Valery Giscard d’Estaing visits China October 1980

To discover today the images of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing’s China state visit, dating almost to the day to 40 years ago, captured by the scrutinizing eye of Francis Latreille (at the time a reporter for France Soir), it is like seeing the past reappear, an era that we have forgotten, of renewal, of vitality, of hope, both in the French President’s deliberate and confident stride, and in the street scenes with the schoolgirls in Beijing and the university students in Shanghai, a reflection of 1980s’ China, on the way to reform and opening.

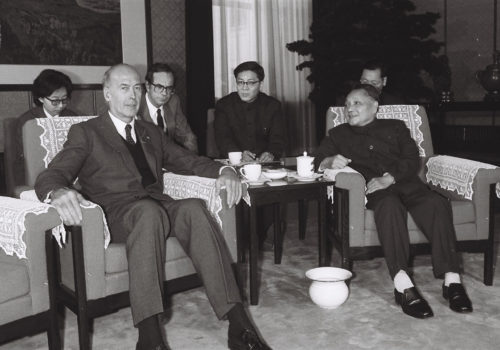

Towards the end of his seven-year term (which he did not know would be his only and last term), marked by economic crisis and political tensions in France, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing began his visit to China from October 15 to 22, 1980, seven years and one month after his predecessor Georges Pompidou. The second French head of state on official visit, he came at a key moment in China’s transformation. He would be received in Beijing by a team of Chinese leaders themselves in turmoil four years after the Cultural Revolution, ie; after Mao’s death. In Beijing he was greeted by the newly appointed Prime Minister Zhao Ziyang (1919-2005), a reformer of the post-Mao years alongside Hu Yaobang (1915-1989) the Chairman of the CCP. Hu Yaobang upon his death would spark the Tiananmen protests, and Zhao himself would become the tragic figure of the dramatic epilogue of the Tiananmen Revolt. His famous words uttered among the hunger strike students: “We’ve come too late, sorry” would earn him banishment and confinement under house arrest until the end of his life. Photo-reporter Francis Latreille photographed him in all his interactions with Giscard, with his glasses on and without glasses, reading his official speeches, signing bilateral agreements, engaged in “chopsticks dialogue” with the French president, he was fully on the path to his rise to power.

As the Chinese saw in Giscard a friend of China, confirmed by Charles de Gaulle’s official recognition in 1964, and by Pompidou as the first Western head of state to visit China in 1973, the French President found himself taken to tour the labyrinth of the opaque nebula of the Communist China’s Party-State dual system and meet up with its highest-ranking apparatchiks.

He was first received by Hua Guofeng (1921-2008), the designated successor (by the Gang of Four) of Mao, officially the Supreme Leader of the CCP, a pale figure, already weakened by Deng Xiaoping’s schemes to topple him, he would vanish from the scene by 1981. Hua Guofeng however in 1979 was welcomed at the Elysee Palace, a station in his tour of Western countries (unprecedented in Maoist annals) which saw him excel especially in banquet toasts under crystal candelabra and golden splendors, notably at Queen Elisabeth’s Buckingham Palace and… in Tehran with the Shah of Iran! It was a gift from Deng Xiaoping who sent him away so that he could quietly prepare his visit to President Jimmy Carter and launch a punitive war against Vietnam (to force the Vietnamese to withdraw their army occupying Cambodia and to repair the affront of having their protégé the Khmer Rouge driven out without Beijing’s consent). Then Giscard was taken to see Zhou Enlai’s widow, Madame Deng Yingchao (1904-1992), the Chairwoman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a symbolic position in the tradition created by Mao in placing at least one woman in the upper instances, starting with Sun Yat-sen’s widow, Madame Soong Ching-ling (1893-1981) who was vice-president of the People’s Republic. What could they have said to each other, when Anne-Aymone the French first lady was not even present?

These sessions provide us with the opportunity, however, to study and compare the furnishings and decorations of the reception rooms of these high personalities of the CCP. For example, here between Zhou Enlai’s widow and the French President there are a pack of cigarettes and a box of matches on the small table, but not the spittoon, a sign that Madame Zhou Enlai was a non-smoker. The spittoon, on the other hand, was prominently present at Deng Xiaoping, shining bright in white ceramic between Giscard and Deng, although ostensibly pushed closer to the side of the Chinese supreme leader. This spittoon should be a sort of “stigma” in the representations of all of Deng’s conversations with top foreign visitors, from Margaret Thatcher (1982) to Ronald Reagan (1984). One might always wonder if the fuss of throat-clearing and then spitting into the pot is not part of a scheme to destabilize the interlocutor in a negotiation. In Francis Latreille’s photo, we could see a visibly uncomfortable Giscard, as if he were wondering “will he ask me to spit in the pot too? “. This public display of spitting would require three major national campaigns and heavy fines to phase out progressively in Beijing with the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2008 Olympic Games and in Shanghai with the 2010 World Expo.

Then we could see Giscard recover a relaxed and delighted expression during the visit to the Forbidden City, followed by a veritable coterie of loyalists who have now all gone: Jean François-Poncet (1928-2012) Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alain Peyrefitte (1925 -1999) Minister of Justice, Jean-François Deniau (1928-2007), Minister of administrative reforms, a former Minister of Foreign Trade who, in this capacity, had prepared the visit, Jean Lecanuet (1920-1993) leader of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee and Pierre Sudreau (1919-2012), leader of the Foreign Affairs Committee at the National Assembly. There was also Arthur Conte (1920-2013), historian and writer who would publish in 1981 the book “L’Homme Giscard”.

In Xi’an Giscard was one of the first Western dignitaries to descend into the pit of the thousand terracotta warriors of the tomb of Qinshi Huangdi the First Emperor of Qin (the origin of the name CHINA in the West), then still under archaeological excavation (the first trench open to the public dated from October 1, 1979, a year earlier). What a symbolic presence in the tomb of the First Emperor, a high place of mortality for the powerful of the earth, while forty years later he will be buried in a village of France in all simplicity, in complete privacy in a small cemetery, his coffin soberly draped in the tricolor and the blue of Europe.

In his thank-you speech to the Governor of Shaanxi Province and to the Xi’an authorities, Giscard made a point to thank them for their hospitality towards the large group of French journalists. Francis Latreille told me there were more TV channel cameramen than photographers, who numbered no more than four or five. Therefore, they had to work in “pools”, to avoid crowding too many people in the same room, a photographer would be designated to represent the dailies, another for the press agencies, and they all shared the photos thus taken.

In Xi’an, images of terracotta warriors had until then been only an exclusive privilege of the Chinese news agency, so French photographers really appreciated the opportunity offered by Giscard. Francis Latreille admits later that on his return he “sold well” internationally. I asked him his personal impressions of VGE, his answer: “He was most probably a misunderstood character, a man rather of great generosity, often mis-interpreted by the intelligentsia and the journalists. He was a much more accessible person for the photographers who crossed his path. Giscard really wanted to be in contact with the French people and to listen to them. Francis had previously covered his election campaign, he remembered that one day VGE asked him what he thought of the elections, as Francis was fumbling with his reply, he then asked him to call his mother, this is how Giscard took knowledge of the opinion of Francis’ mom on “pension reversion”, which he would include in his reflections to address France’s pension reform.

Valérie Giscard d’Estaing was also the first Western head of state to address young Chinese students at Fudan University in Shanghai, where he also set up the first French Consulate General, which this year indeed just celebrated the 40th anniversary of its creation.

For the record, Francis Latreille said that VGE loved to come near the photographers instead of going to the journalists who were waiting, to ask them the same question “how did you come? ” By plane, by train, but he did not really bother with the answers, and jokingly Francis once replied: “by pedal boat”. Apparently, from what Francis had heard, Giscard’s successor President Mitterrand, would ask the same question, but in a roundabout way, it was “how are you going to leave? “.

Jean Loh