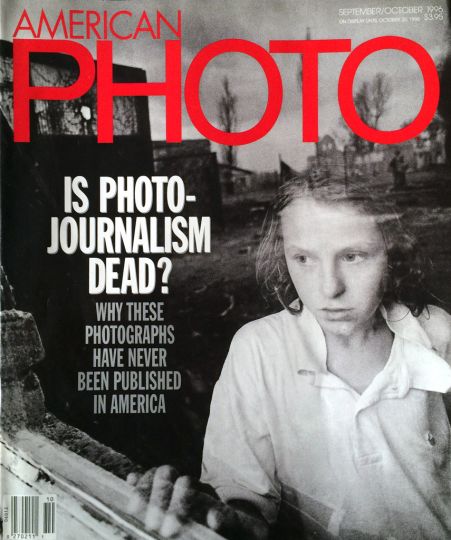

Photojournalism is in transition as a profession and remains an unorthodox career for most. It is certainly not a stable way of life. It has always been a competitive, challenging and dangerous career path, and today it’s never been more dangerous and it’s too often deadly. And it will never return to what it was. In some ways that’s refreshing and presents new opportunities to develop the medium artistically and find a newly relevant and more vibrant place in the expansive media landscape of the digital age.

It’s time to embrace the new platforms of distribution and the frantically evolving forms of disseminating our work more independently today than ever before. One should embrace a more expansive and open minded adoption of multi-platform storytelling, while still producing, books, museum and gallery shows, all held together in concept, form and purpose with firm authorship. For some practitioners like myself, photojournalism can also be a potent force for raising awareness and making change. The growth of advocacy work in the past 5 years has been phenomenal, both in the new opportunities to make a living and to have real impact.

Ultimately as a documentary photojournalist, I want my work and that of my colleagues to be a part of the conversation in geopolitics, social issues, and to be engaged with the world on a deeply serious level. This work can be about stories outside of lives or can give attention to the place you live, even creating stories that emanate out of your own home. This medium can and should be used to tell stories of relevance and universal human conditions, both near and far.

With photojournalists and documentary photographers working across the planet at a quality level and geographic scope never before seen, in many ways today is truly the worldwide golden era of photojournalism. I assume some of you think I’m living in a dream world at this point. Far from it.

Is it harder than ever financially? Absolutely!

Is it harder to break into the profession and find your place? Most definitely.

Has it ever been easy? Never.

The digital revolution has disrupted photojournalism profoundly, and the previous structure of editorial assignments and archive resale has not been replaced by anything one can count on for the future. It’s a time of upheaval, opportunity, elasticity, creative thinking, being open minded and finding platforms that work for you. Basically it’s psychotic. To be in this profession you have to be a bit of a maniac, dedicated and committed to something that is ephemeral. It’s never been more apropos than today.

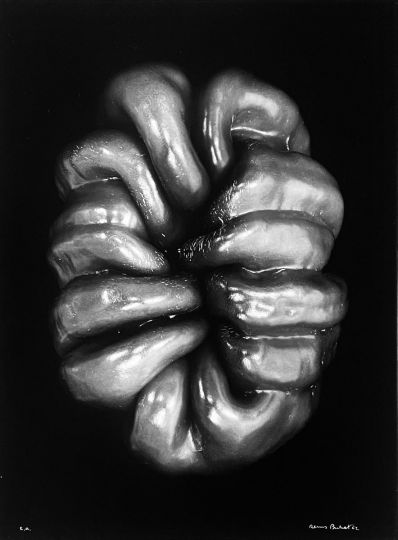

The expansion of the craft with Photoshop and other powerful post production tools has blurred the lines of truth more than ever and allowed for the weakening of certain standards within the profession, opening up old questions about authenticity, truth and the veracity of the profession. Given that photojournalism is after all also journalism, not just photography, we must take this issue seriously. We have big responsibilities and our work and our conduct plays a hugely important role that gives us opportunity to not only witness history, but be a part of it. And I don’t mean that in a vain or pretentious way, it’s just a fact. I’ve experienced it numerous times in intimate, frenetic, frightening and ultimately overwhelming circumstances to get to the story, or the image, or the part of a narrative that is crucial to give the work heft, relevance and at least be the first draft of visual history. Visuals are more important than ever. We must remember that and take great care and reverence in that fact.

Transjournalism, or the use multiple platforms to tell your stories, is the future. In fact it’s already here with various new sites that incorporate stills, motion, audio, text, graphics, etc. For those who want to remain purely still photographers, this is probably not the path for you, but this is the way of the future for visual storytellers who want a place in the new landscape of web and social media distribution.

In terms of funding work, while some publications still provide resources for field work, those opportunities have been greatly reduced. Crowdfunding is a mixed bag in my mind and heart, even though it’s an extraordinary new way to finance your ideas and help to create finished work. New partners like NGOs, Foundations and in some cases corporate/commercial groups are stepping into the breach created by the loss of editorial support. Instagram and social media-we are our own publishers now- is also a potent force for reaching your audience and even bringing in revenue.

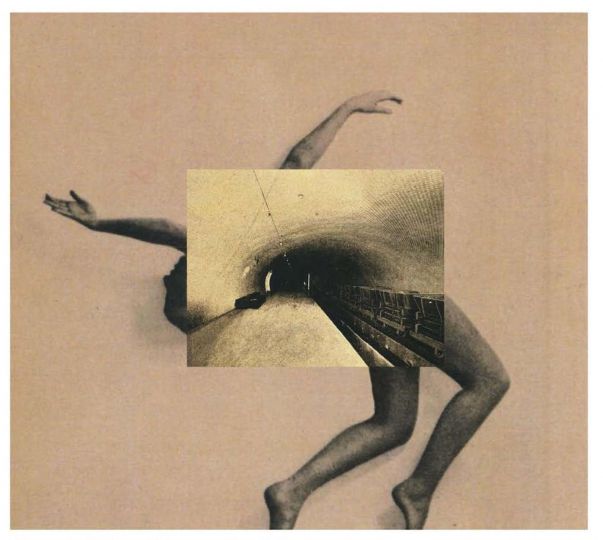

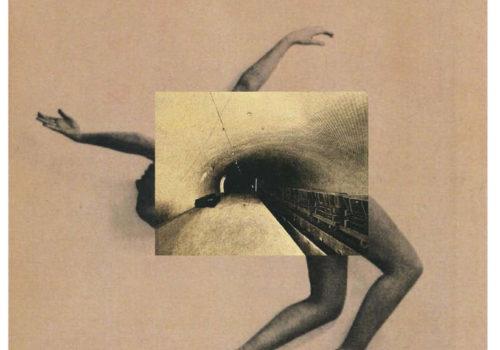

The manufactured rift between art and journalism, which is mainly to support the art world in distancing itself from photojournalism, is to the detriment of the profession. It is dismaying to see how some photojournalists must distance themselves from the craft and profession of photojournalism to be able to succeed in the art world, but alas that is how it goes. It’s always puzzled me how the art world must reject photojournalism that rises to the highest levels of art and aesthetics. There are legions of projects that are also conceptually rigorous and fit comfortably into the precepts of the art world.

The vitality of the craft has never been stronger with the digital tools available, but this profession requires respect to reality and must avoid the urge to enhance reality to make it seem interesting. Reality is powerful enough, and the challenge is to capture it with visual creativity, reflexes, knowledge of your subject and with emotional honesty. Don’t rely on gimmicks to make your work look great

For those who want to do this, I believe one must possess a voracious appetite for knowledge, a maniacal desire to engage with the world, very deep, personal interests that will you to explore issues, places, themes, stories, what have you. And you must have sensitivity, compassion for others, a desire to do good and illuminate. You must read and study and know about the world, especially the subjects you choose to investigate and explore deeply. You must have the reflexes of an athlete in some ways, whether they are fast and responsive, or slow and reflective.

Forty or fifty years ago, if you were a photojournalist publishing in the big picture magazines, you were bringing the world to people and were basically a rare media star. In the 1970’s with the pervasive TV coverage of the Vietnam war, photojournalism took it’s first big hit. Still photographers were not the only visual storytellers bringing stories from “out there” to our homes. By the 1980s there were fewer outlets for long-form storytelling. Then in the 1990s and 2000s the digital revolution changed everything. We all knew it, but many did not anticipate how rapidly things would change.

There are so many opportunities now, coming from all sorts of different places: audio, video, phone cameras – you just need to be flexible and adapt and be able to reinvent yourself. But the onus is on you: you have to have a strong style and vision and an eye for great stories that the media will want. It’s never been easy, it’s never been harder, but at the same time there has never been a more open landscape to work in. And you’ve got to believe in doing it: if you don’t have the stomach for it, then it’s not the right profession for you.

Ed Kashi, Photographer