To have been in Berlin in April and May of 1945 was to witness the end of World War II in Europe and the first days of a new epoch in world history. The most famous photograph of those times shows the red flag with star, hammer and sickle being raised over the Reichstag. The event really happened but the picture was a photoshoot. A tremendously dramatic shot and taken at a historic moment but, nevertheless, a staged event taken for the camera.

The photographs taken by Valery Faminsky on the streets of the German capital in April and May are unstaged. He was a young Russian, directed by the army to document in photographs the medical provision for wounded soldiers. Accredited in this way, he was able to move freely around the city. This is what he did and in doing his job he also took the opportunity to take pictures of everyday moments on the streets, not just of Soviet soldiers but German citizens as well.

Returning to Russia in late May with his trove of negatives, Faminsky never showed them. They were discovered by his grandchildren who put them up for sale on the internet. Purchased three years ago and now published, their remarkable authenticity and value is evident, seventy five years after they were taken.

Faminsky’s eye is drawn to what was becoming quotidian in extraordinary times: soldiers relaxing; caring for wounded comrades; commemorating those who have died. He pays equal attention to the Berliners who have emerged from cellars and begun the task of trying to put their lives together again: queuing for food; collecting water in buckets; everyone carrying something that holds precious belongings. Physically they are alive, psychological damage is muted, the debris around them signifying the collapse of a monstrous ideology.

Faminsky’s work holds out the elusive promise of what Paul Levinson calls ‘the immaculate conception of photography’: a pure objectivity preserved over intervals of time. The Russian who roamed the streets of the German capital shows us pieces of lived reality that existed at the time, captured by his non-living apparatus.

We all know, of course, that it is not as simple as this. Transparency in documentary photography cannot be taken for granted; the picture of the flag raising over the Reichstag had smoke, taken from another image, added to create atmosphere and, on the arm of one of the soldiers on the rooftop, a wristwatch (presumably a looted one) was edited out.

Given its provenance, it is extremely improbable that Faminsky’s work was ever doctored but is the absence of something important also form of mediation? A shot of his shows a woman on her own reading a letter and, while it can be seen as poignant, the fact that in late April and May systematic rapes (100,000 could be a conservative estimate) were taking place in Berlin’s ruins is occluded. His camera does not see evidence of the sexual violence and perhaps Faminsky himself was unaware of what the army he belonged to was doing. Referring to pictures of post-surrender Berlin in mind, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay argues in Potential History, that ‘photographs should always be studied in connection to what the shutter sought to keep disconnected from what we are invited to see.’ She calls for a decoding that will reveal what has not been visualised.

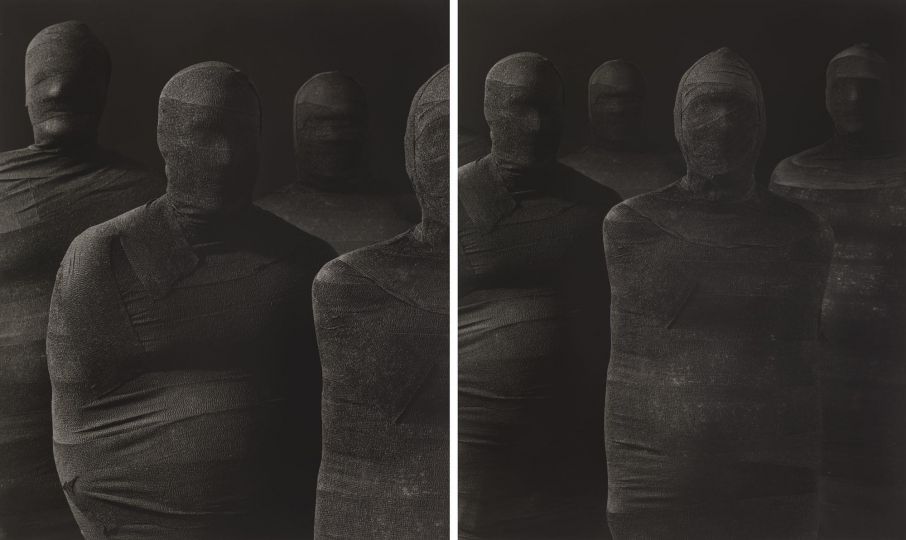

Dieter Keller, serving in the German army, was deployed in the border area between Belarus and Ukraine in 1941-2. Though prohibited from doing so, he took photographs and smuggled the negatives back to Germany. Now published for the first time as Das Auge Des Krieges (‘the eye of war’), Keller’s disturbing pictures contrast strongly with Faminsky’s.

The carefully composed photographs could be stills from a sombre, artistic film like Pawlikowski’s Ida and, like that movie, they evoke unsettling memories of dark times. The Holocaust in Belarus and Ukraine was carried out in group killings, not in death camps, and Keller’s photos of burning farmsteads, children, corpses and body parts in the snow bring this to mind, even if they are not specifically documenting the Shoah.

In other studied photos, of buildings, landscapes and the wintry cold, Keller’s aestheticized style creates a stark, austere beauty that is, to put it mildly, eerie in the light of the historical context. As with responses to Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, ethical questions insist on being asked.

The photographs in these two books, from the same publisher, are as invaluable as they are authentic and they raise contested issues about documentary photography.

Valery Faminsky Berlin Mai 1945 and Dieter Keller’s Das Auge Des Krieges are published by Buchkunst Berlin