In early 2020, to celebrate the 10th anniversary of FotoEvidence, I interviewed founder Svetlana Bachevanova. At the time, I asked her what the next 10 years might look like. “I am always working on crazy ideas and thinking of new collaborations,” she’d laughed. “Let’s see where we might go from here.”

Less than 12 months later, the FotoEvidence Foundation made its official debut in January 2021 in France. The new Foundation is headed up by co-presidents Peter Bouckaert, the former Emergencies Director of Human Rights Watch and Darcy Padilla, who is renowned for her long-term social documentary photography. Bachevanova is of course involved in the Foundation and continues her role as the publisher of FotoEvidence.

I spoke to Bouckaert about his hopes for the Foundation, and how his association with FotoEvidence unites his passion for photography, journalism and human rights activism.

Bouckaert’s involvement in the human rights movement was initially sparked by the atrocities of the Rwandan genocide and the Balkans Wars in the 1990s when he was at university. Studying law at Stanford in the US, Bouckaert became an anti-apartheid activist and for a time worked with Nelson Mandela’s lawyer George Bizos in South Africa helping to draft the Truth and Reconciliation Commission legislation.

In 1997 Bouckaert joined Human Rights Watch (HRW). His first field trip was to Uganda to investigate the atrocities perpetuated by the Lord’s Resistance Army. “I was just fresh out of law school and confronted by these 14 and 15-year-old kids that had been abducted from their homes, and who were forced to be involved in some of the worst atrocities I have ever had to document. It was quite a shock to move from law school to the field and be confronted with such horror.”

Yet Bouckaert was resolute to stay the course and worked tirelessly for HRW for 20 years. During that time, he covered some of the most appalling human rights abuses and tragically lost colleagues to conflict and barbarism, but it was only after the Rohingya genocide in 2017 that he stepped back from the frontline.

“I just felt completely overwhelmed by all the trauma I was documenting. I also felt very disempowered. In just a few months, the Burmese army burned hundreds of thousands of people out of their homes. There were so many massacres. Standing at the border seeing people flow across telling you these horrific stories, I just felt powerless.”

Leaving HRW gave Bouckaert the opportunity to get involved in “healing work.” He is now engaged with two youth empowerment projects, one in London and the other in Madagascar where he lives. Taking up the co-chair for the FotoEvidence Foundation allows Bouckaert to continue to agitate for change, and to be involved in visual storytelling which he believes is crucial to affecting change.

“In 10 years FotoEvidence has done some incredible work to make a very significant impact. We can use what we’ve learned to accelerate change and engage more broadly. Taking the picture is only the first step. It’s not enough just to shine the light, we have to get these images in front of the right eyes. We have to build our audience and also reach the younger generation. That means embracing the world of digital media, making our books more accessible, engaging in conversations on social media, and finding creative ways to achieve the impact we desire.”

Photography and Human Rights Activism

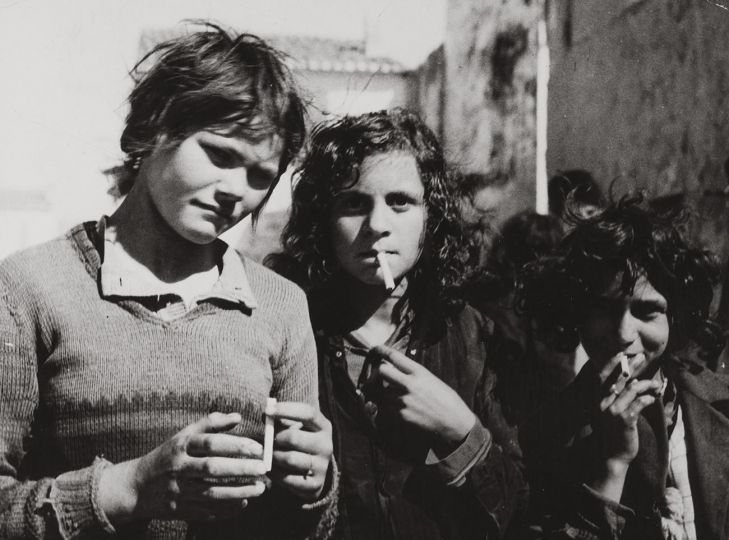

In the nascent years of his career as an activist, Bouckaert identified that the human rights movement needed to move away from its legalese and “adopt some of the tools of journalism and photography” in order to engage with the wider community.

“Visual storytelling has been a very big part of my work since the very beginning. The only way people will become really outraged about what’s happening in a remote place is if they can identify with the people affected by these human rights abuses and crimes against humanity. They’re not really going to care immediately about the legal context in which these abuses are taking place. But they may care about the mother who lost her son, or the family who’s been burned out of their home.”

In 2013 he teamed up with award-winning photojournalist Marcus Bleasdale to raise awareness of the unknown conflict in the Central African Republic (CAR), and ultimately, to get a UN peacekeeping force deployed there. This work became The Unravelling: Central African Republic which won the 2015 FotoEvidence Book Award. It also heralded the beginning of Bouckaert’s collaboration with Bachevanova and subsequently he’s written essays for books by Fabio Bucciarelli and Patrick Brown.

“It was a great honour to get the CAR work, that probably wouldn’t ever have been published anywhere else, published by FotoEvidence,” says Bouckaert. “I think that’s really the value that FotoEvidence brings to the world of photography. They take the work of people working on often unpopular or difficult social justice issues, and they give it the recognition it deserves. There are very few other outlets for this kind of work.”

With his legal grounding, it is not surprising that Bouckaert’s staunch belief in the photograph as a conduit for social change is evidenced based. When he was in CAR, he posted to Twitter one of Bleasdale’s photographs depicting a young boy who was literally starving. “Within a few hours, I had a phone call from the Office of the UN Secretary General, asking me what was happening with this community and just a few days later, they were evacuated to safety. So, images matter. If I had just put up a Tweet describing in words what was happening in this camp, I would not have had that kind of response. Sadly, the boy died before they were evacuated but his image certainly drew the attention of many people.”

The response to this image also reinforces for Bouckaert the import of social media. “It took almost two years to build up an audience on social media of journalists, policymakers and individuals. It was journalists who republished our tweets in The New York Times. It was policymakers who took our images into the policy discussions about what to do about the Central African Republic, ultimately convincing President Obama to back a UN peacekeeping intervention. It was also ordinary people who retweeted our images, who were outraged about what was happening, and who helped us build the public pressure needed to get the world to act.”

Ever the pragmatist, Bouckaert is quick to point out that social media has its own problems, and it is not all peace and love in cyber space, yet it would be foolish to overlook the opportunity to reach such a diverse and large audience in real time.

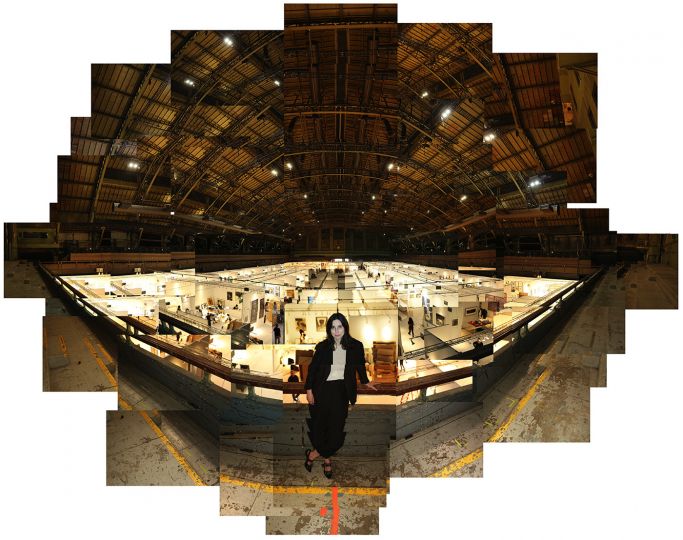

In Search of New audiences

Bouckaert acknowledges that the FotoEvidence audience, especially those at photography conferences and events, are not the ones that need convincing that these stories need to be told. “What’s really important for me, and also for FotoEvidence, is that we reach beyond the usual suspects to increase the social impact of the work of these photographers. We need to get in front of university students, to get in front of ordinary people, to get the images out in the street and on social media. Through the work of FotoEvidence, these photographers, who are also activists, can hopefully achieve the impact they seek.”

The FotoEvidence Foundation Board and Advisory Committee comprise professionals who are engaged in new and exciting ways to tell visual stories, “cutting-edge thinkers” says Bouckaert. Each person brings a unique perspective and experience to the Foundation. For instance, co-chair Darcy Padilla also teaches at university level in the US bringing important insights into how that space operates and the opportunities it presents.

“Universities are key if we are to engage young people,” observes Bouckaert. “But we need to think about the digital space too. People in their teens and twenties are accessing images very differently from older generations. I think engaging with the younger audience will help us strengthen FotoEvidence to make further impact.”

He anticipates engagement will be multi-directional and also involve communicating messages of hope, so that audiences don’t become despondent. “It’s very important that we don’t leave our audience with a feeling of despair. I think that when we are showing images of suffering and horror that we also need to offer a very clear way forward out of these horrific crises. There are always answers, there are always actions we can take to stop these atrocities, to rebuild peace, to stop the messages of hate and division, to bring about accountability.”

Bouckaert acknowledges that while “we have some great ideas and are highly motivated, we also have to find the money to actually make this happen. You know, nothing is free in this world. It does take donors and funders and it’s not always easy to find people willing to finance these difficult to look at stories. But I’m an optimist. If I can get people to care about the Central African Republic, a place they didn’t even know existed before we went there and took the images, I do believe that we can get people to mobilise behind FotoEvidence.”

Discover more about FotoEvidence.com