In 2014, Russian collectors Reikhan and Ulvi Kasimov gave the Multimedia Art Museum, in Moscow, a collection comprising over five hundred press photographs from the archives of the British periodical press of the 1910s. The photographs embody a chronicle of events that took place during one of the most tragic periods in the history of the 20th century — the First World War. Today, an exhibition at the institution presents a limited selection from that collection — about one hundred shots. Nevertheless, those photographs fully reflect the significance of this collection as a priceless source of authentic materials on visual history and of the history of photography.

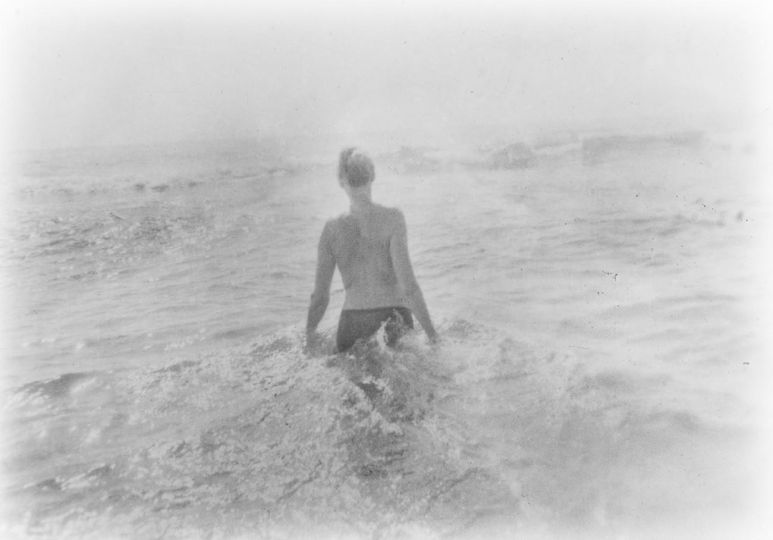

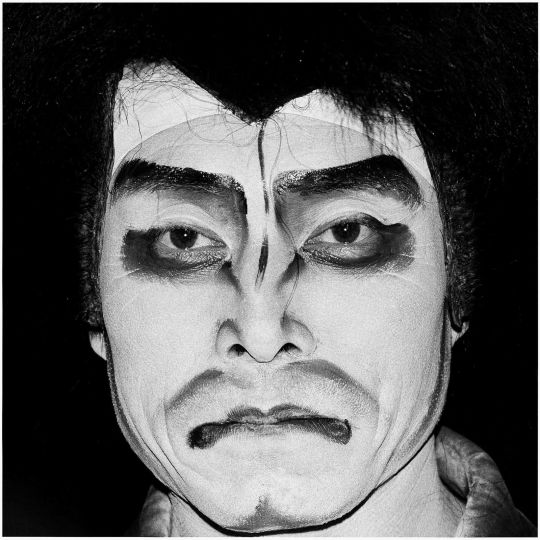

The exhibition relates how swiftly and irrevocably war can burst into peaceful life. Scenes from the daily life of London at the close of the Belle Epoque, high society weddings and social scandals are pushed off the front pages by military chronicles from the frontlines in Europe and Asia Minor, as well as the demonstration of the latest military-technological achievements — tanks and gasmasks. At the same time, the exhibition demonstrates that even during war life goes on. Military reportage and sketches of the daily life of soldiers stand side by side with reports on charity events aimed at collecting resources for the needs of the army, ceremonies awarding heroes and tales of the enormous contribution being made to victory by women and children toiling away in factories and in hospitals.

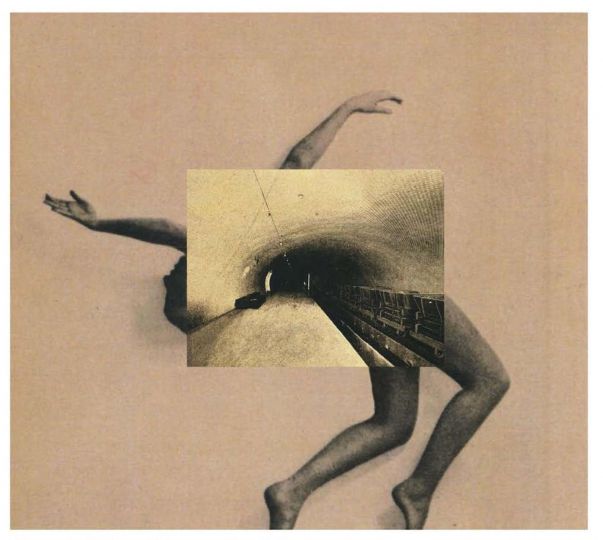

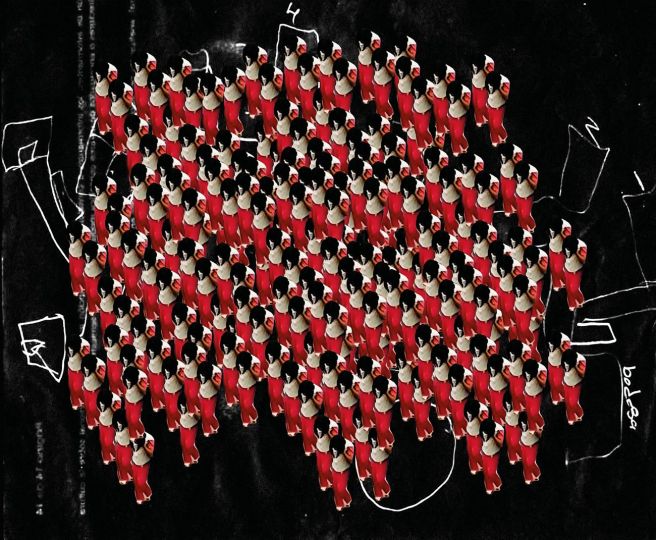

All these images provide eloquent evidence of the tempestuous development of reportage photography during this time of war. Back at the beginning of the 20th century, with the appearance of the technological capability of quickly publishing images in the press with what were fairly high levels of quality for the day, photography altered the visual appearance of the mass media, replacing drawn illustrations and the reproduction of engravings.

The era also made new demands on photographers working in the press and on the editorial teams of periodical printed publications — first and foremost, shots had to be pared down, and photographers had to be able to express the immediacy of events in as accessible a form as possible, getting the visual information over to the reader. In addition, a key role in the process of editorial editing of the shot for print was played by skillful cropping and retouching.

At the same time, in the prevailing circumstances of the period, photographs quickly lost all value following publication, and were often simply thrown away, or at best sent to archives where, sometimes for decades, they were kept in unsuitable conditions — a portion of the works in the collection that was donated were found to be in such a terrible condition that they were literally saved by the MAMM restorers. One of the specific features of press photographs of the beginning of the 20th century was the extensive typed captions on the reverse sides of the photographs, as well as intriguing editorial markings, notes on the cost of reproducing the photograph in the press, the stamps of the news agencies providing the shots and the censor’s approval stamps for the opportunity to be published in publications such as The Daily Sketch, The Daily Mirror and Tatler, among others.

The requirements of photographing for periodical publications were reflected in the style of the photographs themselves. Handling unwieldy equipment, the photographer attempted to balance between the demands of the editorial offices and classical mise en scene traditions derived from painting. Mastery of photographic reportage was born and strengthened before the eyes of readers in the most literal sense — certain shots presented at the exhibition stun with their directness, appearing to have been grasped in a momentary instant from the stormy flow of reality and looking entirely modern even now; in others, an “old school” approach can be sensed, with an inclination towards the staged classicism of the 19th century.

The beginning of the 20th century will always be remembered as one of the most complex and dramatic periods in history. The First World War, the October Revolution in Russia and other events led to the fall of empires that had seemed unshakable, spreading fear, desperation, pain, chaos and death across the planet. Today, a hundred years later, studying the historic evidence of the period, we continually ask ourselves whether these tragedies that took the lives of millions could have been foreseen and prevented.

War and Peace: At the dawn of the European photojournalism in the 1910’s

December 12 to March 18, 2018

Multimedia Art Museum, Moscou

16, rue Ostojenka

Moscou, Russie, 119034