Elio Sorci was honoured in 1962 with the Paparazzo d’Oro award from the Agenzia Publifoto al Premio Nazionale Fotoreporter. The recognition was surely gratifying, though the award itself had little history, for the term ‘paparazzo’ had only been coined and entered popular usage with the release of Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita in 1960. A character in the film, named Paparazzo, memorably represented the new breed of predatory, celebrity-scoop-chasing photographers who had, through the previous decade, captured and put the media spotlight on the most glamorous and decadent aspects of Roman life. Sorci’s widow, Maria, reminds us that, in 1963, he was named ‘the highest paid photographer in the world’ – a perhaps accurate honour, yet one that underscores the essentially mercenary nature of the profession that Sorci and a band of opportunistic young men had effectively invented a decade earlier. Sorci confirmed this when he explained: ‘…we weren’t tied down by any kind of contract; we sold our photos to the highest bidder’.

Turn the clock back ten years to 1953, and we see the twenty-one-year old Sorci finding his way in the world of press photography. Two singular and contrasting events of that year set the scene for what became an international interest in goings-on in the historic city of Rome as it emerged from the shadows of the war years. It was in 1953 that Audrey Hepburn won an Oscar for her role in Roman Holiday, a light-hearted cat-and-mouse cinematic tale of an incognito visiting princess and a pursuing reporter, played by Gregory Peck. The film captivated audiences with the charm of a modern romance against the picturesque backdrop of the ancient city. The reporter, eventually aware of the princess’s true identity, organises a surreptitious photographic tracking of their time together. In the same year, an altogether darker story slowly started to unravel. In the wake of the discovery, on a beach not so far from the city, of the body of a modest young Roman girl, Wilma Montesi, stories of corruption and immorality emerged, implicating state officials, the police, and an unsavoury milieu of rich, callous hedonists. The Montesi scandal and its protagonists were ruthlessly documented and exposed by a new wave of press photographers, later to be dubbed ‘the paparazzi’.

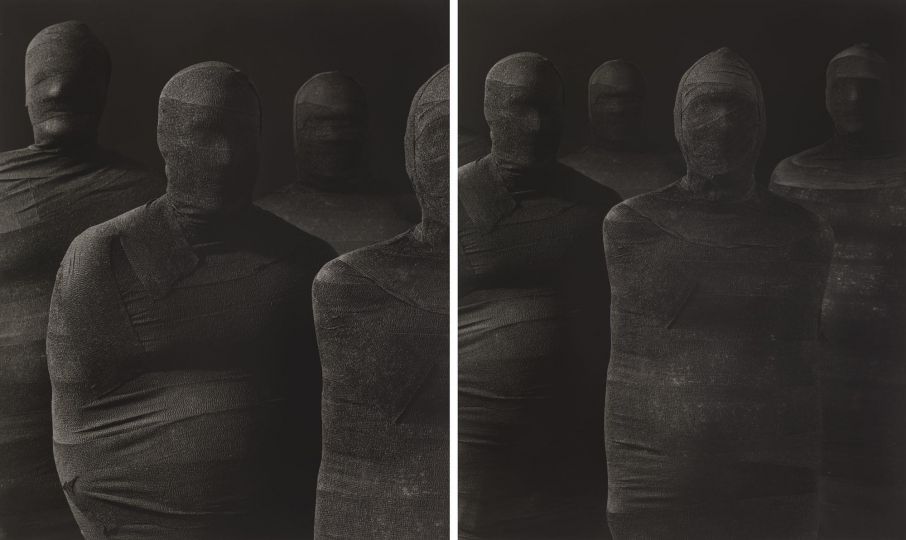

Here, in these two emblematic scenarios, we find so many of the ingredients – both real and contrived, from the most glamorous to the most decadent – that made up the unique flavour of Roman life and provided a generation of fast-thinking photographers with deliciously ambivalent subject matter that filled and fuelled the popular press. Their role was to capture this image cocktail of louche playboys and society figures, camera-fodder stars and starlets, the moths drawn to the flame of what became known as ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’, playing out their dramas in the private villas, nightclubs, Via Veneto cafés, and streets of Rome. The Cinecittà film studios just outside the city were opened in 1937, funded by the fascist government for political ends. Repurposed during the war, their reopening in 1947 gave a fresh boost to the Italian film industry and started to attract international productions, and high-profile stars such as Anita Ekberg, Ava Gardner, and Jayne Mansfield. The stage was set on which the hunters tracking their prey, sometimes entirely surreptitiously, at other times with a degree of playful collusion, would construct for an avid, prurient public the tableaux, blurring the lines between fact and fiction, that constituted the popular perception of ‘la Dolce Vita’.

Elio Sorci, like many of the paparazzi, found his professional path by chance rather than design. Indeed, it might be rightly posited that it was precisely their lack of formal training, their lack of self-consciousness towards the medium, the absence of all those aesthetic and ethical anxieties that can inhibit spontaneity, that cast them so perfectly in the role of ruthless image-hunters. On the essential asset side of the equation, of course, was the mix of charm, speed, canniness, intuition, and tenacity that their work demanded. Here in a few focused phrases we describe the profile that so suited the young Sorci to his profession.

Elio Sorci was a child of the Rome suburbs. Born on 29 January 1932, he was awaiting call-up for his military service when he found his first work in the daily press. Inspired by the example of the attention-grabbing photographs of Ivo Meldolesi, whom Sorci described as ‘the forerunner of all these activities’, he was drawn to the medium and was very soon apprenticed in the photographic department of Il Giornale d’Italia to the already well-established Osvaldo Restaldi, another notable chaser of sensational exclusives, such as his July 1950 image of the body of murdered Sicilian bandit Salvatore Giuliano. Sorci’s fascination was not with the art of photography but with the strategic aspects of the job. He relished the planning and the execution of his targeted image-making. ‘Our activities rotated around what would be published on the newspaper the next day,’ he later explained. ‘What interested me was a journalistic scoop, to get it alone, no matter how much time it took … I considered it my business to get pictures in places where photographers were not allowed … What we did, without knowing it at the time, was begin a new era in photojournalism.’

Within a very few years, in 1955, he founded his own agency and led a dynamic young team in identifying the potential subjects they might pursue to secure newsworthy images whose international distribution in newspapers and picture-led magazines would ensure attractive financial returns. Good information from a network of sources – doormen, waiters, drivers, domestic staff – was an essential starting point. Sorci had no illusions about the predatory nature of his work. ‘A paparazzo,’ he stated, ‘is a young, carefree, happy man who earns his daily bread by putting other people into difficulty and doesn’t mind the risks.’ Some situations demanded patience and near invisibility; others speed and mobility. Sorci waited in the shadows for many hours to catch the moments of intimacy between Liz Taylor and Richard Burton that confirmed their rumoured liaison; his celebrated image of a furious Walter Chiari chasing fellow paparazzo Tazio Secchiaroli, who had just captured the images that would reveal the former’s affair with Ava Gardner, involved a split-second reaction in the tense situation that the photographers had wilfully provoked. And typically, in such circumstances, a hasty escape was effected – most likely on the Lambretta or Vespa scooters that were a part of the stock-in-trade of the profession, not least to get the negatives urgently to the darkrooms that would process the film and produce the prints for rapid distribution and publication. It was essential to be both first on the scene and first on the picture desks.

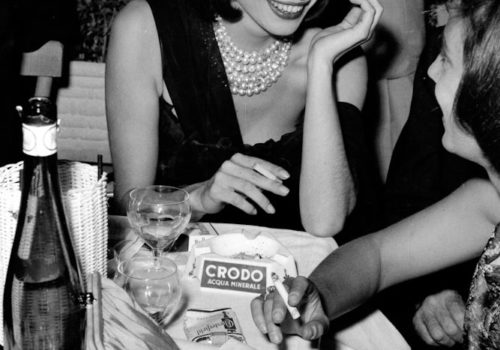

Sorci and his fellow paparazzi developed a new, energised informality in their way of working. While they frequently carried light 35mm cameras at the ready, their first choice, and the most viable equipment for night work, was a mid-format camera with flashgun attached. Despite its bulk, this was a dependable and most effective tool, and the strong flash allowed a small enough aperture to make focusing less critical. The hard, aggressive blast of light gave a raw immediacy to the image. Thus armed, paparazzi could work easily on the move, and this fluidity of point of view and composition, with camera of either format, became characteristic of their technique, as if anticipating the handheld cinematography of the ‘Nouvelle Vague’ directors who challenged the more formal studio conventions of the golden era of Hollywood.

While Sorci and his team were eager to pursue any public figures who might generate a topical, titillating, or controversial story – and his targets included royalty, high society, playboys, dignitaries, politicians, and such singular personalities as the Pope, the Aga Khan, and Jacqueline Kennedy – his principal working milieu was that of the most glamorous film stars, both native Italian and the many foreign stars drawn to Rome. Though Sorci’s independent spirit and appetite for adventure determined his preference to pursue his own, sometimes controversial stories, he was also, as were so many of the paparazzi, invited to make seemingly unstudied on- and off-set portraits to fulfil the promotional needs of the film industry. He became a good friend, for instance, to Claudia Cardinale and Gina Lollobrigida, two of Italy’s highest-profile stars, and photographed Brigitte Bardot during the filming of Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris, and Raquel Welch dancing with Marcello Mastroianni at Cinecittà.

Aware that he had enjoyed the best years of opportunity in his field, and after a serious but manageable health issue, Sorci retired as a full-time paparazzo at the age of forty-three, subsequently closing his agency, leaving Rome with his family, and pursuing other business paths. Through two crucial decades, he had helped invent and promote a new pictorial genre – the mediated imagery of celebrity and glamour associated with the worlds of film, fashion, and the rich and privileged, played out in the spotlight of public curiosity. He depicted this world in indelible images, just as it was, often tinged with vulgarity and essentially superficial, yet at the same time exciting, compelling, and seductive. His legacy is a rich image -bank that bears witness to an exceptional period in social and cultural history. Sorci’s photographs bring vividly to life the personalities who defined that era; they tell of the unique confluence of circumstance that made Rome so vibrant an international playground in the years through which he so effectively captured the spirit of his times.

Philippe Garner