There is something jarring about having Martin Parr select the photographs in Tom Wood 101 Pictures. It is not so much his patronising words (‘he is Irish and let’s face it we all love the Irish’) but the memory of his own photographs in his Signs of the Times (1992): staged scenes showing people in their homes and items of their domestic décor. The accompanying quotations make clear the book’s intent to ridicule ordinary people and expose what the photographer sees as laughable examples of uncultured taste and pretensions.

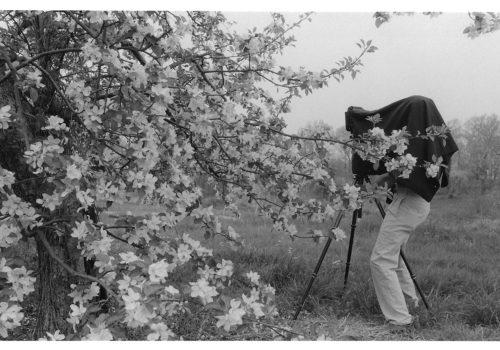

The best thing that can be said about Parr’s work is that he is a documentarist but such a methodology is alien to Wood. He is close to the people he photographs because, while he does not know them personally, he is of them. For a long time, Liverpool was the port of choice for Irish and other emigrants and Wood himself came to Merseyside from Ireland in the late 1970s, staying for quarter of a century. His familiarity with the place and its proletarian heritage provides the essential context for his practice as a photographer of the street. He takes pictures of what interests him, rejecting the idea of working to an agenda: ‘I go out and take the pictures and you figure out what they mean afterward when the project’s finished. The camera is asking questions. You put it all together and you see what it adds up to. Whenever I’ve gone out with something specific in mind, it never works for me.’ His practice generates a style of photography that emerges immanently from his way of working. It becomes what it is.