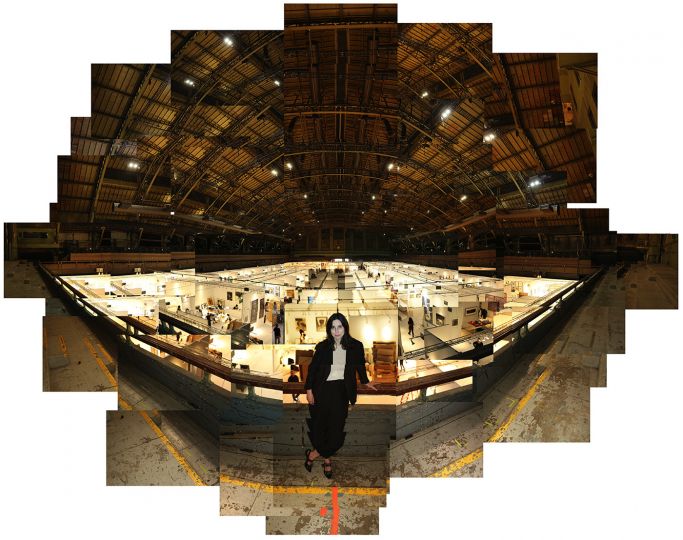

The exhibition ends soon. Thierry Grizard on his website Artefields made a beautiful presentation: here it is!

Sally Mann has an exhibition at the Jeu de Paume Museum since June 18, 2019. This is the largest retrospective devoted to the American photographer in France. It should be noted however that this set of photographs does not cover all the series of the artist. The exhibition focuses on Sally Mann’s relationship with the South of the United States, particularly Virginia, the birthplace and residence of the photographer. So there are absences or shortcuts, but the merit of this focus is to point to the heart of the work of Sally Mann.

Sally Mann, as she admitted at the opening conference of the exhibition “Thousand and One Passages” does not like to leave her Lexington property. She was born there, she married there, she lives there and never gets away from it long. Sally Mann has never been far from her birthplace for her photographic creations. She always insists on her attachment to southern light, hot, humid, thick. We can therefore say that the articulation of the exhibition is not only relevant but that it covers most of the corpus.

The land of Sally Mann

To say that Sally Mann is viscerally attached to her native Virginia is also to highlight one of the fundamental aspects of her work, namely memory and the intimate relationship to history.

Lexington and its surrounding area, which is close to Mann’s property, was one of the most tragic moments of the Civil War. The photographer has devoted a very important series of large formats wet collodion to: “Battelfields” (2001-2003). This series revisits the scene of clashes between the Union and the Confederates. Collodion glass photographs perfectly fit this part of the corpus. Indeed, as Sally Mann explains, glass photographs have an intrinsically spectral aspect, moreover they are subject to many imperfections that Sally Mann, unlike other photographers, strives to exaggerate.

When the American artist goes to the present scene of the fratricidal and bloody battles of the 19th century, she finds no trace of the brutality of history. An exact, naturalistic image would at best give only a documentary photograph marking oblivion at worst a bucolic image without great interest. Collodion-on-glass images in which the imperfections of the process of exposure to light are imparted in their chemical flesh give a kind of visual testimony to the passage of time. The image becomes a melancholic and tinged allegory of transcendentalism (see our article) where are revealed the absence, the oblivion, the death, the fragility of life and the overwhelming or reassuring permanence of the same light bathing the visible world . By this physical connection Sally Mann makes perceptible what is no longer. This is one of the great successes of this exhibition with a rather dark tone as it highlights Sally Mann’s awareness of the transience of family equilibriums as social, political and historical.

The “spectrality” of photography

Sally Mann, through her own apprehension of the South, works as a sort of documentalist. Through its melancholy, it documents balances in danger or loss, whether in childhood, peace or health, memory in its extended family dimension as its collective side. The exhibition at the Jeu de Paume museum is articulated mainly in so many moments of this transcendentalist memory and descriptions of the South.

First of all, there are battlefields pushed back in time, covered by the indifferent vivacity of Nature. Sally Mann gives life to these tragedies through a spectral evocation, it reappears metaphorically through the “stigmata” of collodion the ghosts of battlefields. Sometimes she goes as far as placing grains of dust on the development glass to simulate shooting stars, she invokes the spirits, the memory traces.

The exhibition continues in a subtle articulation between family and collective memory through the person of Gee-Gee, the African-American “nanny” who raised all Munger siblings including Sally. Sally Mann is from a generation of Virginian Americans who experienced segregation. So while the family was going to the restaurant, Gee-Gee stayed in the car waiting for them. Yet the photographer considered this woman as their adopted mother. She thus experienced the immense repression of segregationist racism that allowed black and white to live together in complete denial.

Much of Sally Mann’s work revolves around the relationship between personal memory and collective memory subject to historical and political tensions.

Sally Mann cleverly mixes the ingenuous memory of Gee-Gee, the painful awareness of the injustice and the memorial occultation of a good part of the social body and the spiritual experience of a kind of transcendent unity represented by the Nature, that is to say its vitality and one of its most striking manifestations for a photographer, the light, which from the past to today, from the intimate to the community, is the same and unique even though in perpetual becoming.

The photographic flesh

The exhibition hall dedicated to Larry and Emmett is probably from the point of view of memory and the most significant photographic “flesh”. In fact, we can see the large colloid prints of her schizophrenic son who committed suicide in 2016. The series “Faces” dates from 2004, but in the effacement of the faces of her children, including Emmett , already can be seen the meticulous attention of a mother as the experience of their distance as adults and the fear of their disappearance. The series “Faces” is in a way the acme of the approach of Sally Mann insofar as it combines the intimist testimony of the series “Immediate Family”, the memory effort in the form of spectral evocations of the past ( Battlefields, Southern Landscapes) or what is about to be, and the sensual expression, inspired in part by Cy Towmbly’s photographic work of a diffuse form of spirituality tributary of .Ermerson’s transcendentalism.

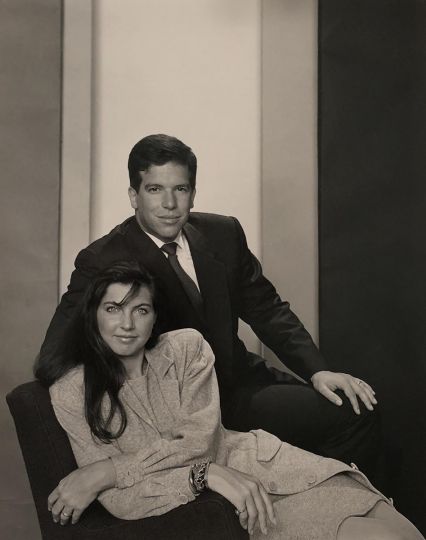

In this room we also see prints of the series “Proud Flesh” which reflects the spectacle of the disease. Sally Mann’s husband, Larry, at the request of his wife has agreed to pose and expose the harms of the muscular dystrophy of which he is a victim. The photographer gives a transcended vision, showing the bodily disorganization and mental strength of Larry. Here again the use of development on glass can mark the sensitive surface itself, that the American artist does not hesitate to scrape drips or sprinkle with traces of dust. Sally Mann’s post-pictorialism is therefore only formal, it is a technical means of increasing the perception of what is not visible.

This is how we can also see in this room the rare self-portraits, (beautiful ambrotypes), of Sally Mann. Following a horse accident she could no longer easily manipulate her huge camera Sally Mann takes herself has as a model. But what the artist wants above all is to bear witness to the suffering and the distressing spectacle of a body that escapes the control of the person who lives in it.

Sally Mann. Mille et un passages

Musée du Jeu de Paume

Through September 22nd, 2019

Curators : Sarah Greenough and Sarah Kennel