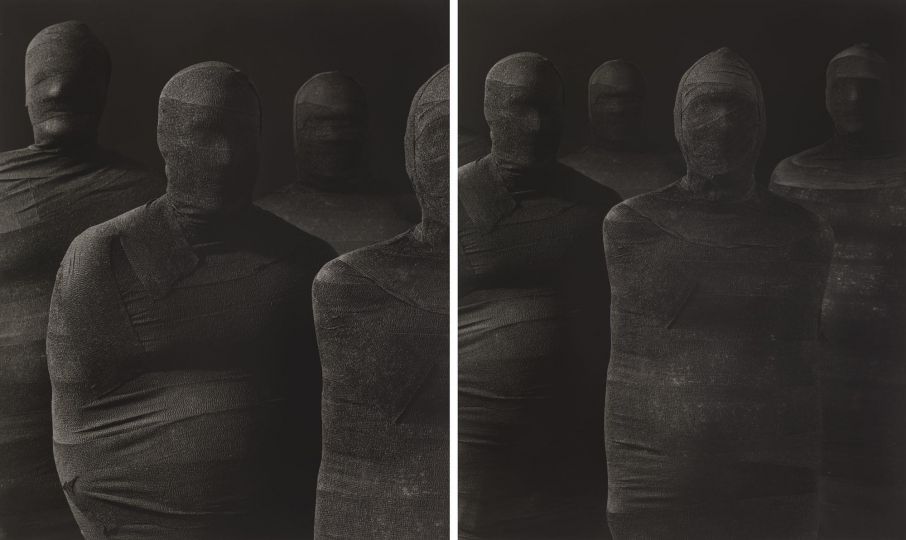

With its gilt edges, hardbound cover, and a stylized illustration of the indigenous world, The Jungle Book appears at first glance to be a reprint of Rudyard Kipling’s stories. While it is indeed a collection of stories, these stories are about a demystified Amazonia; they are about an “hallucinatory jungle,” to borrow the words with which Arnaud Robert concludes his beautiful introduction.

The photographer Yann Gross paints a picture of this mythical forest that shies away from exoticism. Instead, we savor the paradoxes of reciprocal stereotypes and acculturation. Scattered throughout the book and interspersed with images, concise anecdotes, set in font size 18 , give voice to the local inhabitants, for better or for worse. We encounter a schoolteacher named Hitler and a baby baptized Ampicilina, after the only antibiotic prescribed by traveling clinics. Read with a Westerner’s eye, these vignettes make one smile, even if, as the photographer tells us, “the navy disburses medication without making a diagnosis, which wreaks havoc on the metabolism of these people.”

The words of a native Suruí (Brazil) offer the flipside of the story: “We have never had any problems with consanguinity. There are no people with the Down syndrome or homosexuals among our nation. These are white man’s illnesses,” he said. His analysis — that of a biologist, as we learn from a note at the end of the book — follows a traditional Suruí explanation: “The Suruí people are polygamous. A man must marry the daughter of his sister, his niece.”

“What I found interesting was trying to stay clear of exotic stereotypes. I also wanted to invoke the desire to be a part of the globalized world by repeating all these absurdities pandered since the conquest,” Yann Gross explained. His interest in the subject can be traced back to 2008, when he worked as a civil servant on a reforestation project in northeastern Brazil. He discovered then that few people spoke their native language; that they drank, played soccer, and dressed up Saturday nights to go dancing in the village square. Their attention to appearances went so far as to refuse to let him come along with his unkempt beard and rugged outfit.

While the texts are written in a style inspired by children’s stories, they demonstrate an utmost lexical rigor. “I was interested in the idea of being ‘civilized’,” Yann Gross went on to say. “One often imagines an indigenous culture as being frozen in time, but this culture evolves like any other, without, however, losing its roots.” Yet there are some exceptions. The book reveals that children have lost the ability to tell each other stories around the fire because the TV screen fills up their nights, and that a shaman turned church doorman has willingly abandoned his culture and traditional lore.

“The argument of this indigenous chief was that, despite acculturation, one takes what’s good about technology. But that’s not really the case in real life; much of the culture is becoming extinct. And this is where, for me, things get complicated,” added Yann Gross. “The same is true of the exploitation of natural resources. There are many who fight against oil extraction, gold mining, dam construction, and intensive farming, but they are only a fraction of the population of the Amazon River Basin. Others go along with it for the sake of creature comforts offered by the sudden windfall. This is about the little things. They don’t dream about becoming rich, just middle-of-the-road.” And when they’re left with nothing, when their forest has been razed, transformed into a no-man’s land, they fight to recover the territory where their forefathers are buried, and they are ready to die for it or live as refugees on their own land.

There is a common, geographic, thread running through this book, which retraces Francisco de Orellana’s voyage down the Amazon River — an expedition that had shifted the dynamics in the Americas. It necessarily ends on a tragic note. Landing at the foot of the Andes, near San Rafael Falls, in Ecuador, de Orellana gradually made his way through the forest until he reached the waterway. “We leave behind the river and the forest with their mysteries and their myths. The farther we get, the more room there is for the imagination, for a certain freedom and for a tragicomic absurd.” And thus, in the middle of the book, printed on a different quality paper, we find a witty inventory of the most popular market in the Peruvian Amazon region: all sorts of animals, herbs, and magic charms, either traditional or invented for the sole of purpose of making money. “But in the end, what I wanted to get across was the fact that while there are still indigenous people, the forest is gone,” concluded Yann Gross.

As Werner Herzog wrote to him: “It goes beyond the feverish dream that spans across the Amazon region. Looking at this book, it seems that this whole landscape, from one end to the other, is under a spell.”

Laurence Cornet

Yann Gross,The Jungle Book

Published by ActesSud and Aperture

€ 29 / $ 30

http://yanngross.com/

http://www.actes-sud.fr/

http://aperture.org/