Written by Juliette Lavie

This article appeared for the first time in spring 2020 in the n ° 4 of the journal Focales of the University of Saint-Etienne http://www.focales.eu

In France after 1945, voices were raised asking that history of photography lessons were integrated into the technical training of photographers in order to “open new horizons” to them, without them having any sucess with official authorities. Only a minority of photographers then have a photographic culture that leads them to know photography’s past. This observation, like the absence of structure, museum and the limited number of works available to access historical knowledge, incited some photographers, for whom the practice is based on a deep historical and technical culture, to take control of their education. Very few, however, assumed this role; and only a few significant initiatives were born in the 1960s in France, the most remarkable of which was developed by Jean-Pierre Sudre (1921-1997). As early as 1957, he offered a technical education in photography which included “knowledge of history and photographic aesthetics. The acquisition of photographic humanities [being] the ferment necessary for the development of taste “. Convinced of the importance of access to masterpieces, Sudre supported his educational commitment with an exhibition program which he established from 1968 to 1972 within the photography department he created at the gallery La Demeure. To pay homage to both a contemporary photographer and a forerunner and gives lectures in which he transmits his unique point of view on photography.

In what context did Sudre exactly conceive these exhibitions mixing current vision and old vision? Is the story he developed the result of the models he has assimilated? How did his peers looked at these manifestations of a new kind, which showcase the models and references circulating among photographers of his generation and favoring creative photography as a collector’s item? Even though he has not taken any course in the history of photography, this photographer, who knows and understands the past as a specialist, sets up at La Demeure a new project, part of the cultural context of the 1960s and 1970s to which Jean-Pierre and Claudine Sudre (1925-2013) and their circle made their contributions.

The culture of photographers (1945-1964)

The publication in 1945 of the History of photography by Raymond Lécuyer and the conferences organized from 1947 at the French Photography Society by the French Photography Confederation for professionals and students of the Technical School of Photography and Cinematography on “the history of [the] profession, the evolution of art, technique, new applications of photography”, constitute the essential of the means available to photographers in France immediately after the war to gain access to historical, aesthetic and technical knowledge. Their culture therefore largely depends on the knowledge of photographers invested in the role of historian, such as Marcel Bovis and Daniel Masclet, who themselves acquired their practical and historical knowledge through contact with their elders: Georges Potonniée, Gabriel Cromer, Raymond Lécuyer, Emmanuel Sougez.

So, when Masclet undertook in 1947 to teach the history of photography to an audience of “amateurs, apprentices and artists”, he offered them a study on the photographic art by taking up references, ideas and images partly fixed in the 1930s in France and the United States. His talk “From Hill to Blumenfeld. A hundred years of Photographic Art ”, accompanied by the exhibition of forty images from his collection, is in fact based on the essay written by Beaumont Newhall for the catalog of the exhibition“ Photography 1839-1937 ”organized in 1937 at MoMA in New York and on the article published in 1942 by Sougez devoted to primitive photographers. The intervention of Masclet allows his audience to learn about the four periods of the history of photography (Before-Primitive-Early-Contemporary Photography) as conceived by Newhall, and of the thesis of Sougez on the primitive mind in photography approached through the study of some photographers from Hill to Atget. This reading, established from the point of view of the photographers, constitutes the model he adopts in this conference, which he takes up in all of those he gave later, the exhibitions he organized and the articles that he published until the mid-1960s in photography journals. His monographic and stylistic approach to creation, inherited from the photographers who borrowed, in the early 1930s, the practices of art critics and historians, led him to transmit the story of the “great masters, their ideas, their styles ”which he justified on the grounds that“ these are our photographic humanities ”. These lessons, because they no doubt escaped no post-war photographer, become the elements of a general photographic culture and found the way of transmitting the history of the medium among French photographers who frequented the Paris photographic club, known as the 30 x 40, where he officiated in the 1950s.

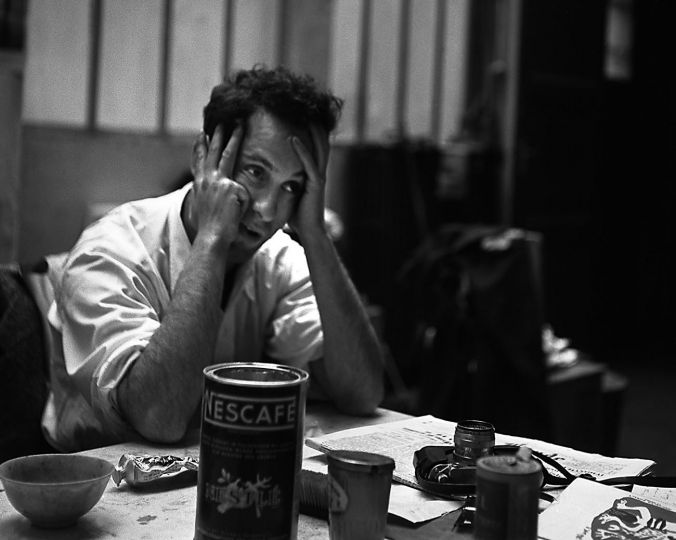

During the decade, Masclet proposed “the history of artist-photographers of all times and from all countries” that he was working on and that he wished to present in the form of a book, the exhibitions on the old and the moderns which he presented, in particular on Edward Weston in 1950 at the Kodak gallery, aroused the vocations of practitioners; that of Denis Brihat, who fell in admiration of Weston’s work, and the vocations of historians, as Jean-Claude Gautrand, who is the most direct heir. Many photographers – Jeanloup Sieff, Jean-Pierre Sudre, Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, Jean Dieuzaide – confirmed, during the posthumous tribute paid to him in 1969, the debt they owed to this photographer who was able to transmit “his passion for Photographic Art” in his “numerous writings, reviews, and essays on photography”.

However, from the 1960s, his words were drowned in a set of historical remarks made by a variety of authors: photographers, collectors, booksellers, historians, curators, who nurtured the culture of photographers. That of Marcel Bovis is one of the most noticed. This photographer wrote articles on the photographic technique which he published in specialized magazines and in which he puts in contact with the former know-how and initiates the youngest in practices fallen into disuse. In addition to these articles, he composed militant writings on the creation of a photography museum in France. That of 1962 is a milestone. Bovis recalls the immobility of “France [which] was preceded on this path and such a museum existed in the United States, the George Eastman House, […] and of course Steichen’s work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Delaying the creation of the Museum of Photography […] is unthinkable, the time has come to act. He proposed to create this museum within the National Library, from the collections of the Cabinet of Prints, to “shelter old works” alongside those which are already there “those of our great elders , Nadar, Baldus, Atget ”, but also the“ Bayard, Blanquart-Evrard, Hill ”whose works he wants, since 1948, for France to preserve and present.

This speech repeated by Bovis and the article by the bookseller and collector André Jammes, published under the title “For an ideal museum of photography” in 1961, provoked the reaction of some photographers including Jean-Pierre Sudre who supported, from 1963, the creation of a photography museum to make known the masterpieces […] of Bayard, Hill and Adamson, Blanquart-Evrard, Stieglitz, Carjat, Rejlander, Emerson, Robinson, Cameron, Atget who are famous photographers from 1840-1910 […]. How could [the student] dream about these masterpieces since there is no place in France to contemplate them? […] Is there a Hippolyte Bayard room at the French Photography Society, a single photograph permanently exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art? There are 54 museums in Paris […], but not one to pay homage to Niépce, Nadar, Carjat.

Initiated like most of his colleagues in the history of photography by Masclet whom he met in 1952, Sudre is however an autodidact whose photographic culture is the fruit of discoveries made at the SFP and readings as evidenced by his library made up of ” varied works – technical, iconographic, historical, aesthetic – and acquisitions, the most significant of which is the purchase of the library and archives of Louis-Philippe Clerc in 1960, including manuscripts on optics, notebooks chemical, laboratory test records. This library, along with its technical documentation, constitutes for Sudre a means of historical and technical knowledge and a tool which he explored and and made available to photographers who come to follow the photography courses which he offered in the Nicole Lab. that he created, in 1958, with his wife Claudine Sudre who printed the pictures of his contemporaries, Sieff and Charbonnier. This scientific and historical culture led him to reformulate his work and to produce, in 1962, a high-quality print, with a single or limited edition, designed to be exhibited and not printed.

Sudre’s knowledge of well known photographers from the 1930s, his interest in old processes, his mastery of the technical and historical bibliography and his frequentation since 1952 of the SFP, but also the friendship that linked him to Roméo Martinez, director of the review Camera, predisposed him to integrate the Study Group of old photography created in 1964 by Jammes within the SFP. Jammes then held the position of librarian and archivist. He was brought by his functions to manage the collection both from the point of view of conservation and of study, and considered the creation of a group of reflections as an essential tool for his actions. It brought together experts: the collectors Christ and Braive, Jean Adhémar of the National Library, Roméo Martinez, the technical historian Maurice Daumas, but also the photographers Marcel Bovis and Jean-Pierre Sudre. In 1965, Jammes, already an essential figure in the world of old photography with his work on Charles Nègre crowned in 1964 with the Nadar Prize which he “showed […] himself at the 30 x 40 club”, promoted the activities of the group in photographic journals.

It announced the objectives which led to his creation, that of bringing together specialists in the history of photography, to study the historical collections of the SFP and to make it known through the publication of works and the organization of ‘exhibitions, with the observation that the history of photography was still in its infancy. The sources are scattered, inaccessible, the specialists few in number […]. Therefore, the sharing of scattered knowledge seemed to many a vital element for the education of all. Knowledge of the past of this art is not a vain archaeological research, for manic collectors or librarians turned towards a dusty past […]. It is, in fact, a true culture that must be brought to the fore of the concerns of all those who are linked to the image in any capacity whatsoever.

Jammes immediately implemented his arrangements through the publication of a work on Bayard produced from calotypes kept at the SFP, which he had printed by the director of Picto, Pierre Gassmann, on the recommendation of Martinez. The work is noticed as is the fundamental role of “Jammes, for whom the history of photography has become second nature, […]. Obviously such an edition (fifty copies) is reserved for museums and archives; it does, however, give a more precise idea about old photographs. This success encouraged the group to gather documentation on 19th century photographers and discuss works and exhibitions: “Paris seen by Atget” then “Nadar” at the National Library and “A century of photography from Niépce to Man Ray” at the museum of decorative arts. Despite the criticisms, noting the disappointment of the photographers vis-à-vis the enlarged reproductions of the original works of Atget presented at the National Library, the exhibitions once again become one of the means of discovering the materiality of 19th century photography, for those who did not ‘had not known the retrospectives of the 1930s, and to acquire knowledge about the history of photography.

However, the project for the creation of a museum where masterpieces of old photography would be presented as Jammes, Sudre and Bovis wanted is reported. And the museum created by Jean and André Fage in Bièvres in 1964, just like the photography department inaugurated at the Réattu Museum in Arles did not change anything as the aspirations carried by Gautrand in 1968 confirmed it:

Where are the humanities of this artistic branch? […] Do we have the equivalent at home of a Museum of Modern Art in New York, a George Eastman House, a School in Saarbrücken or Essen? How can the student, the curious therefore, know the Nadar, the Bayards, the Stieglitz, the Atget who are the history of photography? Where can he discover the Weston, Adams, Moholy-Nagy, Karsh, Steinert, Renger-Patzsch, Cordier, Sudre who are today’s photography?

(…)

The full text is in the French version of L’Oeil de la Photographie