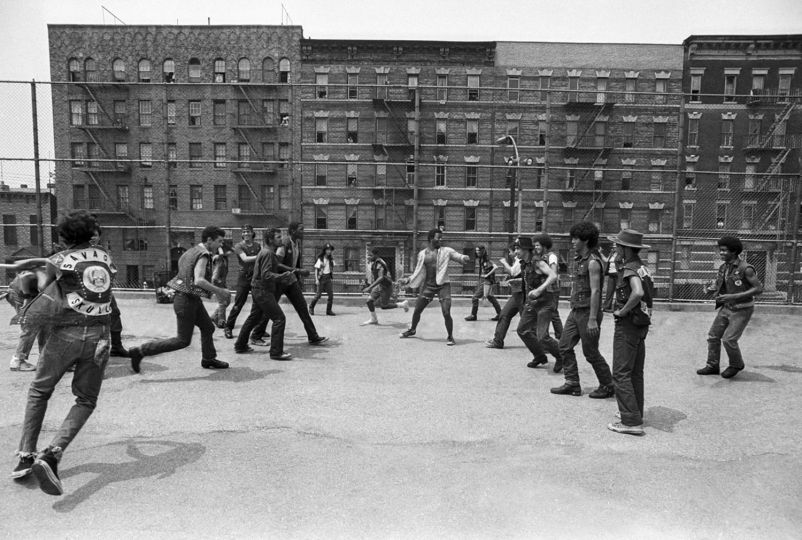

In the aftermath of this terrible conflict, there was an unquenchable thirst for information and images in France. The press was expanding and now the number of newspapers and magazines mushroomed. In Paris alone, no less than thirty-four dailies were on sale. The major illustrators and reporters of the pre-war period reappeared and, with them, their humanist style and an optimism and lyricism that continued to focus on popular life and the working-class districts. “The liberation had no sooner taken place than I returned feverishly to the only profession I had ever loved.“

Doisneau later wrote. And his life became ever busier as increasing numbers of reportages were commissioned by the many publications with which he collaborated; his personal situation left him little choice but to accept. His second daughter, Francine Deroudille, noted that in 1945 alone he created reportages on clandestine printers, the Aubusson tapestry manufacture, daily life at Renault, the Cirque d’Hiver, the Bobin cleaning company in Montrouge, Parisian concierges, the first vote for women on April 29, the capitulation of Nazi Germany on May 8, the miners of Lens, took portraits of Blaise Cendrars in Aix-en-Provence, reported on the premiere of Jean Giraudoux’s La Folle de Chaillot at the Théatre de l’Athénée, photographed Le Corbusier in his own home and the “Théatre de la mode” (an exhibition of mannequins dressed by leading French couturiers), and shot a paean of praise to liberated Alsace! Not to mention book illustrations and the much more remunerative publicity shoots.

His work with the press became ever more intense as it caught the attention of the media. We have already mentioned the magazine Le Point, edited by Pierre Betz, which employed him regulary for more than a decade, between 1945 and 1960, a period in which he contributed to some ten or more issues. The Communist weekly Action, edited by Pierre Courtade, absorbed a large part of his production over many years. He also worked intermittently for the magazine Regards, which sent him to Yugoslavia. But Doisneau’s most regular appearances were in La Vie Ouvriere (Working-class life). the magazine published by the French trade union Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT). He loved this contact with the world of the working class and praised its nobility without a partisan political tendency. “There is an entire world to discover.

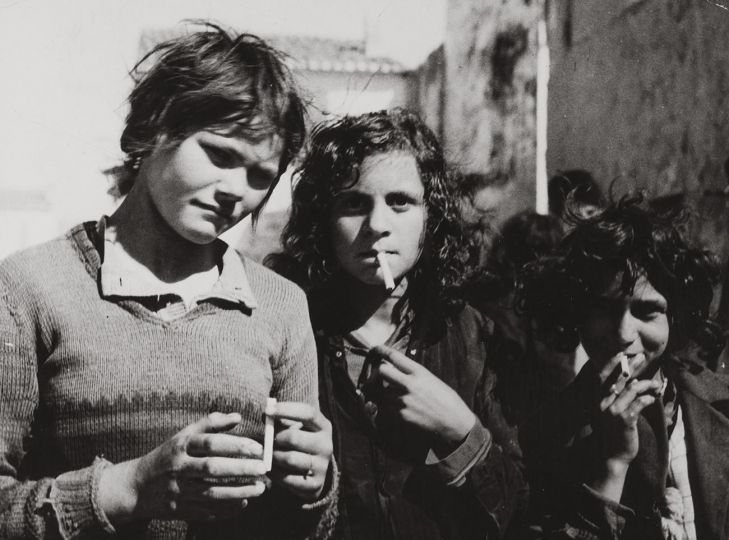

People use to the classic magazine news never hear about that. But it is in the world of work that one encounters the greatest fraternity and joy; despite the repugnant backdrop of the factory; It seems to me that people’s beauty stands out all the more strongly. 24 The magnificent portraits of the miners of Lens, made in 1945 for Regards, bear witness to the men’s serenity; nobility; and inner strength. Though loyal to certain titles, he was also publishing photos in many family magazines such as La Vie catholique illustrée, Femmes françaises, Clair Foyer, Sillage, Vie et Santé, and, above all, the great weeklies such as Realites, Life, Caracteres, Fortune and Picture Post. A special favorite was Point de Vue -Images du Monde, an illustrated current-affairs magazine edited by Albert Plecy.

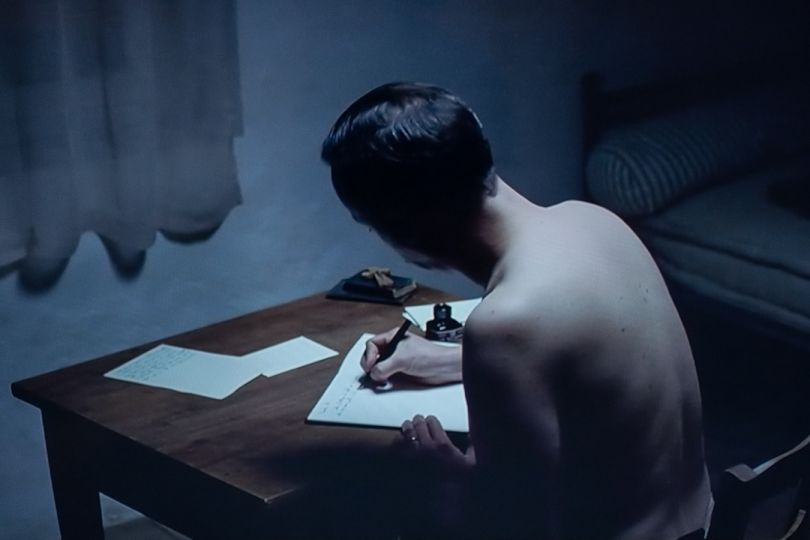

Active as he was, he nevertheless “stole” time from his employers to glean a few personal images during his travels and, above all, to take numerous pictures in his favorite suburbs. His method consisted largely of patience – “waiting for the miracle.” “I took mischievous pleasure in bringing to light anything abandoned, not just among people but also in my choice of backgrounds … ” “In the banal environment to which I belong, it some-times

happened that I perceived fragments of time in which the daily universe seemed to become weightless. Revealing these moments

might take one a whole lifetime.”

At that stage, however, no one was interested in these images. Even Raymond Grosset, manager of the Rapho agency that Doisneau was soon to join, showed little enthusiasm: “Don’t waste your time on this suburban busines . it hurts me to see you doing things like that. Your suburbs are gloomy and you expect me to sell people gloom?”.

In 1946, Doisneau’s friend Ergy Landau told him about the advent of the Rapho agency; the new name for Rado Photos. It quickly attracted a number of photographers such as Brassaï, Nora Dumas, Willy Ronis, Sabine Weiss. and Emile Savitry. “Finally someone channelled my abilities into practical achievements. Thus began a collaboration that has lasted till this day, when I’m one of the agency’s glossiest monuments. Looks like a lucky encounter from where I’m standing. I don’t know what he thinks of it”. A Loyal friend. Doisneau remained one of the agency’s major assets till his death.

Robert Doisneau’s life was a succesion of encounters, each more fortunate than the last. One of the first was with Blaise Cendrars. Maximilien Vox publisher at Denoel remembered the portrait of scientists that Doisneau had made in 1942 and suggested that he go and photograph the writer at the latter’s home in Aix-en-Provence. Cendrars had a reputation of being a lone wolf but the contact was immediate. By chance, they began talking about the writer’s childhood, which had similarly unfolded in the zone.

Doisneau revealed that he, too, was a zonard and offered to send him a few of the photos that he had taken there: “Talking about Kremlin-Bicetre and Villejuif hill seems a lot less banal on the terrace of a cafe on the cours Mirabeau in Aix-en-Provence … Cendrars liked my rough-cast hotos. He told me … “we’re going to make a book.”

Cendrars himself found a publisher, Seghers, and decided the layout of the volume. This ‘”as the beginning of a collaboration and exchange of letters that lasted until 1949, when La Banlieue de Paris was published: 152 images closely married to a text that Doisneau described as “dazzling. Its quite simple, I had to have two goes at reading it because it moved me so much.”

The volume summarized fifteen years of Doisneau’s disorderly harvesting of the “values not listed on the stock market, elements hitherto considered negligible,” into a sequence that had a power all its own. Though Louis Aragon had deemed the images -populist,” Cendrars was immediately struck by these unique antiacademic photos. “This book on the suburbs,” Doisneau later said, -is my self-portrait. Like them, I am compounded of dross.”

“For Cendrars, the suburbs were a dump. He had not an ounce of sympathy for ugliness. For me, it was the opposite: they were a reservoir of strenght and light. I didn’t want to clean them up completely in my images. I found Gentilly very ugly and absurd. But I liked the people, I thought they deserved a better environment…”. La Banlieue de Paris in the course of time became a bibliographical rarity and was republished by Denoel in 1983.