Passing on the Torch

The number of photographers represented in Africa State of Mind comes close to the number of countries, fifty four, that make up the continent. When so many African artists turn their lenses on rapidly changing societies freighted with histories of colonialism, expect to find diversity and diffraction in their multiplicity of responses.

The photographs have mostly been taken over the last decade and what they effect is a conscious decoupling from the hackneyed visual tropes that for so long have characterized representations of Africa. The result is a celebratory affection for everyday life that does not ignore contested issues of the past and present. The Western gaze that has been turned upon the continent, occupying ground somewhere between the voyeuristic and the anthropological, is explored and undermined by a number of the artists.

The first of the book’s four sections, ‘Hybrid Cities’, has an empirical foundation: by the end of this decade, over half of all Africans will live in urban areas. Girma Berta, on the street in his country’s capital, Addis Ababa, responds by isolating individual figures. He strips away the contextual background, presenting them as beings isolated in moments of their existence. The only backdrop is provided by a sea of warm colours, providing an affective resonance that would be absent if the quotidian, relational world – other people, buildings, traffic, whatever – was allowed to intrude.

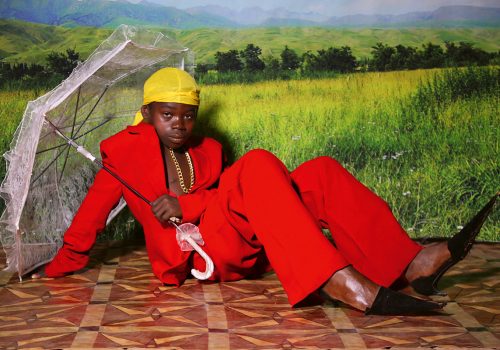

The ‘Zones of Freedom’ section covers photographers who challenge community policed notions of sexual identity and advertising-fuelled images of selfhood. Jodi Bieber, for example, reacts to a news report about anorexia affecting South African women who prefer Western norms of slimness to once culturally acceptable full-figured body shapes. Hassan Hajja in Morocco relishes explosions of colour and appearance that detonate received images, as in a group shot of women sitting aside scooters and clad in ebulliently patterned ankle-length abayas.

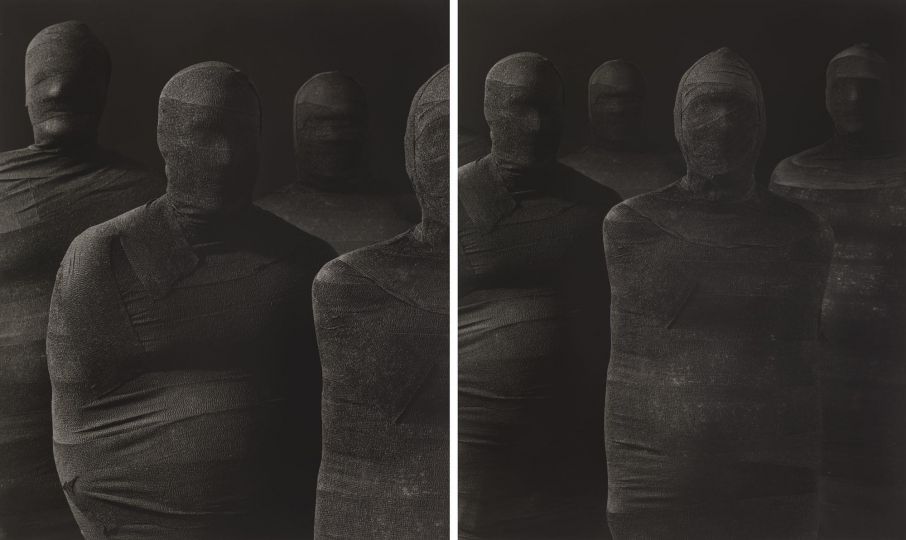

Colliding images also feature in the ‘Myth and Memory’ section, consisting as it does of subversive engagements with Western imagery and colonial legacies. A traditional semiotic is questioned when masks associated with ritual appear on figures in modern dress; European paintings of African men and women are reinterpreted; safari-like scenes are incorporated into satires on autocratic rule. Mohau Modisakeng, born in Soweto in 1986, deals with apartheid’s heinous legacy: ‘Ultimately’, he says, ‘South Africa’s past affects the conditions under which people practice and experience culture today.’ In one of the haunting images from his Ditaola series, a white dove takes flight from a man holding a rifle across his shoulders. The weapon signifies the violence engendered by apartheid while the man’s expression and the dove in a misty cloud evoke mixed affects: remembrance, regret and hope for the redemption of ancestral social injustices.

Namsa Leuba looks at vodun (voodoo) in Benin – where 20% of people still follow its animist belief system – without the white man’s baggage that taints it as the incurably exotic Other. Similarly, Lina Iris Viktor uses tribal cosmologies, mythologies and textile culture to invest her Liberian heritage with depth and power. They are not in the business of salvaging the past but, like Modisakeng, redeeming it – the saying about tradition not being the preservation of ashes but the passing on of the torch comes to mind.

The final section of Africa State of Mind, ‘Inner Landscapes’, steers away from the nebulosity that the title might augur. As the editor Ekow Eshun says – and his commentaries on the artists and their projects are admirably informative – the photographs are not a paean to subjectivity but work ‘in search of an emphatic connection with the viewer.’

This search reaches a reflexive level with the self-portraits of Youssef Nabil who, returning to Cairo in 1999 after periods abroad, looks to himself for something out of reach. In one image, Nabil gazes across to the port city of Essaouira in Morocco and there are hints of estrangement in the picture – as if the city’s 18th-century walls keep him distant, positioned on the outside – and this is echoed in other shots where he stares across the Nile to Luxor or lays down amongst tree roots in Los Angeles, as if craving belongingness. To give Lacan’s neologism – extimacy (extimité) – a spatial sense, something external combines with something intimate: that is, ‘something strange to me, although it is the heart of me.’ This is not to attempt a psychoanalytic reading of Nabil’s self-portraits but it does point towards depths of meaning to be found in the rich array of visual signatures that make up Africa State of Mind.

Africa State of Mind, edited by Ekow Eshun, is published by Thames and Hudson