The Byrd Williams Collection at the University of North Texas contains more than 10,000 prints and 300,000 negatives, accumulated by four generations of Texas photographers, all named Byrd Moore Williams. Beginning in the 1880s in Gainesville, the four Byrds photographed customers in their studios, urban landscapes, crime scenes, Pancho Villa’s soldiers, televangelists, and whatever aroused their unpredictable and wide-ranging curiosity.

With their recent acquisition of the Byrd Williams Family Photography Collection, the University of North Texas Libraries have begun a sizable undertaking. Containing prints in the tens of thousands, negatives numbering nearly a third of a million, and a small multitude of manuscripts and artifacts, the collection represents a formidable commitment to over a century of history in Texas and beyond. As well, it is also an all but unrivalled holding of that rara avis in the modern history of the medium—an extensive, multi-generational archive of a dynasty of photographers.

It is no less than an archive of four direct generations of fathers and sons who have shared both a common family name, Byrd Williams, as well as a passionate interest in and continuing commitment to photography. It is a fascinating record of imagery and interests, amassed over more than a century, and retained and cared for over these past decades by the final photographer in this tribe’s lineage, Byrd Williams IV. Indeed, before the collection made its long trek to the University of North Texas, Byrd IV has overseen its careful storage and movement through at least eighteen different venues—a variety of homes, garages, offices, closets, spare rooms, warehouses, studios and rental spaces. While this is not a unique example of any collection’s genealogy, it does reflect the passionate commitment that Byrd IV has always held to his progenitors’ saga, as well as the remarkable journey that an archive can take on its way to a final institutional sanctuary.

Having had the privilege to examine much of this collected material, I can attest to the richness of their contents and the scholarly potential of the more than 120 years of imagery and information that this archive contains. From its initial, tentative photographic commitments in the final decades of the nineteenth century through to the whirlwind of informed, artistic imagery that Byrd IV still creates, the family collection also can tell us much about the cultural, social, and technological transformation of both this state and this nation throughout the twentieth century and beyond.

From its beginnings with Byrd Moore Williams, Sr., in the 1880s, the collection may seem to contain only the “stuff” that other American families have amassed over time and generations. With the rise of the roll film cameras during this period and the subsequent popularization of family photography that it heralded, Byrd Sr. (Byrd I) was only one among many other Texans who purchased an affordable hand camera, loaded it with roll film, pushed the button, and let Kodak do the rest. Far from being the first major Texas photographer, nor in fact even a photographer at all except in the general amateur sense, Byrd I was a merchant who settled in Gainesville—in every sense small-town Texas—opening a store on the town square that sold dry goods, hardware, and even cameras. It would seem a rather slight beginning for the progenitor of a photographic dynasty.

Still there was something about photography that must have struck a chord with Byrd I. Before the century had turned he was using his early Kodak for snapshots of his personal life and family as well as eventually processing prints in the darkroom that he had constructed in his home. Moreover, he helped to introduce photography into his community, not only through the sales of early hand cameras but also by marketing in his general store such early photographic formats as stereo views and the increasingly popular photographic postcard. In fact, some of the postcards that he sold incorporated his own imagery of the town, people at work in farm and field, and scenes of different sites around the state. As with other pioneers who foresaw the commercial potential of this relatively new medium, Byrd I was able by both practice and promotion to foster a growing appreciation for photography’s influence within the generations; one that would, in the words of Willa Cather, “bring to the old, memories, and to the young, dreams.”

While Byrd Williams, Jr., (Byrd II) would pursue very separate dreams, leave the state for many years, and chase along various career paths before becoming a professional engineer, he must have experienced to some significant degree his father’s fascination with the medium. Judging by the surviving output of his image making, he practiced photography often and even brought the camera into the documentary dimensions of his own work. His prints—either commercially-processed or hand printed in that same, popular postcard format that he learned from Byrd I—reveal that he used a variety of box and folding cameras of that era in support of his industrial photography. He carried the apparatus with him on his many travels around the early twentieth century American West and Mexico, recording in those decades excavation and building projects, workers at these various sites, and scenes of harbors and ships—as well as his favorite subject, landscapes.

Within Byrd II’s landscape postcards (including some fine views of Yosemite before it became Ansel Adams’s primary domain) one can find a finely developed eye for framing and exposure. In addition, there is often a certain confident freedom of expression in his many personal snapshots. A number of his groupings of friends and family are natural and seemingly effortless, revealing both an ease with the camera and an affable gregariousness that worked well with many of his subjects. You see it in such works as the threesome of friends which he chose to pose on a ladder. It is also there in the variety of poses that are struck by the three West Texas squirrel hunters standing over their tiny kill with a certain curious solemnity. The camera often proved to be a spontaneous extension of Byrd II’s vision and, by bringing it along in his work and making it a part of his daily life, he frequently proved able to call upon his natural instincts to contribute effectively to his resultant imagery.

It remained for his son, Byrd III, to make the momentous leap to pursue a full, professional career in commercial photography. With his establishment of a completely equipped studio in Fort Worth, Texas, he would maintain a successful business with expanded equipment and a large calendar of jobs that covered a great variety of clients and projects. Combining his strong sense of organization, native hustle, hard work, long hours, and a keen sense for the business, Byrd III fully embodied the qualities of a successful, mid-twentieth century professional photographer.

However, there was something more ticking away in Byrd III’s character, something beyond the customary familial dedication to photography that his father and grandfather had nurtured. Byrd III would later refer to himself as “an observer of life,” a conscientious quality he would reinforce through his photography. Certainly his clientele provided him with multiple challenges ranging from portraiture to the documentation of many cultural events and social organizations. His work books and portfolios include an immense variety of photographs: of performers and celebrities, of sports and recreation, and of a broad range of places including offices, industries, department stores, train stations and even public restrooms.

Moreover, Byrd III also amplified the family habit of carrying his cameras everywhere, into the streets and businesses of mid-twentieth century Fort Worth, recording the people and places of a vibrant downtown and its expanding suburbs while revealing much about the lives of its people at work and at play. Whether or not he ever considered himself a true documentarian, he brought to this everyday avocation the same precise eye and fierce dedication that he utilized daily in his commercial work. Byrd III also paid attention to the growth of professional and artistic photography, and some of his work shows the evident influence of and experimentation with European Modernism as well as the “decisive moment” style of Henri Cartier-Bresson. There is even a small series of his wife washing her hair over the sink that has all the intimacy and elegance of some of the works of future continental Neorealists. What he chose to observe ranged from building construction to street incidents, and from views of the city at night to such ahead-of-its-time projects as an entire series showing women at work in the 1950s. And, perhaps most critically, he also inspired his son to follow him into the photographic life.

While learning much both technically and inspirationally from his father, Byrd IV expanded his passion for the history of art and culture into a full career as artist and educator—the practical and professional direction of many of his contemporaneous photographers of this previous generation. While the Williams family’s dedication for the medium undoubtedly played its part, of course, Byrd IV’s success came from such equal dimensions as his own unique eye, his scholarship, his dedication to learning, and his respect for the role that all history continued to play in his own artistic evolution.

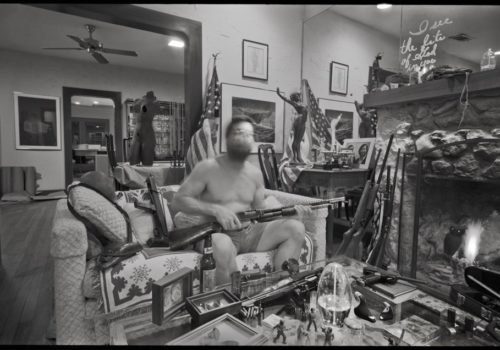

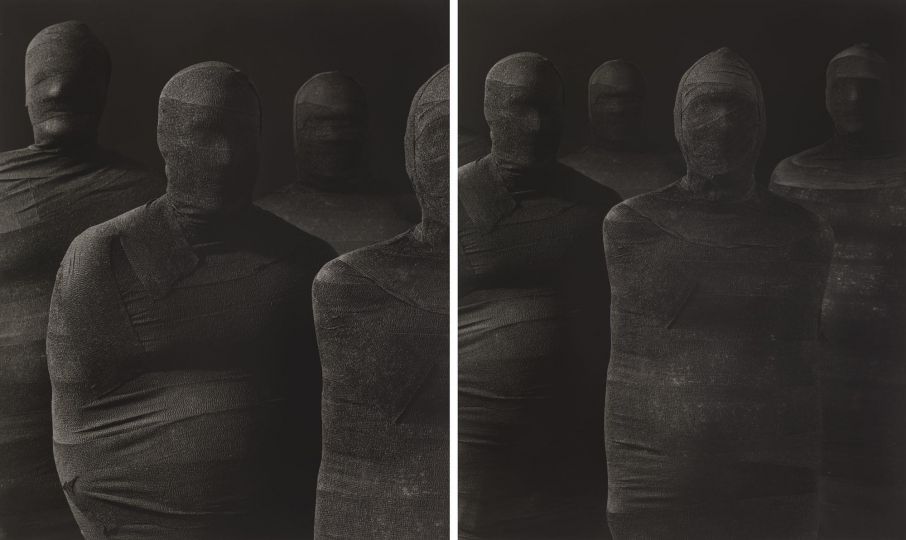

One can apprise Byrd IV’s art as a culmination of sorts—equally challenged by conceptual theory and by his photodocumentary heritage. As is typical of many of photography’s finer artist-educators, his imagery combines a richness of technique with an expansive variety of styles and self-challenges—all of which the good teacher tries to pass on to his students. In terms of his project orientation he has covered a number of various topics, from television evangelists to a lifelong study of violence in society. In other instances he has returned to a range of interior spaces and public places, much like his father before him, but deliberately choosing to explore, map out and interpret them in a wide range of styles as well as in both black & white and color. Perhaps there is much to the old Sanskrit saying about fathers living on after their deaths in their sons, for photography seems to weave its way like one bright thread through the tapestry of the Byrd family’s lives. If so however, it is good to know that Byrd IV continues to build upon this familial influence—and hopefully its inspiration—while mentoring an ever-growing generation of students as well.

Unlike other photographic archives that have come out of this state, you will not find a whole mess of cowboy and cattle imagery in the Byrd Williams Family Collection. Indeed, the vast majority of photographs included therein transcend the romanticized tropes and misconceptions of what many others choose to call “Texas photography.” While the Byrds may have started their photography in the regional home and later the studio, they incessantly also headed out the door and into the world with their cameras in tow. By and large the Byrds, starting with Texas, have always used those cameras to both document and interpret an expanding world view throughout the past 120+ years. (One could even consider a Texas-sized brag: that with Byrd IV’s continuing career the family has now entered a third century of image-making.) Their photographs extend far beyond their subjects to include their own independent concerns or interests. Consider the countless varieties, from Byrd I’s views of his own general store in Gainesville, to Byrd II’s landscape postcards of the American West, throughout the diversity of Byrd III’s street scenes or commercial jobs, and now with Byrd IV’s ever-expanding, global range of both documentary and conceptual undertakings. No, what you will discover—what often occurs in the strongest regional-based archives of the best photographers—is a serious affiliation to place combined with an inherent faithfulness to witness in a more universal manner the people and the cultural change that have transformed that place.

If, as Rebecca Solnit suggests, a “path is a prior interpretation of the best way to traverse a landscape,” then one may rightly conclude that Byrd IV’s life has been subsumed by finding and preserving the paths of his family throughout history while simultaneously continuing to blaze many more of his own. Indeed, his vision reflects both a dedication to the record of the past (he has even rephotographed a number of Byrd III’s street views) as well as an ease with experimentation and innovation. The traditions of a person’s past can find no greater freedom than in their acceptance of the weight of the present to help define their belief in the future. It is the sterling quality that runs throughout Byrd IV’s work, but just perhaps it is also there in the lives of the earlier Byrds too. Ray Bradbury, as usual, says it much better: “Everyone must leave something behind when he dies,… A child or a book or a painting or a house or a wall built or a pair of shoes made. Or a garden planted. Something your hand touched some way so your soul has somewhere to go when you die, and when people look at that tree or that flower you planted, you’re there.”

In compiling this volume Byrd IV has drawn a number of comparisons between the imagery of all the Byrds, utilizing contrasting pages for the juxtapositions of subjects, genres, projects, themes and styles. The process is a fascinating one—in part because it invites us to closely study the images and make our own assessments and comparisons, but also because it demonstrates the power that photography held for these fathers and sons. All of the Byrds, despite the differences in their career choices and the cultural and technological changes between their eras, came to photography as young men and continued to have it play significant albeit disparate roles in their lives. The universal arc that the photograph has played through humankind in the past two centuries—indeed, continues to play today—may ultimately be incalculable. But to bring its focus down more, to witness its resounding impact on and throughout these four generations of one family—just maybe this can offer us a human-scaled framework by which we can better attempt to understand the transformative and lasting power of the camera arts.

As the Byrds shaped their photographs, so photography shaped the Byrds in turn. And now, also in turn, the photographs in their archive may continue to shape all who now share in the future experience of seeing their works anew. It is part of the age-old tradition, be it the familial custom of handing down something intimate and personal, or the universal commitment of history to try to better all of humankind. May photography’s one bright thread continue to weave its way through all our lives. For, with each photograph that can be preserved and not allowed to slip into obscurity a promise can be kept, not just to preserve the true elements of the past but also to add good substance and honest meaning to our present and our future.

Roy Flukinger

Roy Flukinger is a Senior Research Curator, Reader and Viewer Services at The University of Texas in Austin.

Proof: Photographs from Four Generations of a Texas Family

Byrd M. Williams IV

Published by UNT Press

$39.95