Johannesburg is a young city, demographically as much as historically. Founded in 1886 on the promise offered by an enormous underground gold deposit, the average age of a Johannesburg resident today is 25, which is six years more than the average age on the African continent. In a geography defined by its youthfulness, style matters – and has mattered for Johannesburg residents for many decades. In a 1945 letter published in The Bantu World, a daily newspaper aimed at black readers, a man identified only as Mr. J.D.N. of Benoni, a mining town east of Johannesburg, described a new vogue for broad-brimmed hats and narrow trousers (known as tsotsi) worn by young urbanites. These young black men, he told, had a fondness for dance halls and skiving, and answered to the “fancy name bo tsotsi”. Study them, advised Mr. J.D.N. of Benoni, “and you’ll get enough information to write a thesis that will excite many universities into honouring you with degrees”. Generations of writers have followed his advice.

Amongst the many books published about Johannesburg there are volumes discussing the influence of American popular culture on black youth gangs, generically known as “city slickers”, “clevers” and “tsotsis”. There are also tomes exploring the city’s white rock ‘n roll-obsessed “ducktails” and “brazen jazz hounds,” who gathered in 1950s and 60s Hillbrow, the congested inner-city neighbourhood close to where Oliver Kruger produced some of his Golden Youth portraits.

There is even a book on the white musical youth of Springs, a mining town further east from where Mr. J.D.N. lived, who in the 1980s injected a dissident brand of humour into a staid white culture on its last legs. And, of course, countless studies of pantsulas, those purveyors of loose-legged dancing whose uniform of Converse All Star sneakers, Dickies pants and short-brimmed sun hats (or “sporties”) endure as markers of urban streets smarts.

Words, lots of words. But so very few photographs.

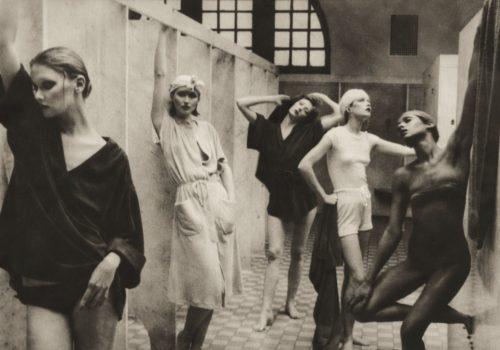

Let me qualify this statement. It is not that photographers past have been uninterested in imaging this cosmopolitan city’s diverse youth cultures. The great mid-century photojournalists Jurgen Schadeberg, Ernest Cole and Peter Magubane all photographed youth at leisure. As did the jazz photographers Basil Breakey and Ian Bruce Huntley. But style, that temporal ideology of youth and redoubt against the impoverishment of daily life, was rarely a subject in and of itself. Rather, it was something noticed in passing: the idea of youth was subsumed by the larger project of documenting the struggle against apartheid.

Apartheid is kaput. But hardship endures, despite the promise of universal suffrage established in 1994. Nearly 500/0 of South African youth aged between 20 and 24 years are unemployed.

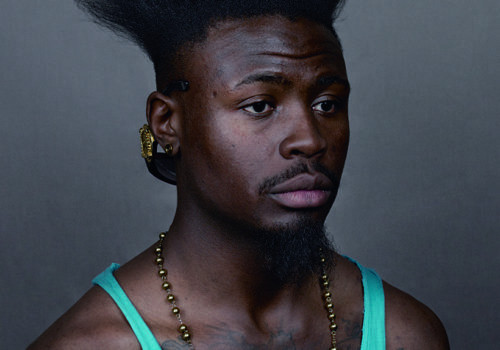

But all these things I mention, facts if you will, are not what drew Oliver Kruger, in 2012, to start photographing the self-possessed young men and women pictured in this book. It was something simpler. It was the “flamboyance” of the young Joburg residents he encountered at STR.CRD, an annual showcase of urban fashion, music and art with a consumer focus, that prompted him to act. And by act I mean, spend the next two years returning to Johannesburg from his home in Cape Town to hook up with, and photograph these descendants of the young style warriors identified by Mr. J.D.N.

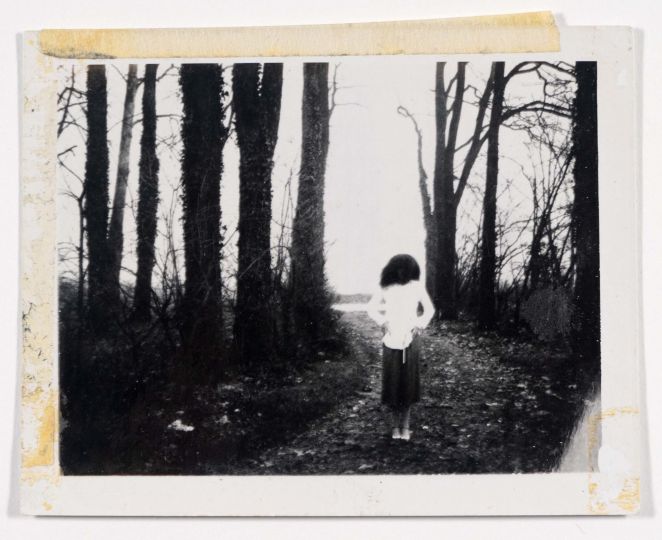

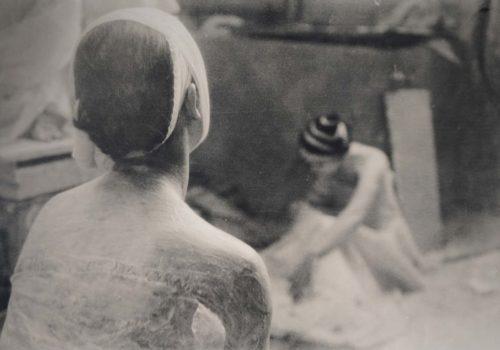

Stripped of context by a neutral backdrop, his photographs momentarily free these young men and women from the meaning of place and circumstance. We see them for who they are, or aspire to be, not for where they come from. While his framing and serial method is dispassionate, Oliver is not a scientist with a camera.

Golden Youth is not a document of any particular Joburg sub-culture, nor is it a study of consumerism. It does not explain the izikhothane, those cloth-burning youths from Soweto who are the latest subject of written enquiry by pedigreed explainers of things. Golden Youth is, quite simply, a portrait study of some Johannesburg youth at a very particular moment in time, the city’s time as much as their personal biographies.

“It is a very thin slice of people seen at a very specific time,” says Oliver. “It is not a broad statement about Joburg.” And yet, he concedes, the idea of Joburg is contained in every portrait. “This particular look and style could come from nowhere else.”

BOOK

Golden Youth

Photography by Oliver Kruger

Text: Sean O’Toole

L’Artiere Edizioni

Size of the book: 24.5 x 30.5 cm

68 pages – Four-colour printing

39 Photographs

Paper Pheonixmotion Xenun

Hardcover Package