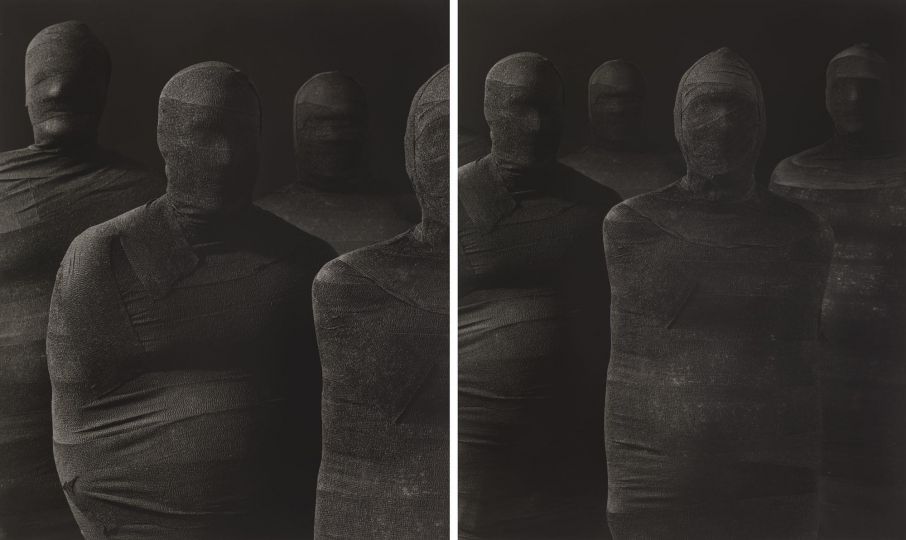

In most of the societies of the coastal region between Ghana and Nigeria, funerals represent one of the most important events in social life. They respond to the need to pay homage to the dead, ready to meet their ancestors, the dead who must be supported, respected and feared, in a constant dialogue. It is like this among the Ewe in particular, who live among other populations in Ghana, Togo and Benin. One part of the funereal rites, by no means insignificant, has been marked, since the 1960s, by the omnipresence of photography. More than simple souvenir photos, these photographic portraits, with their representative but also iconic properties, seem to be the medium thanks to which the dead remain alive and through which the lives of the dead and those of the living stay eternally connected, without interruption, from generation to generation. From all the evidence, the usage of photography has democratised the choice of the funereal portrait. Indeed , if the effigies accompanying the dead or the statues installed on the tombs and funereal chapels were, in the beginning, the privilege of well-to-do families burying dignitaries, notables and chiefs, the more accessible and less prestigious photographic portraits have allowed a much greater number to celebrate and accompany their dead in a dignified manner.Their popularity is such that large amounts of Ewe funereal photographic portraits are spread today not only in the obituary pages of Togolese and Ghanaian television, but also in those of social networks such as Facebook.

The original portrait, made during the life of the deceased and constituting the model for the funereal portrait, is carefully chosen by the family, cleaned, often reprinted from the negative if it still exists, or reproduced by photographic copy, enlarged according to the means and the future needs.If it is not suitable, because it is too badly damaged, old or too fuzzy, more important modifications are involved. Ferdinand Atari Brown (born in 1974), lives in Grand Popo in Benin, but his activities take place primarily with Ewe clients in the nearby city of Lomé, explains the development of the process in talking about his photographs: “The family brings me the photo of the Old One: a single portrait or in a group or even just and identity card photo. I outline the silhouette, I cut out the face with scissors are better on a computer in Lomé. The face is mounted on another body with other clothes; I can change the background; I colourise it when the photo is very old. Everything must be done to embellish the portrait of the deceased that will be displayed majestically in the procession, or that will be seen more simply on small visiting card souvenirs distributed by the family during the funeral.”

Michel Hounkanrin (born in 1954), closely related to the Yoruba, one of the rare photographers in the coastal region who for a dozen years or so, has owned digital cameras and computers in his vast studio in Cotonou, offers the same type of funereal portrait when only the face is that of the deceased, while the body, clothes and background are completely reconstituted with Photoshop.These portraits, originally destined for funerals, have been a great success since the 2000s among a well-to-do clientele, when they are printed poster-size, like a ceremonial portrait, mounted in an illuminated case on castors before being presented and moved into a private apartment. In his own analogue photo lab or in one of the new Korean colour lanes installed for a decade in the coastal countries, Caderi Koda says Labara transforms the original portrait to create the official framed portrait which will have pride of place on the family’s domestic altar, but also for the announcement and the picture destined for the very popular daily obituary columns in the press and on television.

An intense moment in the funeral is the presentation of one or several enlarged and framed funereal portraits to the relatives, friends, extended family, musicians and the wider public during the procession through the neighbourhood of the city or in the village. It is then exhibited in a communal courtyard under a thatched roof on a dais comprising loincloths. During the display of the body at the wake, another photograph of the dead person is set up; the body of the deceased surrounded by the close family provides a portrait of the family posing for the last time beside their dead relative. Moreover, it is a custom that the funereal portrait and the deceased’s corpse should be photographed together.The image produced, familiar to the close family but surprising for observers unfamiliar with the culture, is that of a dead person – a corpse – with the funeral portrait – a living person. Finally, the initial funereal portrait (that presented to the relatives during the wake) printed poster size, will be exposed later at the sides of the roads, more specifically among the Anglo-Ewe in Ghana’s Volta region, announcing anniversaries and commemorations of the death, but above all displayed as a”celebration of life” as we were informed by many posters in English.

C. Angelo Micheli

C. Angelo Micheli is a historian of African art. This text appeared in the first edition of the journal Transbordeur.

Transbordeur – Photographie, histoire, société

Numéro 1 – Dossier « Musées de photographies documentaires »

Edited by Estelle Sohier, Olivier Lugon et Anne Lacoste

Published by Editions Macula

236 pages

29.00 €