To mark the centenary of Irving Penn’s birth, The Metropolitan Museum of Art has open its doors in April to a major exhibition celebrating one of the foremost photographers of our time. With more than 200 prints on display (the majority a recent gift to the museum from The Irving Penn Foundation), the retrospective is the most substantial to date and explores every period in Penn’s prolific 70-year long career. From New York the exhibition will then travel internationally with a first stop at the Grand Palais in Paris in September.

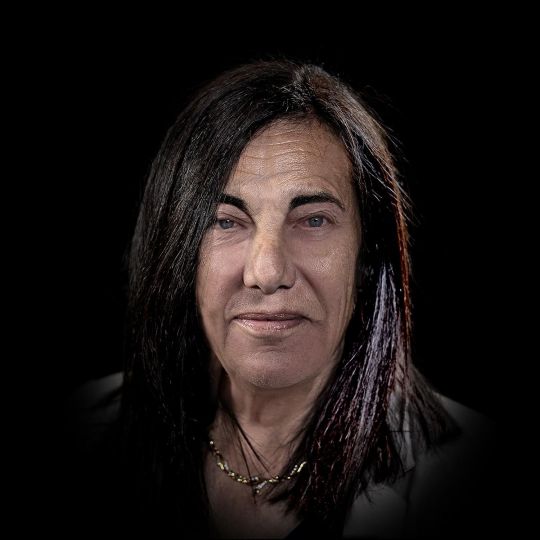

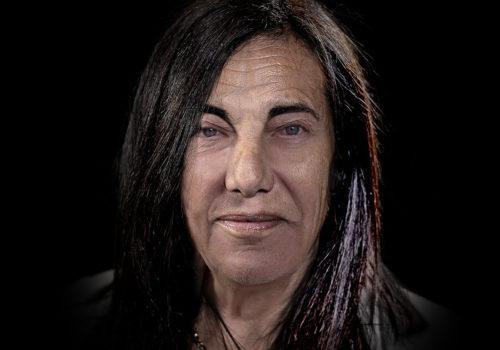

The publication of the accompanying book Irving Penn: Centennial is an occasion in itself. Not only does it feature the largest selection of Penn photographs ever compiled, including works that have never been published, it also provides essays with a fresh intellectual understanding of the deeply private artist and the human being behind the masterful photographs. The book and exhibition are created and co-organized by Maria Morris Hambourg, who founded the Met’s Department of Photographs in 1992 and knew Penn personally, and Jeff L. Rosenheim, the department’s current Curator in Charge.

The two curators were asked to select three images each from the exhibition and reflect upon them with Luncheon magazine’s editor in chief and creative director Thomas Persson. The interviews provide fascinating insight into the artistic creation and circumstances in which these photographs were made. From Marlene Dietrich to a tribesman in New Guinea; a female nude and a still life for Vogue; a fishmonger in London and two cigarette butts – Penn’s wide-ranging subjects were all part of his worldly narrative and, as they are observed within these pages, his profound talent for storytelling.

Today, we present the first part of this series with words on Marlene Dietrich, New York, 1948.

Thomas Persson: Marlene Dietrich, who maintained her image with painstaking precision, knew many things about photography and was known for directing photographers, telling them how to take her picture. But that was not the case in this portrait by Irving Penn. What do we know about this sitting? What happened on set?

Maria Morris Hambourg: Penn was not into flattery. His job at that moment was to make portraits that would stop traffic in the pages of the magazine. He wanted psychological impact and graphic punch. With Dietrich he obviously had an idea that included ignoring whatever she had on. Penn recounted that the minute she walked into the studio she told him precisely where to put the light. He paused, and countered, ‘Now look: In this experience you be Dietrich and I’ll be the photographer.’ Her response? ‘Boy, she boiled, but she stayed with it,’ Penn said. She had met her match. Instead of presenting her as the vamp, seductive and available, Penn cocooned her. She is mysteriously inviting, yet cloaked. Her beautiful face peers from atop a sort of chrysalis; it’s surprising, it’s economical — it’s quintessential Penn.

Thomas Persson: Irving Penn’s sets from the late 1940s, the narrow corners and old carpets, are now iconic. But they were invented for other reasons than simply being aesthetically interesting, and this at a time when Penn was only beginning to take portraits. How did he come to use these components?

Maria Morris Hambourg: Penn started out moving things around on the tabletop; he was essentially a great still-life photographer. When he had mastered that, [Alexander] Liberman, his editor, pushed him into making portraits. Initially Penn admitted he was ‘really not completely comfortable taking pictures of people.’ The angled stage flats were a way to orchestrate a more level playing field. When a big illustrious personality walks into the studio, what are you going to do with them? Penn told me, ‘I needed to contain them.’ He had to figure out a protocol: first he would get to know them a bit over coffee, watching them within a normal conversational give and take, and while he did that, he would form an idea for the pose. Then they would go to the set, and he would work with them there.

Thomas Persson: Penn explained that there was an element of sport or personal contest in these early sittings…

Maria Morris Hambourg: Those sessions were surely something of a joust. In the late forties Penn wasn’t famous yet, but he was employed by Condé Nast, one of the most powerful publishing empires in the western world. He had an upper hand not only in that sense but he also had the machine, the implacable camera. The celebrity, on the other hand, was famous and accomplished; they had their armour, the face they had prepared to meet him, and a certain idea of how they wanted to appear. Naturally there was push and pull, a negotiation between the two sides. In that regard, Penn talked about baseball, how he loved the idea of a pre- ordained playing field and the variable action that would take place there. The play is always unknown. What happens on the set is also unknown. It’s a very demanding dance — nuanced, electric, focused, and exhausting. Penn was patience itself and his sessions often went long. He was like a master poker player; as Avedon said, he ‘sits it out.’

Thomas Persson: He photographed hundreds of the most influential cultural personalities of the period. With their stark modernity and human intensity, these early portraits were given top positioning in Vogue and really made Penn’s name. By 1950 he had become famous…

Maria Morris Hambourg: Yes, he took some 300 plus portraits of an extraordinary range of personalities in just two years (1946–48). In that post-war moment, New York was brimming with talent, and the magazine’s editors reined it in. One didn’t refuse an invitation to be photographed for Vogue. Similarly, when Penn went to Paris in 1948, the celebrities he photographed were acquaintances of the young Vogue editor, (the late) Edmonde Charles- Roux. But by 1950, notice had been taken of Penn’s still lifes, portraits, and fashion work. When he did the Collections with Lisa Fonssagrives as the main model in 1950, those pictures, and the first of the Small Trades images, sealed his mastery. It had all come together by 1950.

Thomas Persson is the editor in chief and creative director of Luncheon. Maria Morris Hambourg is the founding curator of the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York.

Irving Penn : Centennial

April 24 to July 30, 2017

The Met, Gallery 199

1000 5th Ave

New York, NY 10028

USA