Francisco Medail – Photographies 1930-1943 is a hypothesis or a historiographic provocation. Medail’s visual essay plays with the possibility of rewriting a page in the history of Argentine photography. While local artistic historiography of the 1930´s hoisted the modern proposals of Coppola, Stern, Saderman, Heinrich, and the more conservative debtors of the aesthetics of photoclubism, it neglected public and private photographs that ran through other channels, with uses and operations outside the field of art. These form an immense iconographic corpus in which historians, editors, journalists, essayists are eventually immersed in search of visual documents of the past.

Francisco Medail’s proposal involves crossing both spheres and carrying out an aesthetic search on most heterogeneous sets of photographs, as they were frequently formed with images from different sources -institutional, journalistic, amateur-, generated for different purposes. Thus, what this show puts on the scene is, in short, the old discussion art versus document, updated to the age of appropriations.

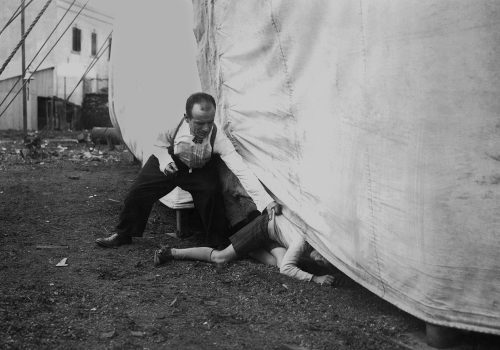

By placing the focus on the aesthetic, the external conditions of the photographic practice were voluntarily diluted (contractual situation or original intentions of the photographers, which, on the other hand, we could not know given the effacement of the names in most cases). Instead, the search was focused on the forms that are paired with the ways of production: quick shots of scenes or of events also fleeting and incidental or occurred between the tumult and agitation. Thus, Medail brings forth an aesthetic rooted in the variables of the photographic language itself: moved images, out of focus, seemingly unsuccessful frames, shots captured in passing.

Similar operations were carried out by researchers and curators from different parts of the world in the realm of the so-called vernacular photography (i.e. amateur and unknown author whose production of documentary-affective intention and without artistic pretensions was circumscribed to the private sphere), seeking in the result of a random capture, the value of an aesthetic decision. It’s not difficult to see the risk of such interventions and to notice the labile limit between discovery and invention.

In an already famous essay[1], American art critic Rosalind Krauss reproached Peter Galassi, curator of MoMA photography and responsible for the Before Photography[2] show, for having imposed categories from the art field to archival photography produced in other contexts and with extra-artistic purposes, with the objective of validating and valuing them for the museum. Galassi had made an acute reading on nineteenth-century photography and its relation to painting immediately prior to its invention, and in the catalog text he pointed out the compositional characteristics that related them and declared photography a “legitimate daughter” of the Western pictorial tradition. In his perspective of alla Wölfflin, what he put aside, motivating Krauss’s criticism, were the contexts of production and the spaces of circulation and diffusion. These are, we know, fundamental and constituent factors of archives. That is why I say that Medail’s proposal is a historiographic provocation.

But it is in stylistic rather than documentary terms, since the exhibition builds a possible chronicle of Buenos Aires in the 1930s. Each picture unfolds a story. They are, for the most part, scenes of life on the streets and in public places. The political and proselytizing activity appears as a theme and also as substrate of the urban pulse that we see in the other images: food, industry, transport, leisure and business are the analytical cuts of some days anodyne and other exceptional. Historical events are combined with daily records to build a mosaic on the period of delivery, corruption and fraud that began in 1930 with the first civic-military coup of the century in Argentina. But, at the same time, the construction of this iconographic corpus of the Infamous Decade was guided by the search for certain aesthetic qualities and brings to light an internal compositional coherence, a possible style of author or period that, however, we know apocryphal. Note that it’s not in Medail to build a plausible fiction, in the style of Joan Fontcuberta in Sputnik[3], but to propose a way of seeing. Thus, his essay points to the apocryphal and the anachronistic simultaneously. The thick grains, the off-center frames, the flou, the circumstantial scene, are certain characteristics of the quick and random capture we see in these images and that Robert Frank would turn into his personal style to document the North American life of the mid-twentieth century, style sealed with the appearance of his book The Americans[4]. Because Walkers Evans and, even more, Frank will be the referents for this aesthetic that Buenos Aires photographs of the ’30s would be foretelling.

In suggesting the possibility of encountering a Frank avant la lettre, with a Hercules Florence in the middle of the political jungle of patriotic fraud, the history of photography and the history of the country are intricately undiscernible. Thus, we can understand this sort of updating of the gaze – seeing historical photographs with contemporary eyes – also as a form of political analogy between yesterday and today, as a certain ideological substance of the Conservative Restoration is renewed in these days.

In this sense, it is noteworthy that this is the first work in which Medail is introduced in historical archives to interrogate contexts, forms and senses, proposing the time variable for the re-contextualization of the images. Thus, the transfer of intimate photographs 2.0 to the gallery wall was put at stake and in Implosion the materiality of the image was questioned, here the context changes in two ways: from the archive to the exhibition space and from the past to the present. The operation we already saw in Part – where the photographs of drug traffickers published by themselves on social media were copied in silver gelatin, – are now done on historical materials. That is to say, Part implied the transposition of a contemporary image to an earlier language based on its materiality, while the current proposal, on the other hand, consists in bringing contemporary images of the past based on their compositional language. Hence, Francisco Medail – Photographs 1930-1943 defies the idea of author and chronology, and at the same time, he makes a reference to the titles of the books published by the Antorchas Foundation in the 1990s, fundamental in the historiography of Argentine photography.

Veronica Tell

Veronica Tell is an author and curator in photography.

Francisco Medail, Photographs 1930 – 1943

From August 1 to September 29, 2017

Rolf Art.

Esmeralda 1353

Buenos Aires

Argentina

http://rolfart.com.ar/

[1] Rosalind Krauss. “Photography’s Discursive Spaces”, in: The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1985.

[2] Before Photography, Painting and the Invention of Photography. The Museum of Modern Art. Mayo-julio de 1981.

[3] Joan Fontcuberta, Sputnik, Madrid, Fundación Arte y Tecnología, 1997.

[4] Primera edición: Les Américains, Paris, Delpire Éditeur, 1958.