Manfred Heiting, the most important photobooks collecter in the world

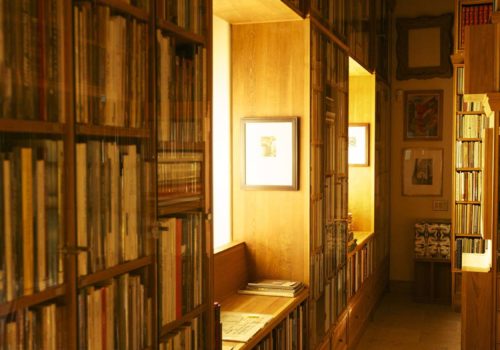

Arles puts photography books in pride of place. This is why we’re publishing today a portrait of Manfred Heiting by Jeff Dunas. Manfred is the world’s foremost photography book collector, with several thousand volumes carefully ordered in a sublime Malibu property designed especially to house his collection. For the first time ever, Manfred has agreed to be interviewed. Here it is in black and white!

Manfred Heiting can be accused of a lot of things – he’s brilliant, autocratic at times, has his opinions to be sure. That being said – he’s taken the time to learn and understand the subjects upon which he is arguably expert. He is currently obsessed with learning as much as humanly possible about the arcane genre of photo-books, documenting them all in infinite detail, and preserving this mass of ephemera in data bases that will be available as reference for future scholars. He combs the world for the prize books he needs or desires and once at his home / lab, his assistant photographs each book in thorough detail and he then notes all the known data for the book; publisher, copies printed, dates of publication, subsequent editions, versions and permutations, size, printing methods, paper choices, binding, packaging, jackets; essentially every possible criteria and inputs this data into a monolithic collection of information that Manfred delights in referencing – he does it all himself, “not to able to blame others for mistakes.” If not for Manfred Heiting, future scholarly research on the subject of many rare photography books from the 1890s (when the autotypie process for printing became available) to late 20st century could and probably would be lost forever. All this will become available on a website – free for everyone interested. He jokes – now, when a collector believes he is being “sold a bill of goods” by a rare book dealer, he’ll have the complete story at his fingertips to make an intelligent buying decision with knowledge and confidence.

One of the most interesting collectors I’ve met, Manfred helped me to realize early on what a true collector really was. Beginning in the late sixties and continuing through the early 21st century, he methodically combed Europe and the US to meet with dealers, curators, other collectors and auction houses to locate the best examples of the best photographs he felt contributed to his print collection beginning with the earliest work available from the 19th as defined by his quantum knowledge of photographic print-making.

He’s outspoken on many subjects but his arguments ring true and reasoned. He makes salient points that young and mid-career photographers would do well to understand and implement. He is virulently critical of the limited archival characteristics of most digital printing until recently and one can understand that he made the decision to completely ignore most digital prints at the end of his collecting period. The same goes for traditional chromogenic prints. He studied the processes – he knew before many of his fellow collectors and most museum curators that color prints made in the 70s-80s were not going to last (citing his admiration for the teachings of Henry Wilhelm – an expert on this subject). Prints in museums and private collections are in jeopardy of or have already significantly faded or deteriorated. He understood the processes and the limitations of color printing and decided it was best left to commercial (ephemeral) applications. He also advises all photographers who are working with digital printing today to carefully notate, on the verso of all prints, the date the print was made, the machine it was made on, the number of ink-jet colors that was used and the exact kind of paper involved in the printmaking. Why? Because already intimately acquainted with the vagaries of the restoration process of silver prints – he understands that this may not be possible with machine-made photographs in future. Digital prints, having come into being far earlier than they theoretically should have without the science to insure longevity, and having undergone so many generations of materials in such a short time, have been fading at an alarming rate and many early prints are now gone or nearly so. How will restoration be possible in the future for these works? Possibly it will not, but without these critical notations, no possibility will exist.

He began his career as an art director – a young art director at that – working for the international divisions of the Polaroid Corporation, the fortuitous result of a tip by a friend who happened to see an advertisement in the International Herald Tribune. He was hired over more seasoned candidates and for many years was a key figure in the international marketing programs, product introductions, trade shows and most importantly, in the building of their famous Polaroid collections, of which there were two – the collection he set up in Amsterdam and built for the corporation in Europe and the American collection built under the stewardship of Eelco Wolf and others in Cambridge – at the company’s headquarters. His job included the launch of the vaunted SX-70 in Europe, the use of the 8 x 10 inch film and the amazing 20×24 inch camera and for the early exhibitions of photography at the Photokina trade show in Cologne. During the mid-70s, employing his ever expanding knowledge of the craft of photographic print making, he began to personally collect examples of great pictures from the 19th and 20th centuries. After leaving Polaroid, he worked as the PR Director and Executive Publisher for the European division of American Express in the 80s. During that time, he also founded the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt gallery.

He may not have imagined that one day his collection would rival the best in the world, in both private as well as public and institutional hands, but ultimately that is what it became. World Class. Knowing Manfred in those days, it would have been quite apparent, however. His collection was curated not by happenstance – oh no!, but based on the quality of the prints themselves and the position they had in the life-work of the photographer. He wouldn’t rest until he possessed the finest example of an image he searched for and his critical eye was known to be among the best. He would research a photographer completely, understand where and when an image was made, what the circumstances were at the time the image was made, when the photographer made prints of that image, which were reputed to be the finest the photographer ever made and find that example. Own that object. With those criteria – his collection became singular – other collectors had those images, but if he could help it – his had the better, if not the best prints.

So for Manfred, collecting was elevated to a very high level – as distinguished from accumulating or “investing” as many erstwhile collectors are actually doing today. He loves to learn and once he transferred his collection to the Museum of Fine Arts Houston for a financial arrangement that has yet to be publicly announced, he was able to turn his exacting collecting criteria and new financial wherewithal to the genre of photo-books – and just in time! Photo-books had not really come to the attention of modern bibliophiles until the publication of Andrew Roth’s game-changing book, The Book of 101 Books: Seminal Photographic Books of the Twentieth Century, in 2001 (most of the specific examples presented in that book – are now his). Yes, Fotografía Pública: Photography in Print 1919-1939, was published in 1999, but didn’t have the urgent result of sending hordes of collectors suddenly lurching about trying to get a copy of each book in the compendium that Roth’s book did with the result being people were suddenly paying instantly inflated prices for titles that could have been had prior to its publication for 25% – 40% of the new “values.” Of course, the accessibility of the internet helped to artificially inflate the prices as well.

As he did with his print collection, Heiting applied his practiced determination of possessing the finest examples obtainable of each book in his collection, now numbering over 25,000 singular photo-book titles and he now, once again, owns a singular collection to rival all others.

A visit to his library is akin to the holy grail for photo-book collectors. Yes, there are a few other collections that even he admits are spectacular and the list should include Martin Parr’s and for “real” artist books, Phil Aarons’ – but his is again, in true Manfred Heiting style, perhaps the best. The difference? Not quantity, but quality and completeness. Manfred knows if a book came with a belly band or a shipping case, and if it did, he has it. By comparison, other massive collections contain basically reference copies. Being German, and having been raised with a very European sensibility, the library is a solemn citadel of respect for the remarkable contents within – as he says: “In memory of what was lost in my country.” The library is “headed” by an entrance shield with a quote from Borges: “I have always imagined paradise to be a kind of library” – and he certainly believes it! Ask to see a copy of a mythical book and he may produce two or three gorgeous copies – each with their own peculiar attributes and the story you’ll never hear elsewhere about its history. He knows his books. He spends 12 hours or more each day in the process of collecting books or searching for them and talking to his network of experts who help him with information – a pursuit that pleases him most because it affords him the luxury of intense scholarship and methodical searching while building his immense collection of photographic books. There is no way to encompass Manfred Heiting in a short, punchy interview – each session is nearly inexhaustible and opens door after door which the engaged journalist must carefully select. I’ve tried to open the principal doors – his early years, his years at Polaroid, the genesis of his renowned collection of photographs, his new obsession of assembling his second world class collection (photo-books) and though not a door like the others, his valuable philosophy and ideas on a broad range of related subjects.

JD: Herr Heiting – You’re the quintessential collector.

MH: If you say so – but indeed, even before I collected photographs I collected. I started collecting colorful paper when I was five years old. In 1948 everything was gray in Germany. There was no real color in our life. Clothing was gray – color required special dyes and were not available – so everything was gray. Shortly after the war we lived close to a dump that a local printer used for paper-left-overs and misprints. When you saw yellow or red or blue of anything – it was something! I stacked those colorful papers – they were the size of calling cards – a wonderful collection . . . obviously, I don’t have them anymore. After the usual stamp collecting and buying some books with covers designed by the Celestino Piatti [the famous Swiss designer] – which I collected at the age of 16 – I met the leading group of Dutch ceramic artists at an opening of their show at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. That was my first encounter with art & craft. Shortly after that came etchings, art deco and art nouveau posters, photography and photo books.

JD: Collecting can be thought of as a kind of mania too….

MH: There’s a funny little story about an English collector known in the 19th century; no one really knew what he collected – it seemed everything. He had a big house but no one ever visited him there. When he died, people were there dispersing things. Everyone in the town was curious about what was in this house! The house was completely filled with boxes; all had labels describing its content. Then they came to the basement – and in a corner there were more boxes with labels that read: “Not worth collecting”! [Laughter] Heiting: “But I am not that bad . . . !”

JD: Define collecting, Manfred.

MH: So a collector is basically a keeper of things – but then you have to make your choices: Paintings, photographs, books, diamonds, gold coins, stamps, ceramics, posters and furniture – or whatever. The important thing that makes a collector is not the quantity of things he has, but whether he understands what it is he /she is collecting. If you don’t know what you have or what the particularities are, you will get lost. And – you should buy with your eyes and your brains – even with your gut – but not with your ears. Most people today buy with their ears. “Have you heard …”.

In photography, you can find a Weston print for $50,000 and then you find the same image for $10,000. People might think the guy who paid $50,000 was a fool, but perhaps not! He probably had the print and not a secondary or lesser copy. You have to have that knowledge if you spent your mortgage on a print and whatever else you acquire! You can’t have money telling you what to collect. It is knowledge, experience – and passion. When you start, you will make mistakes but you also learn by doing. In 10 years you will know more than in the beginning. In 20 years you know even more – but you never finish learning. There is no “How-To” in collecting. And at the end it is about knowledge! Today, you can always get information on the internet – but people often don’t want to hear or try to understand.

JD: For example?

MH: Take analog color prints in the 1980s; no private collector had a cold storage at the time – most museums did not have one. But a stable, controlled “cold” environment to store color prints was required! Henry Wilhelm was preaching this to all who listened – as far back as 1973! Of course you could buy color prints and decorate your apartment or store them in a print box and look at them at X-mas – to discover after 20 years they had deteriorated, shifted color or faded! If you paid $800 – great, you have enjoyed a wonderful image for 20 years. But if you paid a half-million – not so great! Today, cold storage is a “must have” for all collectors and museums to house their contemporary color works – but still, very few have one (including museums). And many have only small “refrigerator” units for smaller prints – but that does not work for a 10’ Gursky . . .! There are exceptions [color prints not requiring stringent cold storage] like carbon prints, Fresson prints and of course dye-transfer prints, but since Kodak no longer produces that material anymore, it is no longer a viable option and hasn’t been in quite some time. Of course, not everyone likes Fresson prints and color carbon prints are an art of their own – and very difficult to make. This basically means you cannot collect analog color photographs – if you do: you better take action – and very few collectors or curators want to hear this. Digital prints are a completely different animal and the first 10 years of their use is a real mess. Since the introduction of pigment-base inks you have a reasonable chance that your grandchildren will still enjoy the prints – but a word to the wise; a temperature-controlled environment is still required! One more caution: No face-mounting! No way to restore face-mounted prints – air comes in between the layers – no matter what!

JD: You once said some people are accumulators and some are collectors.

MD: Yes, that is true in every field. You can have a Miro, Stella or Ruscha on your wall and call yourself a collector or think you understand paintings. It could just mean that you have money to spend and somebody told you these where great names to own – and you have “accumulated” works by good artists (you also may have made a smart investment). If you know all about Rauschenberg, de Koning or Rothko, and if you understand something about paintings and their work, then you may not necessarily want to own a particular example – . They are all recognized as great painters but no artist made every painting a great one – sometimes not even a good one. If you are a real collector, you must have passion for what you collect, have an understanding of art history, be knowledgeable (as I said before) about the specific field and how your treasured artist fits into the larger history – have read their biographies, followed the developments in the art market – and than you would be in a position to make an informed decision about acquiring work for your collection; you’d be able to make an informed choice.

JD: You also have a philosophy about collecting photographs.

MH: Yes, sort of. The camera always takes an image of what is in front of the lens (which of course the photographer directs) and then he or she would bring that image to life in the darkroom. Before digital, the darkroom was where the print was “created”: by the photographer, not in the camera. In photography – the negative is absolutely not the “original,” It is the print! The print is the “object.” The collector collects the print!

JD: The print is where the emotional response resides.

MH: It’s like with music; the negative is the score of the photographer. But it is the performance you fall in love with! You don’t want to listen to someone play all the notes as written, you want to listen to Pablo Casal’s interpretation of Beethoven’s 4th

Symphony. August Sander’s prints are not exactly brilliant, but they have the emotion and interpretation he became so famous for! Now, you can have a service bureau make technically perfect prints from Sander’s negatives – but so what? – it’s not the object you’re looking for. From one of Ansel’s negatives, no master printer can make the same print as he did. It is the master print made by the master himself – in his darkroom – that is Numero Uno. Look at 10 different prints of his Moonrise [Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941]: In the early prints you see mostly clouds! They’re mushy! Later he intensified his negative and in the 1950s and 1960s he made the most beautiful prints! As he grew older, there were less and less clouds – and ultimately the sky was printed nearly completely black. His vision grew “older”. Many people wouldn’t know the difference. But that’s what collecting is all about. And of course I have a similar philosophy for book collecting.

JD: I know you have something important to say with respect to the idea of photographers limiting their work.

MH: Why limit? I’m against limiting an unlimited medium. Ansel Adams printed more than 1,000 copies of “Moonrise”. It didn’t influence the appreciation or the value of the image or each print in the least! He is probably one of the most productive / prodigious photographers of his time. I would also say that he made maybe 10,000 pictures in his lifetime. That’s what many photographers today take in a year! I would speculate that Araki has already taken around 1,000,000 – and he is still going strong! But maybe, those should be limited . . .

JD: That’s one wedding today!

MH: [Laughter]. Yes, and how are all these books getting to the bookstores? There are probably about 3,000 or 4,000 photo titles published each year (Steidl alone makes at least 120 new photo books each year). Yes, please, more limiting . . .

JD: We should back up a bit. You started as an art director. Did that experience help develop your acuity as a collector?

MH: Yes, of course – it has trained my eye for form, beauty, esthetics and quality, but equally important was my early training as a typesetter at one of the most prestigious printers in Germany at the end of the 1950s: I was trained in the applied craft of typography, layout, printing, lithography, retouching, darkroom work, etc. I knew next to nothing about photography when I started to “buy” my first photographs at the end of the 60s, yet, I was lucky, working with wonderful and enormously creative and visionary people – and mentors – at Polaroid Corporation in Cambridge: Bill Field – responsible for design; Ted Voss – responsible for advertising; Eelco Wolf – responsible for PR, Dr. Richard Young – President of the International Division and of course Ansel Adams – our in-house photographer. These – and many other colleagues shaped my understanding and love for the field.

JD: I’m sure the experience of working with Ansel was instrumental in how you approached collecting photographic prints.

MH: Yes – very much so. Working with and learning from Ansel was the foundation and inspiration for my pursuit. Ansel was a master of the print. He was so technically versatile (particular in the dark room) – he could not only exercise the right approach, he could explain them as well. So if you could listen, read his books, understand and apply what he set down, you were ahead of the game. I had the best training at Polaroid – and not only from Ansel. During my employment at Polaroid for over 18 years (and consultant until 2000) I met – and worked with most of the great photographers of the latter part of the 20th century.

JD: So you could say that being in the position you were in at Polaroid had a seminal influence on your later development as a collector.

MH: Well – being responsible for the design of promotional, educational and packaging material for one of the great photographic companies of its time, I was blessed by being at the right place and time – and working with the right people. It also just seemed that I had the right perspective and methodology to source the best work and example of craft of the photographer’s work I “discovered” – and of the images I liked.

JD: You started out at Polaroid as an art director and later were instrumental in building their spectacular collection of photographs.

MH: I was always the international art director at Polaroid – whatever fancy titles I was given later. And yes, I did set up the International Polaroid Collection.

JD: OK – so how does a young German art director get the job you had at Polaroid, particularly in Holland at that time?

MH: With lots of luck! After my 3-years training at the printing house and my military service (during which I had some evening classes at a famous design school in Ulm), I worked for a few years for several advertising agencies. I moved to Holland, and eventually got the job at Polaroid. Back then, remember, Polaroid was more about sunglasses. For many reasons, its international headquarter happened to be in Amsterdam. I went through the application process and had several interviews. In the 1960s – the last thing you wanted to be in Holland, was German! For good reason! Finally the head of the international division said to the Amsterdam team: “OK – there are two final candidates. You choose. But I warn you – don’t take the German!” Well, they choose the German…!

JD: Did you ever work with [Edwin] Land directly?

MH: Yes, a few times. Polaroid was one of the most brilliant and entrepreneurial companies – and he was its soul – and engine – and one of the last true geniuses of his time. The SX-70 was Dr. Land’s ultimate – and immensely successful product; the most ingenious camera and film system ever made. In 1979 I was asked to develop and design an exhibition and catalogue on the history on the dye-diffusion process for a museum in Belgium. This was a very sensitive historical project to present to the public since it included early patents by an Agfa Geveart scientist, as well as from Polaroid (which ultimately became instant photography) and had to be handled as diplomatically as possible. To develop an exhibition of that nature you needed to involve the scientist – which meant Dr. Land himself – on a regular basis and over a period of several months. What I learned working in Dr. Lands sphere of interest was his ability to articulate a response to a part of your work that illuminated and directed one’s own thought process, resulting in your own improved ability – opening the way to an easier and much more successful path than you would have ever imagined. It was an on-the-job training I never experienced in my professional carrier again.

JD: There’s a connection between Land and Steve Jobs.

MH: Dr. Land was Steve Jobs’ hero and role model. The difference between those two incredible men was that Land was basically a scientist and thought only about how science could improve the world we live in. That being said, he was basically a “lab man” – surrounded by trusted co-scientists and interested in all aspects of his inventions (he had over 500 patents). Steve Jobs was more brilliant in understanding what products and their applications customers would desire, even before he or she thought about it, and was ultimately more successful in building Apple than Dr. Land was at Polaroid. Also, the era was not on Dr. Land’s side. Although he was very keen to know what the marketing people where up to – and we, the creative types, benefitted from this in no small way – he was not in general, a micro-manager as Steve Jobs was.

JD: Ok. How was the Polaroid Collection created – did you buy directly from photographers and artists?

MH: Yes, but for decades there was always a policy of “keeping” perfect and interesting pictures made on Polaroid films for research and reference purposes at the company. With the introduction of the positive/negative films, the SX-70 system and then the 8 x 10 and 20 x 24 inch film, our efforts in locating and retaining these images became more focused and more useful in many ways – and thus, more administrative, logistical and financial procedures where established.

JD: So you were then given budgets to actually compensate photographers with.

MH: Well, it gave me and my Cambridge-based colleague, Eelco Wolf, the ability to establish budgets and to contact and work with professional photographers, artists, scientists and amateurs alike, acquiring by barter (material and small, token amounts of money) a vast spectrum of photographs. This provided an enormous resource of images for our PR departments, cultural activities with museums, magazine portfolios, publications, trade shows and of course, ultimately the Polaroid collection. This also broadened and influenced my view of photography– and my future collecting sensibility. Long lasting relationships with Warhol, Mapplethorpe, Kertesz, Hockney, [Lucas] Samaras, [Marie] Cosindas, Newton – even meeting Josef Sudek on a job – and many, many others are my biggest personal “treasures”.

JD: Warhol was heavily associated with Polaroid cameras.

MH: Warhol loved Polaroid’s fixed-focused camera called the Big Shot. He used this camera for cover pictures of Interview. It was a “big” cheap plastic camera and he lost it very often – thus, Vincent Freemont (his studio manager) gave me a call: “. . “Andy needs another one . . . “. So that’s what the collection gave me – access to a lot of creative people I wouldn’t have ordinarily met. And we acquired a great many variety of images – I didn’t need to love or even like every one of them.

JD: So you begin to collect for yourself at the same time as well as for the Polaroid collection?

MH: In a way it was to be expected: In Arles [Rencontres International de la Photo, later the Rencontres d’Arles photo festival] I met all these young photographers – many I had never heard – and began buying contemporary photographs for myself (it was very inexpensive in those days). I remember the first ones I bought were from Luigi Ghirri. I was blown away – and it was all in color! I couldn’t buy his work for Polaroid because he didn’t’ yet work with Polaroid materials (of course he later did – using the 20 x 24 camera). And also Shoji Ueda – a great Japanese master photographer – his black & white images are historic and his color work with people in motion, . . . stunning. In 1985 I gave them both shows at the Fotografie Forum Frankfurter – the institution I set up and ran for 10 years in Frankfurt. I also still have many Polaroid prints in my personal collection – gifts that I never considered “precious” . . .

JD: The way we think nothing of emailing pictures today – …

MH: Right. In the beginning I collected 20th century work for myself. That was where my main interest, heart and passion was. Because I was early, I had more opportunities to find “the right stuff” – than anyone would have today (regardless of how much money is involved) – and then, the time the work was available! I was one of the few people who really grew up in photography – from my early 20s until today – 50 years! Photography was very good to me.

JD: One could say you were one of the collectors who understood in the ‘70s that the time was right. The second wave.

MH: Not really – I did not understand much at the time – for me it was not about timing or planning. I came to collecting photographs at the end of the sixties because of my work at Polaroid, thru the many people I met while there and with occasional visits to MoMA and the few other museums in Europe and the US. My first visit to MoMa was in 1966 on the occasion of the first one-woman show of work by my long-time friend, the eminent Polaroid photographer Marie Cosindas. Of course, there were several people before that period who had acquired large archives of photographs – but they didn’t really collect – as we understand it today. At that time there was a “surge” in the interest in photography because of the media: Magazines, TV, films – and more and more books. Museum started to look into the idea of taking photography more seriously. Of course, I have to say that Polaroid also helped, and to a much lesser degree Kodak, Agfa, Canon, Leica –all helping to shape the time to be right. Not to forget, the prices were very low – even I could afford it – today: impossible.

JD: Talk about the influence of Venizia ’79.

MH: It absolutely served to accelerate the positive perception of photography by a wider professional audience and – you may call it a closure of the “second wave.” The ICP – under the legendary Cornell Capa, organized Venizia ’79, – it was four years in the making. The most influential and respected people from the whole world of photography at that time attended. Over 40 exhibitions, plus workshops and lectures. I was there with my team and the just introduced Polaroid 20 x 24inch camera system. We had an historic show there – It was fantastic and very rewarding for us. I also had the chance to meet everyone there. Harry Lunn came with Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson had a great show and came with [the great French photo-book publisher] Robert Delpire, Peter Galassi . . . As a singular event nothing has ever happened like that again.

JD: When we first met in the 80s, you were at American Express and running the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt.

MH: Yes, we met in Arles – mid-eighties – when you were running your magazine. [Collectors Photography]. I left Polaroid in 1982 (I was not ready to move to Cambridge whenPolaroid decided to close the division in Amsterdam). I was still contracted to design and manage Polaroid’s participation at Photokina (and did until 2000) – so I moved to Frankfurt and tried to open a non-for-profit photography place there. This was the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt. It was quite an experience! I was very naïve to believe it would just “happen.” It cost me a lot of personal time and money; I had no outside support. Frankfurt at the time was not Amsterdam . . . so, in 1983 I realized I needed a job to survive. I came across an ad in the Frankfurter Allgemeine: American Express International was looking for candidates to fill the new position of communications and PR director. At the Venice show I had met one of their directors from New York who ran their cultural department and they were acquiring Cartier-Bresson’s show from Venice – so it seemed an interesting company. Anyway, it was a bit of a long shot: they had hired a major head-hunter firm to select the candidates – a lengthy process. Apparently my references helped – I got the job – and the Fotografie Forum Frankfurt was saved! In retrospect, the FFF represented a wonderful opportunity to meet new faces in the field – particular in Germany, which I had left a long time before. I organized over 60 exhibitions during my “tenure” there. In 1989 I moved to Brussels to set up an independent Amex company to develop their magazines for Europe so I found Celina Lunsford to run the gallery and she is still involved today (finally the city of Frankfurt did subsidize the gallery).

JD: So while you’re living first in Amsterdam, then in Frankfurt, then in Brussels, you build up your collection – Wasn’t it originally primarily 19th Century?

MH: Yes, but I was not only looking for 19th Century –I was fascinated by working on a more encyclopedic collection (at that time I was already quite advanced in European avant-garde and Bauhaus-related material) and the British, French and American 19th Century was an important task along this road. Trained by Ansel, I was looking for the best prints that I could find – not at all easy for 19th Century material. It would have been a failure and I could not have achieved my goal without Harry Lunn. He guided me. He also guided many more important “clients”: the Met, the Canadian Center of Architecture, the Gillman company, Sam Wagstaff … and other collectors, thus, I was always third or fourth on the waiting list for perfect material! If one of them didn’t buy it – I got a chance! He helped me a lot – not only with acquiring the best prints (even if these did not come from him!), but also with the so much needed information – and as my “banker”! He let me pay over time – sometimes requiring years. You don’t have that anymore today.

JD: There must have been competition for the prints you were after?

MH: Well – in the 1970s to 1980s there was always a small group of collectors who nipped at each other’s heels (and certain dealers always tried to keep it that way) – many with greater resources than I had. Those included Sam Wagstaff (he sold his collection of primarily 19th Century and early 20th Century to the Getty); Thomas Walther, who had one of the best “eyes” in the field); Werner Bockelberg, a very successful commercial photographer from Hamburg with an amazing collection of early Daguerreotypes, now at the CCA and other places. Bockelberg also had a few hundreds pictures of the early 20th Century in his collection that were like a string of magnificent pearls. He sold that collection to Sheik Al-Thani; Pierre Apraxime, collected for Howard Gillman – one of the best collection ever assembled by one person – certainly not on an economy ticket (now at the Met); Richard Pare, who built a priceless collection of architectural photography CCA; Wilfried Wiegand, a known German art historian and author of the early history of the medium and Roger Thérond, the editor of Paris Match – a so called French collection – with the appropriate highlights of 19th and 20th Century photography. Last but not least: Michael Wilson, probably the most knowledgeable collector of 19th Century photography and today possesses certainly the most comprehensive collection – including modern and contemporary, still in private hands. Back then, however, as far as I can recall, I was one of the few who intensively collected contemporary photography in addition to 19th century (because of my experience and contacts at Polaroid).

JD: So by the time you sold your collection, you knew it was world class.

MH: I had an idea – sure. During the 1990s I became more known as a collector, and was on the “Loan-List” of many museums around the world – but no one knew much about me (Art News, Art & Auction and Art in America had all sorts of stories and rankings). However, I had always lived either in Amsterdam, Brussels or Frankfurt – and the photography market was and still is here in America. In the late nineties, American Photo wanted to do a story on collecting and interviews with the ones they knew. When [Editor at Large] Jean-Jacques Naudet asked me to participate I was very honored to be included. I also I gave him an interesting idea: get them all to New York and make a picture of all of us together – which he did! It was actually a very nice picture taken in the antiquity section at the Met (I wish I had a print of that image!) This event moved me closer to that class . .

JD: If I were to guess, I’d say you probably didn’t think much about selling your collection as you were building it.

MH: Well, yes and no. I never thought about it as my 401K (not possible in Europe anyway), but by the mid 1990s, I realized that I did not have the means to continue the contemporary part of the collection the way I thought it necessary (having a “dog” from every “village” was not a convincing way to build an encyclopedic collection). I also became aware that I could not take my collection with me! In 1995 I started to produce what eventually became a 4-volume publishing adventure with about 1.000 images (about 20% of the works in the collection) to present my take on the image history of the medium – and to share it with others. The sumptuously printed four books (divided by country or subject matters and in chronological order) represent the collection quite well. I also included texts from great writers on the subject to get it all in perspective, led by Eugenia Parry and including Anna Fárová, Wilfried Wiegand, Jim Enyeart, Ann Tucker and others. I had to self-publish them and could only give them away! No publisher could or would have paid for all the rights – nor agreed upon the quality that I insisted upon which was vital if the reproductions were to ignite the passion of the viewer as seeing the original prints had done for me. Seeing these volumes eventually had the effect that the Museum of Fine Arts Houston wished to own the originals.

JD: Did you have any misgivings after selling the collection?

MH: No – no. It was also not just a sale. I gifted a large portion of the collection and in ways it will still bear my name for many years after I am gone. As such, the gifted part of the collection will always be remembered that way. The museum also has my professional archive – and there will be more in the future. I am very pleased and honored that the museum will house all of my life’s work.

JD: This interview wouldn’t be complete without you briefly telling us the story of the fake Man Ray you acquired.

MH: Two years ago I had to face the fact that in 1990 I had acquired a very important (and expensive) vintage, estate-stamped, Man Ray print from a reputable dealer in Paris (at least at the time) that turned out to have been a later-printed “fake”: The stamp was a manipulated forgery. The provenance was said to be Lucien Treillard, Man Ray’s secretary, who conveniently died a few years later. Due to the time elapsed, legal recourse is not an option in France. There is also the case of the Lewis Hine forgeries in which a most respected photography archivist – Walter Rosenblum (husband of Naomi Rosenblum) printed Hines’ most famous images and sold them thru several New York dealers and represented them as vintage prints by Hine. I had three great “Hines” images bought from one of those dealers. The case was settled out-of-court and the dealers returned the money after a few years. So, I had my fair share in contemporary greed.

JD: How do you define “fake”?

MH: A “fake” to me is when a signature, stamp, attribution or assigned provenance is false, manipulated or willfully changed. A later printing date is not a fake – that is simply trying to fool buyers to make more money (if the prints were made by the same acknowledged “printing source” as the vintage prints). The French legal system had an interesting take on this position which goes more or less like this: If it’s printed from the original negative, it’s always an original print! In the most famous case in point (again with Man Ray), a noted German collector bought around 100 “fake” – but quite stunning vintage prints – for an alleged $2 million. It was clear they were made from the original negative, since most of them had “more image” on the print than we all knew from reproductions. That the prints were made later (and of course not by Man Ray’s acknowledged printer) was a market peculiarity – according to the French judge – and did not have relevance in the case! As we know, several printers made prints for Man Ray after the war, so several of them had his negatives, and could easily have made more than he authorized, or made them “later”. In 1995 his negatives went to the Centre Pompidou, but some were never found as he had died many years before. Man Ray prints will always be a tricky situation.

JD: Now we get to the third phase of your collecting …

MH: Well, everything I collected is related to the craft of the field – ceramics, etchings, posters, photographs – and now photo-books: yes. I must emphasize, I’m not an Art Collector.

JD: So you – suddenly turn to books!

MH: Not so sudden. I bought photo books as far back as the 1960s – what ever was available at the time – for reference and to learn more about the photographers I met or whose work I’d seen. Around 1994 I started to look more and more beyond what was published before and during my professional life. Particularly at German and Russian books published between the wars and at Japanese monographs until the 1970s, when there was still uniqueness to their photo books. And after I transferred my print collection to the MFAH, I focused even more seriously on collecting and researching photo-books from 1895 (around the time the autotypy process became available) until the 1970s (when a book had still the character of a book and was not just printed color photographs on paper). When I buy a book, I’m not only looking at the pictures, – I’m looking at everything else; text, design, typography, print quality, paper, binding, etc. And that’s why I pass on most books published during the last 15-20 years; most of them look the same. Now they’re all well produced and contain primarily color images (black and white is much more difficult to print)! With less and less text – or no text (it is very challenging to say something intelligent about boring pictures).

JD: Would you admit to being somewhat obsessive? Slightly? [Laughter]

MH: Yes!

JD: Manfred, You have custom slipcases made for your books!

MH: Yes [laughter], but not all! – I do protect each book with Mylar. The oversized and large soft cover titles are protected in slipcases made in-house or at a place in Poland (for magazine runs or same size cases in quantities) and for the better and more fragile books, clamshell boxes are made by a Dutch craftsman in Brooklyn.

JD: It’s still about having the best examples – and it requires knowledge!

MH: Absolutely. First I like to say that I have learned much more through books about photographers than I ever could have known from collecting their work available in print – only a fraction of any good photographer’s work is available as original prints. Unfortunately today, there are more uninteresting images available in book form than ever before. Many, still young photographers, have 10+ books out already. In comparison: Stieglitz had only one book in his lifetime, Weston three and Strand a few more by the end of his life. You can imagine how much care in selecting those images for those rare occasions was taken by those master photographers – versus the “annual” book selection of these contemporary “art photographers” and their publishers. I really respected more photographers and their books prior to the art boom (1970) than I ever did subsequently. It’s much more interesting to study in archives, libraries, museums and antiquarian bookstores than looking at publishers catalogues or the general bookstores of today. I probably spent 20-30 full days a year in those places to look, to find, to make notes, ask for images, etc. and make new friends – I love it.

JD: How many volumes do you have in the collection?

MH: Now I am approaching 25,000 photographic titles – not including duplicates, books on art and design and those published in the last 15 years that I own but which I don’t’ even have in my database yet. The number also includes catalogues – which I consider very important – in particular the ones before 1980. Book ephemera are a very useful source for information and I always try to find items – particular from before the war.

JD: We once talked about the value of a signed book in your estimation.

MH: I don’t object to signed or inscribed books, but dedications, with few exceptions, don’t trump quality. You can’t always get books in perfect conditions – but it should have all the elements (complete as published), and be a perfect image of what was there. I’m collecting the object! I want the copy in my collection to be as close to the original state as possible for future scholars to study. With photography books my rule is: If you don’t have the jacket, the bellyband, the original binding (I am easy on not having the original protective slipcase) – you have an incomplete book (in the 20s and 30s, often the picture on the jacket wasn’t reproduced in the book). If you have a copy with no jacket but it’s signed – you still have an incomplete copy! Before 1960 books with the dust jacket are rare because many buyers of books and most institutions threw away the jackets – or they rebound the books (The New York Public Library made this ultimate sin!). My photo book collection is driven by my database – which includes images of every related part of a book. There I collect the information first – and many times it guides me to find the actual – and complete – book. Because of that, I have many more books in my database then I actually have in the collection.

JD: Is this the last collection? Will the 85 year-old Manfred start again?

MH: No – but you know – this is fun. I’m learning so much by doing – so much! For me, 20th Century photo books is not only the history of photography, it is also about our own history, history of many countries and the wars in which we have been engaged, history of publishing, of printing, of people – it all come together in photo books. The journey through all this is the destination.

JD: I think you’re an artist, Manfred because you bring a great deal of artistry to what you do in your commitment, opinion and output.

MH: . . . but who isn’t? [Laughter] – We use this word very lightly. It’s about creativity, esthetics and craftsmanship. These are all attributes relating to craft. I believe photography, etchings, ceramics, books, posters, furniture, fashion design – are all part of the decorative arts (arts & craft). But, I have no objection of calling a bookbinder a book-artist – he does things with his hands like a sculpture. Today the fashion photographer – he’s an artist . . . the commercial photographer – he’s an artist too, so is the amateur (Avedon called himself a photographer, Helmut Newton hated “art” – he was a self-professed “gun for hire”)! It seems to me, it is all made for the “art market” (art has more value); you have a nice book, you make a slip-case for it and put an original print in it and – Presto! You have an artist book! [More laughter]. It doesn’t mean that in some instances, once in a while, these “labels” can merge – but to use it as default? Anyway, I am totally against calling every photographer an artist and artificially limiting photographic prints. It is so terribly damaging for a young practitioner.

JD: This is important – hopefully your skill-set increases and you are capable of making a better print at 40 than you were at 30 – and to that point – possibly a better print at 55 than at 40! Limiting prints at the beginning means you’ll never bring any more intelligence or skill to bear on that image. Perhaps it’s seen as pretentious. Or an outright lack of insight as to where you’ll be in the years to come.

MH: You are absolutely right! It all started in the 1970s with the idea of “Portfolios”; – inspired by the idea of a possible way to sell photographs, a photographer made a selection of 10-12 prints of his work in a limited portfolio sets of 20-50 copies – for “only” $1,000 to $2,000 per portfolio – depending on his or her status. Of course they had one or two “famous” image in there – and added others (after all they where still young but noticed). What happened then was they could never print that good or famous one later on because they had limited it in the portfolio set! Of course many of those portfolios went to museums because of the tax benefits for the donor and they are buried there, they are dying there! Many of the museums started to collect photography in the 1970s and have many portfolios from that time in their collections. I am sure that no one ever looks, sees or uses the portfolio images in exhibitions. Today we have the photographer’s “artist books” (the one with a print) – exactly the same. Why?

JD: Jean-Loup Sieff only numbered his prints. He thought if he put 8/16, not only would he be limiting the ability of the future buyers to decide, he’d be implying there were 16 while there may have only been 8 or 9 ever printed.

MH: Yes. Photographers should not number nor limit their work – only dating the image and the print, etc. PERIOD!

JD: You are engaged in what will probably become your life’s most important project. You are cataloguing your photo-book collection and that of some others in order to have a monolithic reference work available to all.

MH: Yes, my most important goal is ultimately the photo-book database on the internet – including those books I don’t have myself. But for all the books I will have the information from other collectors or institutions. What I want to do is to make sure that future collectors, who are really interested, are not answered by booksellers to the question: “Does it come with a dust-jacket” – “Oh, I don’t think so”, or even – “Well, I’ve never seen one.” Dealers want to sell what they have! Actually, this is how it started for me. I wanted to know. I needed those answers.

There are maybe around 1000 different books listed in todays most quoted reference books – which everyone wants to have. Many of those books are not necessarily the most important books or even the rarest of books! The compendiums were most likely based on what the editors or authors of those reference books had or knew of. I believe, however, that there are many more interesting and important books out there, which have yet to be researched, “found” and catalogued. I would love to spend more of my days in major institutions, publishers- and printers archive researching their books and work. Very often, I find things that I didn’t know I was looking for!

JD: So you do the research. You go to the source.

MH: It’s a pleasure. Yes, I like to research printers archives like Draeger Frerès in Montrouge, Neubert in Prague, Enschedé in Haarlem, Bruckmann in Munich. Many do not exist anymore – It’s a great negligence and crime of those responsible to protect our cultural heritage! I went to the archives of Scheufelen, who made the first coated paper used in many of the better German photo books between the wars – an incredible resource to study their documents and “left over” print examples (I was too late to see it all – I was beaten to it! And of course we have the libraries; in this country: Yale University, some parts of Harvard University, the Getty Research Institute, the Hoover Institute and the University of Colorado at Boulder. In Europe – Deutsche National Bibliotek in Leipzig, The University of Reading, near London and the Bibliothek Nationale in Paris. For the 19th Century – nothing beats the George Eastman House library in Rochester. Photography is not known through collecting or exhibitions of prints, but through books and albums. Libraries were the initial collectors of photography in the 19th and early 20th Century, not museums. They are the source.

JD: So there’s no end in sight for your research program. You’re a patient man.

MH: I always will keep learning – as long as I can go on the journey. And as long as I’m not demented I will try to obtain the relevant information of noted photo-books and will make all the details available on the website – free of charge!

JD: You are listing every possible detail of each photo-book. It’s an endless task. Long Live Manfred Heiting!

Interview made in the Heiting residence, Malibu, California in January of 2013

© Jeff Dunas 2013. All Rights Reserved.