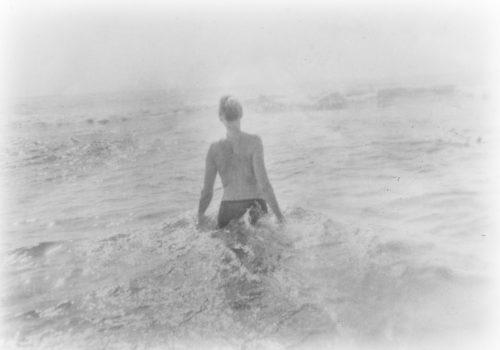

Self sacrificing is the way Cubans have lived for more than forty years: very sensitive and emotional. All one has to do is look at the psycho-architectural layout of their houses: most of the time the front door stands wide open and at the end of the hallway there is a second door, or perhaps a window that allows a quick invisible escape. “So the spirits can come in, and so they can be shooed out,” grandmothers will say. That way the spirits can come and go as they please, in the form of a singing breeze bringing both the melody and coolness that clears the mind. Because heat muddles and harries, heat kills. Long before Feng Shui decoration came into vogue, Cubans had already invented it – without realizing it, of course. The energy of a house’s interior should move from the rear toward the beginning of the room, and the humidity of the walls, or the nearness of the sea, gives relief from the gusts of intense vapor.

How can one capture the warmth of the air? Who dares to hijack the story of a Havana shadow born and lost in that city and then to pursue it, even trap its very evanescence – an evanescence now transformed into quicksilver temptation as it holds a yellow fan representing Oshun, the goddess of sensuality, our own Ashtarte, ruling over a living room in Miami ? Only Robert van der Hilst dares to try — without allowing the glare to burn our eyelids to a crisp. After the American photographer Walker Evans (1903-1975), who took the famous pictures of Havana during the Republic, has come Robert van der Hilst.

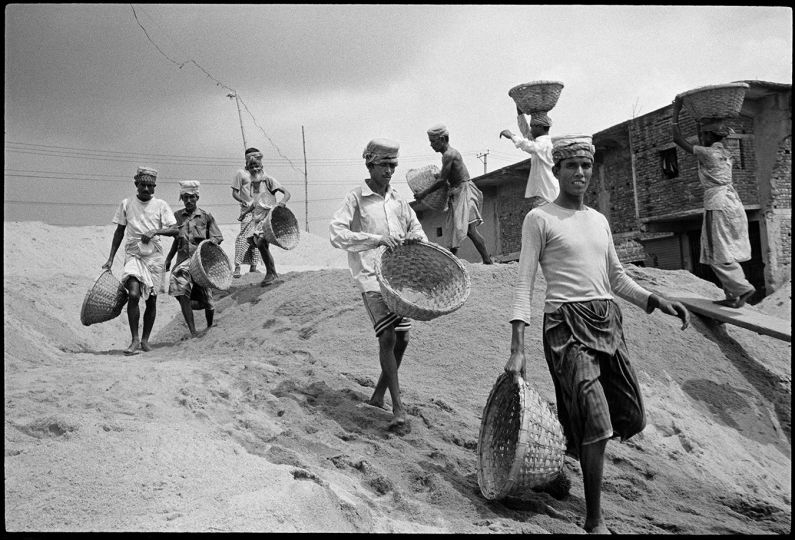

When Robert van der Hilst and I conceived the book titled The Cubans, he spoke to me obsessively about his new series, which he was already calling Cuban Interiors and whose first images he had taken in Baracoa, at the extreme eastern end of the island. What attracted Van der Hilst, the baroque decor ,the exuberant body language , the faded antique elegance, the proud poverty, the spontaneity in the submissiveness of gazes, the infallible iridescence of a plant or a brush stroke on a wall – were precisely what repelled me, because I had lived too close to these things, been a flesh-and-blood part of them. I will never tire of saying that it irks me to see the beauty of poverty in artistic portraits. And of course Cuban poverty (it’s sad to recall) sells well, for few are the consumers able to reflect on the origin of that horrid manipulation whose principal cause and culprit is the Castro dictatorship.

Our book, « Les Cubains », appeared in bookstores and was immediately censored by the Cuban regime. It was the second time Robert van der Hilst’s visa had been denied, although to tell the truth, the first time was in the eighties, when he was accused of being an agent of the CIA, one of the Communists’ common accusation of artists. With that background there was no doubt that he would be a persona non grata, but I was amazed at Van der Hilst’s sudden confusion when confronted to the cultural attache’s diatribe at the Cuban embassy in France when he went to pick up his visa. He was vengefully accused of treason because he had worked with me. According to Robert, the cultural attache, a youngish woman, was dressed in a tailored suit, high heels, very much playing her official role lacking the relaxed attitude and courtesy with which she had treated him on earlier occasions, which had been despite the elegance of her attire – bordering on the vulgarly familiar. I realized that while Robert van der Hilst, unable to grasp what was happening, possessed the tremendous sensitivity to be able to capture the Cuban soul (like the fine photographer he is), like most European and even American artists he missed the terrible degree of subtle monstrousness created by Castroism. The comic and absolutely essential, inevitable detail is that the cultural attache at least tried to look good when she gave him the bad news. And out of the bad news – as always happens ·with censorship – there arose a project that was better more complete, more loved than the first.

At a dinner party in Robert’s house I suggested to him that, if they wouldn’t let him enter Cuba, he should go photograph the Cubans in Miami. One of the dinner guests commented sarcastically that there were no poor Cubans in Miami. All the better, I said to myself. It’s true, to a point, that one will never be able to find poverty in Miami like that into which the island has sunk – with the level of (self-)deception and of ambiguity that is overvalued, identified and signified by unconscious tourists and collaborators with the regime. Never has misery, squalor, poverty been more praised than in Cuba, never has a dictatorship been more shielded, never a criminal like Castro been more “spoiled,” allowed to get away with more.

Van der Hilst went to Mirami and was delighted; his recent work testifies to that. In fact, even as I write these words in New Jersey, he is in the sunshine city for the second time.

I once wrote that Robert van der Hilst has deciphered the hieroglyphics of the Cuban soul, its inimaginary desires. It is a soul that dances as it weeps, and that dreams in eternity’s tempo. And today that soul extends out beyond the diaspora, the flight.

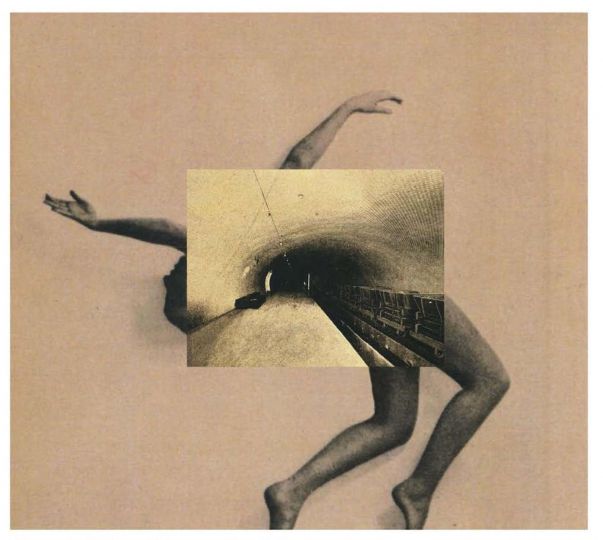

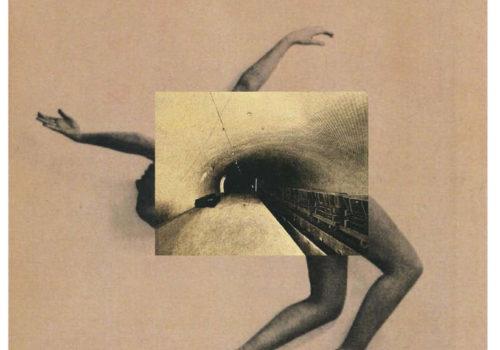

Ever since I first went to Miami and met or saw again my fellow countrymen and women of all kinds, I have realized that it is not Miami that wouldn’t exist without the last forty-three years af Castro rule in Cuba, it’s that Cuba, without Miami, would not be what it is today – a survivor. Without the need to speak of this matter with Van der Hilst, this sens of the quest for a constant imbalance on the shaky ground of a tightrope is very present in his Miami pictures that I’ve seen – because Robert has not yet (it is now August, 2002) been able to stop working on this series, to bring it to a close.

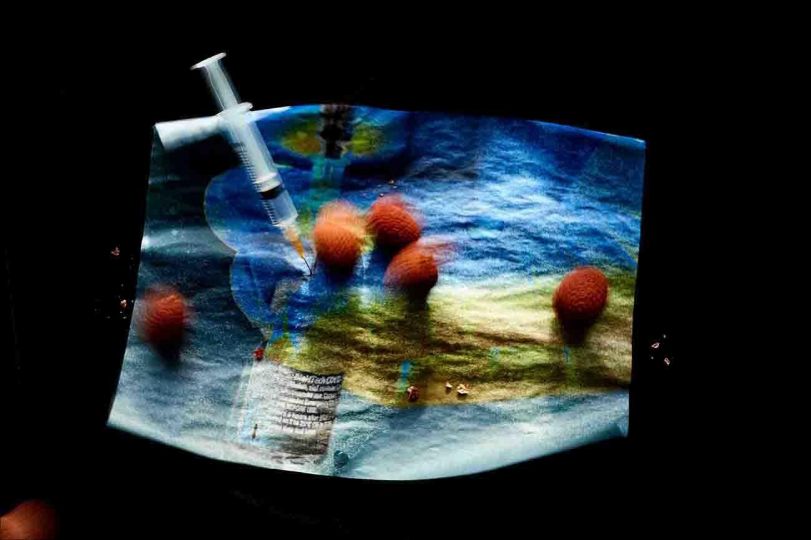

Imbalance and ambiguity are like two fingerprints left on the smoky glass. When one touches mirrors with one’s lips, when one looks into mirrors and sees oneself, the mirrors liquefy, flow in the Heraclitean river of thought and life. The union is sincere in a kiss determined by passion and politics. Families’ wrenching pain of separation has turned paranoia into promiscuity wherever we have gone. The indecent thing about Communist regimes is that everything they touch turns dangerous – becomes ideologies corruption, prohibition, transgression. In a word, crime. And then neither exile nor the dream of liberty can manage to disinfect and heal those forever-open wounds. Cubans escape and take refuge in their religion (which is more a deep-rooted cultural phenomenon than religion itself), as though their lives depended on the last plank of the raft that saved them from the clutches of evil by bringing them across the ocean to Miami. Cuba will continue to be in Cuba that is the implacable logic of geography. But the true Cuban culture – the most authentic culinary, graphic-arts, and literary culture, and even the greatest deeds of valor of its most recent history – wanders the world, and in all honesty we must say that when it settles, it settles mostly in Miami. Settles into an exile that has managed to reconstruct the eternal Cuba of all times-real, and palpable. All this, Van der Hilst has photographed in Miami, the renaissance of a country in exile. .

It should not seem strange that in one of the picture, the iyaloche or madre santera is surrounded by a big-bellied Chinese Buddha, a stylized Indian Buddha, and a Tibetan Buddha. Cubans made a religious rhetoric even out of Marxism. We see the typical black doll dressed as Obbatala, the Virgin of Mercies, a Mexican sombrero hanging in the back wall, a porcelain Vietnamese elephant with its backside toward the door (that way it brings good luck) trinkets like a rainbow memory, and on the wall, the gold-framed photo of another iyaloche, or perhaps the women herself sometimes in her own past; She poses in the center, and is just another figure, a female Buddha, her arms tender as they are held down at each side, delineating her ghostliness. In another picture, the walls are decorated with portraits stuck to the walls. Portraits here and there and everywhere, and again the black doll with her jet-black braids, and the woman is wearing a checked blouse, and she is surprised in a doorway as she respectfully waits for the shutter to snap so that she can come forward and offer coffee.

In the !living room, where one would expect the space to be filled with the most luxurious furniture, the true essence of the woman extravagance – is felt by appearance: the woman herself, both hands clutching the golden robes of Oshun, the Virgen de la Candad de Cobre, the virgin’s gaze vacant under the crown. From her neck emerges not just her head but also the head of the lady on the tapestry in the background, Lezamian chance transforming her into a two-headed deer. A puzzled-looking and life-sized Babbalu Ayé, St. Lazarus, seems to contemplate the sublimization of kitsch. And with his left hand, to be stealthily trying to turn on the TV.

I must confess that in this play of mirrors between interiors in Cuba and Miami, Miami has turned out to be the unexpected one. The sequence of santeras, in which the physical presence of mirrors announces the intention of doubling, as in the plays of Antonin Artaud or a poem by Rimbaud. That ”I” who is Other, the Cuban shadow, the furtive thing in the distance. The captivating captive on each side. And always the figures giving of themselves, whether with their legs spread or thighs camouflaged behind the head of a false lion silence echoes in the drums, and lucid smiles greet one another The gesture of the yellow fan covering teenage breasts competes with the sumptuous elegance of the transvestite head to toe in white, the boy scratching his leg, the kid dressed in blue, oblivious to the situation, responding to the call of the radiant brassiere. Then there’s the irreverence of the peroxide-blond petting her dog, and knick-knacks, and still more pictures. We Cubans need – idolize – the icons of relajo, choteo, which is our own peculiarly Cuban sens of mockery, sport, irreverence. And the queens of grandiose rococo, two elegant mulatto women (as my grandmother would style them), also decked out in glitter and memories. In Miami, people look into your eyes and strip your dreams naked.

And opposite the blinding light of Miami, the opaque light of Cuba. The bluish light of five p.m. perfect for photographers. Grime combined with the green of an ivy plant or two erotic eyes, and a closed curtain. The recurring timeworn things: plastic flowers, calendars from last month, last year, or even before; heroes, saints, dictators, traitors-it’s all the same, they all have the same value on Castro’s farm. Once again I see myself in that little girl with the fixed look of melancholy cutting a cardboard cake varnished in pure meringue. Desolation batters walls and bellies. On a bed, that little girl, wrapped in pink gauze and hopefulness, smiles out at us. God and his sacred heart hold up the soft ceilings about to fall. The windows are hollow nooks. An embarrassed woman covers her face with a white handkerchief while on the floor a newborn takes a nap on a mattress. Before the two very elegant mulatto women in Miami, these second young mulatto women, in Cuba, could be their nieces, who have been melted by desire, hoping to see their baby brother grow up – that child that steps gingerly into the future. Sprawled on a cot, a woman in a flowing white dress smiles, and an American refrigerator as old as Methuselah is her obvious treasure. In Cuba, people hold hands or pose them gracefully, like that old woman who smile gently while the red curtain opens and shows the peaceful, almost divine face of timeworn experience in Cuba, people look at you and strip you naked and make love to you. And the open flame is only the one on the stove in the rundown, deserted- abandoned- kitchen. Do you suppose they’ve all gone off to Miami and forgotten to turn off the gas?

Text by Zoé Valdès