Though I buy books all year round, I find the holiday season is the ideal time to reflect upon the people who have influenced and inspired my life, the best and boldest and brightest hearts and minds to cross my path. Each of the people in my life brings something distinctive into the mix, whether it is a friend’s strength in the face of chronic illness or another’s courage to go off the beaten path in search of life’s purpose. To each of these people, I wish to share with them something from my heart, and more often than not, the gifts that best represent my spirit can be found in book form.

Perhaps this is because I love books more than any other medium. My love of the image and the printed word becomes a passion when I encounter the power of art and photography in book form. I remember at the tender age of ten, I made my first art book; actually I had written a series of different stories and thought it would look best with illustrations throughout. I remember even binding the book; I had drawn on tissue paper and used that to cover two sheets of cardboard. Then, I took three gold push pins and stuck them through the boards and sheets of my book. It didn’t hold together very well, but it did teach me a few lessons on the importance of production quality in any project.

Fast forward a couple of decades, and I have the distinct honor of reviewing photography books for La Lettre, which is a pleasant kind of irony, considering once upon a time it was I who was pitching journalists to cover books come holiday season. And so, by way of this introduction, I would like to introduce you to my new series of book reviews, focusing on the coming holiday season as I imagine that you, like me, will be considering what to give to your loved ones, wondering which object would best communicate the thoughts and feelings closest to your heart.

For my first holiday gift guide column, I have selected three books on fashion, a subject I rarely cover. Perhaps it is because, for me, fashion is something to wear, rather than to contemplate, though I understand both aspects of the medium easily. In selecting the titles for this column, I was most impressed by the way in which the book becomes the perfect vehicle to showcase the ideas of the fashion world.

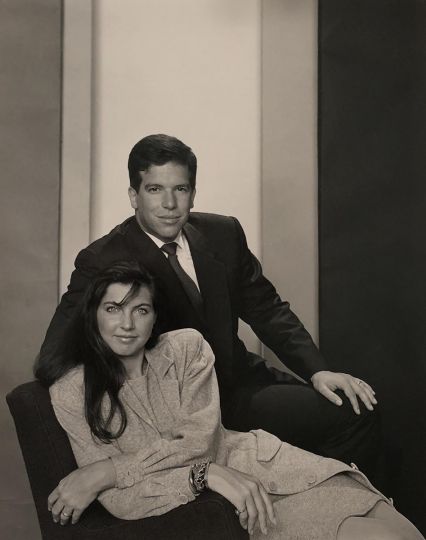

Nostalgia in Vogue: 2000–2010, edited by Eve MacSweeney (Rizzoli International Publications) does what illustrated books often do best—it acts as a timeless treasure trove, housing the best of the best of the best. Each chapter is drawn from Vogue’s Nostalgia column and offers a personal insight into the worlds of art, celebrity, and creativity, examining the way in which the visual medium of the fashion photograph speaks a language all its own.

As Anna Wintour explains in the foreword, “In each issue we invite writers, designers, photographers, and others to nominate a Vogue image—a portrait, fashion spread, still life, or interior’ that they remember and that in some cases literally changed the path of their lives. The results are often astonishingly vivid: Revisiting their chosen photographs jump-starts our columnists into remembering what they were doing and thinking and feeling the moment the picture first appeared.”

From here, great stories are born. Joan Didion reflects on a portrait of Tai Chi master Da Liu photographed by Irving Penn in 1962, writing, “Memory fades, and the full cast has vanished, but there was more going on than meets the eye in that studio facing Bryant Park. Penn, of course, was there. As the junior Vogue editor assigned to see the Tai chi spreads through to press, I was there. I do not remember either Da Liu or Mrs. Bertie Donnelly (in fact my uncorrected ‘memory’ of the occasion involved the entire New York City Ballet doing Tai Chi, a wishful reworking bearing no resemblance to any picture that seems actually have been taken)…”

As Didion notes, memory is a powerful—and priceless—thing. Nostalgia in Vogue allows us access into the minds and memories of artists and writers in a way that goes far beyond the discussion of fashion and takes us into the realm of art, culture, and history—both personal and collective. It is here that you can read about Edmund White’s love affair with postwar Paris; about Karl Lagerfeld’s intrigue with a Balenciaga dress photographed by Irving Penn; and of Patti Smith’s fascination with millinery and high society finery, among many other wonderful tales. Nostalgia in Vogue takes us back to times that rocked the collective unconscious and unearthed these gems, pearls of wisdom, diamonds in the sky, so much can come from one photograph, when it is in the right hands.

Indeed, the hands that hold photographs are often as important as the photographs themselves. And when those hands have the eyes of the world upon them, one person can change the direction in which we as a culture and society will go. One person with such immense power was Diana Vreeland, who was otherwise known as the “High Priestess of Fashion. “ With career highlights that includes fashion editor of Harper’s Bazaar (1936-1962), editor in chief of Vogue (1962-1971), and muse-in-residence at the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute (1972-1989), Vreeland is an American original.

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel by Lisa Immodino Vreeland (Abrams) chronicles fifty years of international fashion. Vreeland’s life and accomplishments are chronicled in chapters showcasing her professional triumphs, all born of a personal passion that kept her at the vanguard of an industry determined by shifting tastes and changing times. As Vreeland noted, “Passion for passion, you can learn anything, you can do anything, you can go anywhere. Don’t you think passion is very rare? And I think that it is getting rarer because there is so little around us.”

Undoubtedly, Vreeland’s passion was the flame that little countless others. Her work with photographers including Richard Avedon and Irving Penn defined an era and evolved with the times. Together, with the pages of Bazaar and Vogue laid open to these ingenious minds, a revolution in fashion took hold. As Bob Colacello explained, “I think that Diana was really almost the epitome of what New York was about. This melding of Europe and American and this acceptance or openness to everything that was new and different and wild.”

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel takes us into Vreeland’s world, providing a wonderfully documented look at her most iconic work. As a woman who understood not just fashion, but how to express its ideals, the photographs and stories collected here are a rare treat for the person who wants—needs—the inside story. The beauty of looking at her work collected together in one volume is to see how distinctively she applied her aesthetic in each arean of her professional life. In Bazaar, Vreeland’s quirky classicism maintained an old world charm. In Vogue, she set her eyes upon the world, interpreting the foreign elements of style and culture as part of a larger global landscape. And at the Costume Institute, she brought all of these together, setting the stage for a truly theatrical experience, where fashion came alive in three dimensions, more a form of sculpture and performance than anything else. Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel is the ultimate guide to one of America’s greatest arbiters. Why Don’t You…indeed!

Vogue: The Covers by Dodie Kazanjian (Abrams) is the final title in this triumvirate of American fashion books. Herre they are, from the 1890s until the present—truly an embarrassment of visual riches. In paging through this book, we see the ideal of Female as it evolves over time, changing in many ways but always keeping an eye towards beauty, style, grace, and distinction. Quite a challenge when one considers that models are meant to be mirros upon which we cast our fondest aspirations—they are to be Everywoman and the Ideal Woman at all times, so that we can seek her of her guidance to find the greatness within.

As Hamish Bowles writes in the foreword, the covers, “…held up a mirror to their times, as Vogue’s covers have continued to do so throughout the decades. As this book so delectably illustrates, those melting Dryden and Plank lovelies hardened into the brittle Jazz Age garçonnes of Lepape and Benito. These in turn developed gentle curves and a more three-dimensional aspect in the suave hands of Carl Erickson—then bloomed into full-color photography as Surrealist mavens or sportif sirens thanks to Horst P. Horst et al. They transmorgrified into Crawford-lipped patriots during the Second World War and then disappeared into their hothouses to emerge as absurdly laquered, wasp-waisted mid-century sophisticates. Diana Vreeland sent them into orbit, gave them individuality and kooky ‘pizzazz’ with an exclamation poiunt. Grace Mirabella gave them toothsome all-American good look, lip gloss, and statement earrings. Anna Wintour turned stars into models, models into stars, and continues to show us that it is all in the mix as she dresses them in T-shirts and ball gowns.”

For the first few decades, illustrations defined the look of he covers, creating a quaint charm that evokes nostalgia for a time before photography dominated the world’s view of itself. Come the 1930s, the photograph replaces the illustration as the cover image, though Vogue, or the framing of the model as the subject of a story, rather than the creation of the individual as icon. In the 40s, this begins to shift as photographers like Irving Penn, Horst P. Horst, Erwin Blumenfeld, and John Rawlings begin to showcase their work.

By the time the 50s arrive, Vogue has established a solid photographic identity. It is both in keeping with and leading the time, representing the ideal American woman as a creature of many facets, all of which get their time to shine. This is where the font for the title is established, and headlines first make their way on to the image. It takes a great art director to properly integrate text into a supporting element, particularly when it frames images as lovely as these. And yet it was done, with such understated elegance that today these covers appear restrained, modestly marketing the contents of the stories they hold. But as the decade progresses and makes way for the 60s, a new woman is about to unfold.

The beauty of paging through a book like Vogue: The Covers is the way in which we can be taken in by a single image, completely entranced by a moment in time, and still able to see it within the larger context of both the era and the trajectory of the magazine as a whole. When looking at these images it becomes increasingly apparent what we are talking about if the evolution of the public woman—who is she and how do we relate. Do we want to be like her, defy her, capture her, covet her, or simply stare in quiet awe? Do we giggle at some of her choices or admire her fearlessness? Do we look to the past and see our selves, our ancestors, our kin? Do we look to the present and connect? Do we see the most famous women in the world and just for a split second think, That’s my girl!

Vogue: The Covers is the most fun I’ve had with a fashion photography book in a long time, and that may be because the cover is the most marketable image—the one designed to draw us in, the one that feel simultaneously friendly and approachable while still pushing us to the heights of beauty, a mountain that disappears into the clouds, the summit of which is never to be seen, but for these images a brief shining moment that such glory is within our reach.

Sara Rosen