Erich Hartmann (1922 -1999)

Renowned for his photographic interpretation of the arts, the industrial landscape and the beauties of technology, Erich Hartmann spent a lifetime as a photojournalist, leaving a large and varied body of work. Invited in 1951 to join Magnum Photos, the international cooperative of free-lance photojournalists founded in 1947 by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, David Seymour and George Rodger, Erich was for many years on its Board of Directors and served as Vice-President and President.

Born in Germany, he spent his childhood in the beautiful town of Passau on the Danube. As the Nazi threat rose in the 1930’s the family fled to what they thought would be the anonymity of the larger city of Munich, believing that the political madness would pass. However, there was no hiding and they were saved from the fate of most of German and European Jewry by an affidavit from a distant relative allowing them to emigrate to the United States. Erich was then just sixteen and was for some time the sole support of his family in the United States as he was the only one of the five (parents and three children) then fluent in English. When the United States entered the Second World War he volunteered for the U.S. Army and spent the war years on the battlefields of Europe, landing in Normandy and fighting across France and Belgium, barely surviving the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes Forest. At the cessation of hostilities in Europe he was posted to Cologne, Germany, as an interpreter in the military courts.

On his release from war service he came to New York City where we met at the house of mutual friends and soon married. He found work as assistant to a portrait photographer working often at the fledgling United Nations and I was a book editor in a publishing house. By the time he became associated with Magnum he was already a free lance, first taking authors’ portraits for publishers, then working on varied magazine assignments. His early color portfolios of science and industry (“The Deep North” and “The Saint Lawrence Seaway”, among others) for Fortune magazine showed his uniquely artistic approach.

He is credited by his peers with being the first to bring a photojournalistic technique and an artist’s eye to corporate photography, thereby opening a new field for photojournalists whose main outlets theretofore had been magazines and newspapers. For IBM, Boeing, RCA, Kimberly Clark, Ford Motors and many other companies in the US and Europe he photographed, principally in color, their personnel, their factories, their raw materials and the landscapes in which all were situated. Throughout his career he brought the same dedicated professionalism to these corporate assignments as to editorial work , thus finding both equally fulfilling.

In the 1960’s, by which time we had two young children, we lived for several years in London where Erich’s color photo essays, notably “Shakespeare’s Warwickshire”, “Thomas Hardy’s Wessex” , “Thomas Mann’s Venice” , “Styles of English Architecture” appeared regularly in the leading Sunday Magazine Supplements. During that time also he photographed the Dublin wanderings of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and followed a lifelong interest in aviation with an eloquent black and white documentation of the construction of the Britannia Aircraft for the Bristol Aeroplane Company.

His wide-ranging interests included portraits of writers, architects, politicians; extensive coverage of music and art including color essays on the French mime Marcel Marceau, music festivals in Salzburg and in Lockenhaus, studies of string quartets, soloists, conductors and composers as well as news stories from Argentina to Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia), from Alaska to Tehran. His work in science and industry, photographing the Max Planck Societies, “Quarks”, Genetics Labs, the European Space Program and widespread experimental work at IBM deepened his fascination with the beauty of the components of technology. A former Bureau Chief of Magnum described him as “A man of great intellect who recognized the artistic beauty of technology before anyone else, a combined interest in technology and humanity.”

He knew that the age of mechanical technology had run its course and was being replaced by an electronic age that extended man’s mental functions as the mechanical age had once extended his physical abilities. He saw it as a world where smaller is better because the smaller the component the shorter its electrical path and the faster it works. Bringing his private perceptions to the consideration of technology, he saw in its intricacies, at close range, forms that reminded him of sculpture, painting and architecture, ancient and modern, suggesting that functional form is always pleasing to the eye. He rarely referred to such components and images as “beautiful”, a word he rejected in favor of “powerful” or “expressive”. His photographs of these tiny components of electronics were usually taken on our dining-room table, his “studio” consisting of a cardboard box. He said, “Something that you might find in nature, a leaf or the shell of a nautilus, has a meaning far greater than the photogenic. Its purpose is to make possible, to perpetuate, to contain a form of life. So it is with these things at the heart of technology.” He found that revelation to a degree comforting, because as long as there is human creativity at the heart of both works of art and the products of technology he thought that there was reason to believe that technology would retain its place as a tool of human endeavor and not its depersonalized master.

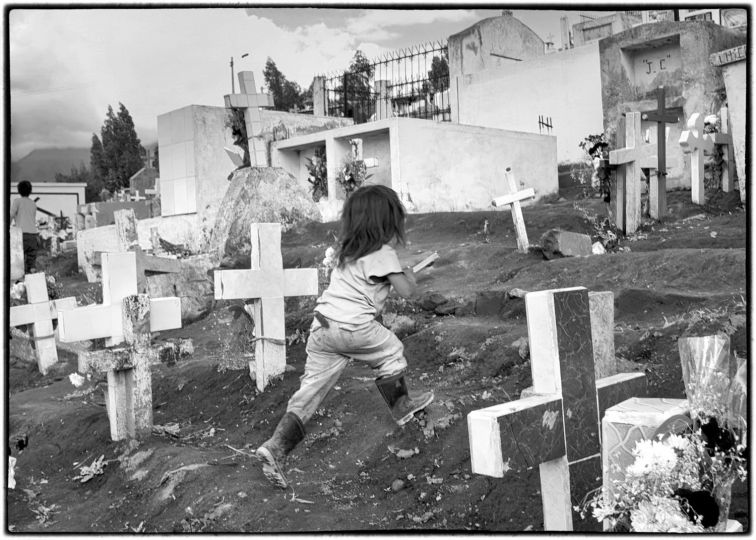

Throughout the fifty-odd years of his working life, together with his assignments, there were his personal pictures which fill a fat book of contact sheets for each year. He was never without a camera and saw pictures everywhere. There are hundreds of pictures of me and our children, Nicholas and Celia, who became accustomed to being photographed from their earliest days. Erich also loved to print, introducing Nicholas at a young age to the mysteries of the darkroom to watch a picture magically appear in a tray of liquid. On a vacation trip around France Erich carried an early “Point and Shoot” camera in his shirt pocket. Those personal holiday pictures became an exhibit, “Train Journey”, which was shown in numerous places and excerpted in publications in Europe and the United States. After Erich’s death I made a selection from his years of personal pictures for a book entitled “Where I Was” which was published in Austria in 2000 with an accompanying exhibit that has been shown in Germany, Austria, the U.S. and Japan.

In addition to his assignments, which involved extensive travelling on every continent except Antarctica, and his almost daily “personal pictures” were his private obsessions, such as his self-assigned project “Our Daily Bread” which resulted in a major exhibition in l962 and eventually in 2013 a book. Other obsessions arose from curiosity about the photographic possibilities of chance encounters such as his discovery of a mannequin factory in New York City. There he photographed the figures and parts of figures as he found them on the factory floor and put the photographs together in an exhibition that reviewers found “disquieting and moving”. He was captivated by the name, “Mannequin Factory”, a massing of identical bodies suggestive of the impersonality and anonymity of aspects of modern life, as a mirror of our time . One reviewer at the time found in the photographs echoes of the Nazi Camps and of an Orwellian dictatorship inhabited by impersonal automatons. Years later Erich photographed for a German magazine an extended color essay titled “1984”. One can see there his continuing concern with the alienation of the times; “Alienation” had been in fact the title of one of his early magazine essays. Yet another reviewer wrote that the photograph of the box of arms “suggests Buchenwald”. That similarity reveals Erich’s long personal struggle with the subject and meaning of the Nazi concentration camps as the terrifying end of a national policy of dehumanization.

Towards the end of his life he documented the remains of the those concentration and death camps on a winter journey that we both undertook through Germany, Austria, France, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The resulting book “In the Camps” was published in 1995 in the U.S., England, France, Germany and Italy; the exhibition of the photographs has been shown in more than twenty venues in the U. S. and Europe.

One subject he did not choose to photograph is war, although he did go to Viet Nam during those war years. His mission, however, was as the photographer accompanying a delegation of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a group dedicated to efforts to resolve that conflict.

Once upon a time in a camera repair shop in Manhattan there was a wizard named Marty Forscher. Every day busy and famous photographers sat patiently on a bench outside his workshop-office awaiting their turn to show him their ailing cameras in the certain belief that Marty could reverse the damage of drops, dampness, age, or the general recalcitrance of things.

Erich Hartmann loved gadgets and it was to Marty Forscher that he would go when he had an idea for the modification of a camera that would enable him to produce an image or an effect that he wanted. He would sketch out his idea, and Marty would make it real. Erich’s aim was to make the camera see what he saw – he was not interested in after-the-fact darkroom manipulation. With his ideas and Marty’s genius Erich was able to take the panoramic pictures he wanted before the panoramic camera came onto the market. Through the magic of something he called his “Timing Modulator” he was able to capture motion and speed, notably in his coverage of the Monte Carlo car races. Another camera modification was a multiple exposure shutter of his own invention that could make as many as eight exposures in a single frame. “Figures and shadows overlap without losing identity”, he said. “I’ve tried to get beyond mass, form and texture, those familiar elements of photography, into a fourth dimension, time.” A famous example of that technique was a two-page color photograph of commuters in Grand Central Station published in Life Magazine in 1969, witness to this early experimentation.

His obsession with the possibilities of incorporating laser light into his photographs occupied him for a number of years and was worked on between assignments, often in our New York apartment or on summer family holidays in Maine as he tried to achieve a new form, perhaps a new language of expression. By the time he had solved some of the problems he had set for himself and was pleased with the result, he wrote, in the text panel for the New York exhibit of the photographs entitled “A Play of Light” , “These photographs give me a sense of satisfaction because I have been able to use familiar, sometimes commonplace situations and, by the introduction of an unfamiliar way of using light, transform them into images which seem to me disquieting, questioning, ambiguous”.

He was a lifelong recorder of the world of work and a believer in the urgent need for human connection. In the Afterword of his book “In the Camps” he wrote, “Except perhaps in dreams, life no longer takes place on a solitary plane; it is now irrevocably complex and we, whoever we are, have become intertwined one with another whether we like it or not.”

His first solo exhibit, at the Museum of the City of New York in 1956, consisted of twenty-five photographs of and around Brooklyn Bridge. His last magazine assignment, published posthumously in 1999 in the German Magazine FOCUS, was a color portfolio of the Bridges of Manhattan. He had come full circle, after a lifetime of travel photographing a wide variety of human endeavor, to record once more the architectural beauty and symbolism of the spans that connect the island of Manhattan, his adopted home, with the rest of the world.

© Ruth Bains Hartmann, 2013