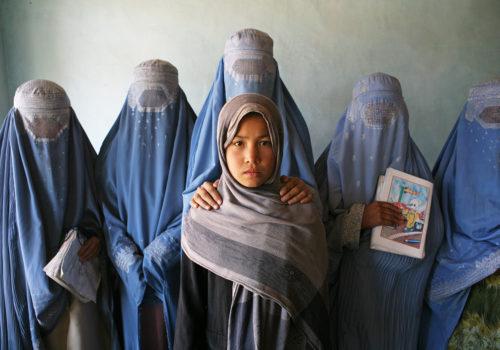

Jean Chung is an award-winning photojournalist from South Korea who believes in surviving power of women in dire situations like war. After living in Afghanistan in 2006 and travelling to Africa from 2008 until now, she has been documenting the lives of women who were affected by war such as pregnant mothers and survivors of sexual violence. Her work gained international recognition such as the Grand Prix of CARE Humanitaire Reportage (2007), the Pierre & Alexandra Boulat Award (2008) at Visa pour l’Image in Perpignan; first place of 4th Days Japan Photojournalism Awards and WHO’s Stop Tuberculosis Partnership Award (2008), and 6th and 7th Days Japan Photojournalism Awards (2010 and 2011). She is also in an Ambassador Program for Canon U.K. (2017)

She is currently a contract photographer for Getty Images based in Seoul, South Korea, and is working for international media notably The New York Times, Bloomberg, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Getty Images, Stern, Der Spiegel, M -Le magazine du Monde, Time.com, among others. She hopes to tell her visual story and deliver the voices to the world about the women’s side of the history of armed conflict.

Website: https://www.jeanchung.net

Publication links:

https://www.amazon.com -> In the search window, enter “AFGHANISTAN – When Afghans Took a Breath of Freedom: A photojournalist’s journey in the country 2006-2007”

Patricia Lanza: What was your motivation to pursue the subject of Women in Conflict areas?

Jean Chung: I lived in New York for eight years and moved to Missouri to attend graduate school. It was a month after I moved to Missouri when 9/11 attacks happened in 2001. It was such a shock for me and made me wonder what drove people to such madness. I began my search for the reason for the conflict between the Western world and the Islamic world, and wanted to find the root of the problem. During the Spring Break in 2002, I decided to go to Israel/Palestinian Territories to look for the answers instead of sitting in front of the computer reading news about suicide bombings in Israel. I realized there had been lots of misinformation thus creating misunderstanding about Palestine and the Islamic world and how they viewed the U.S. and the Western World.

I also realized there were many things in common between Palestinians and Koreans. Korea was a weak kingdom that was later colonized by Japan. We had a temporary government and independence movement, but they were painted as terrorist’ acts. The Western world did not recognize the temporary government as the legitimate representative of Korea. That’s when I thought I should know more about the conflict region.

The motif of having an interest in women’s rights in the conflict area stemmed from my stay in Afghanistan in 2007. I learned from a gynecologist at the Ministry of Health that Afghanistan had the second-highest maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the world. Since I was a woman, I thought this topic should have been reported by a woman journalist. I flew to an Afghan province called Badakshan – which had the highest MMR in the country – and documented the death of an Afghan mother who gave birth to a son. Someone told me that my project to document maternal mortality was “impossible.” But I was able to do a photo reportage on the issue and realized it was God’s calling.

Patricia Lanza: In War and conflict discuss the weaponization of sexual abuse and purpose?

Jean Chung: Most wars are waged by men, and there’s usually sexual violence against women. I think the concept of “Rape as Weapon of War” had already existed when the Mongol troops invaded central Asia in the 13th century. The troops invaded the villages, raped women, and killed men. The history repeated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the 21st century. Militias from different rebel factions invaded villages, looted and raped. Gender-based Sexual Violence (GBSV) was so cruel, it 1) terrorized the population, 2) humiliated the men and 3) made women infertile so that it could lead to the genocide of a tribe in the long run.

In the eastern part of the Congo, the armed conflict between Hutu rebels from Rwanda and Tutsi rebels from the Congo was intensified. Women in the villages either got killed or sexually assaulted. Many of them suffered from “traumatic fistula” that causes the leaking of urine and/or feces as a result of the severe rape and attacks.

Patricia Lanza: Rape is rarely documented and prosecuted in conflict zones , discuss the aftermath affect on its victims?

Jean Chung: Gender-based Sexual Violence has always been a part of war e.g. The World War II, the Vietnam War, and the inter-tribal wars in Africa. In the Congo, rebels would hide in the bush, come out in the night, carry out the offensives, then vanish to the bush. It is hard to distinguish the perpetrators, furthermore, to prosecute them.

Survivors of GBSV suffer greatly both physically and psychologically. Many of them suffer from “traumatic fistula” as mentioned before, and are also mentally humiliated and devastated. Many of them are from poor villages, and uneducated. They have a hard time having a normal life as a woman as well as a human being. Some die of severe physical and mental damage.

Thankfully, many NGOs and counselors helped these survivors in the Congo. They comforted them and taught them job skills such as crafts and sewing. Some of them also learned how to manage the micro economy and sold small goods back in the villages.

Patricia Lanza: How did these women and girls feel about telling their stories?

Jean Chung: Before I start my interview, I usually tell them that I want to tell their stories to the world. Of course, some women do not want to share their stories with me or ask for money for the interview. I only interview those who agree. They usually don’t tell me how they feel after the interviews, but many of them have said that they were impressed by me visiting them constantly with compassion. Many of them said “God bless you” to me regardless of their religion. Those women have gone through some of the most horrific experiences in their lives, and yet they had a heart to bless someone.

Patricia Lanza: Discuss the challenges you experienced in pursuing this topic?

Jean Chung: However, not all reporting goes rosy and smoothly. When I follow them and take pictures, there are usually young men and children surrounding me and the women and shouting at us. One time I was photographing two former Boko Haram abductees in an IDP camp, the children and young men surrounded the hut and kept yelling something. They also surrounded the car that my fixer and I were inside and beat it.

Also, there had been many incidences where local security personnel demanded bribes at checkpoints and even detained me and the NGO workers who accompanied me in the Congo.

Patricia Lanza: What do hope will come out of your reporting?

Jean Chung: The basic purposes of my photo reporting are to document the history from a woman’s point of view and to raise awareness. However, after years of reporting, I realized what the survivors needed was cash assistance.

At first, I donated money to hospitals and NGOs personally; but later I teamed up with a South Korean NGO to donate bigger sums of money to local NGOs, especially the ones that were lesser known to the international community. Also, I looked for organizations that were comprised of local women who were helping survivors. I always took pictures of me handing out donations to them and received the receipts to show the South Korean donors.

Women in South Korea also suffered from colonization and war throughout our modern history, and I was happy to volunteer as a bridge between Korean women and other women in the conflict zones to build solidarity.

Patricia Lanza: And what are you working on now?

Jean Chung: After the outbreak of Covid-19, I didn’t travel outside of Korea for more than three years. My father is terminally ill, so I decided to focus on the issues in South Korea. I am working on a personal project about birth rates in South Korea.