For many there is a belief that man holds dominion over the natural world; that it exists for us to do as we wish and bend to our will. That man is may somehow be inherently superior to the water, the earth, the land, the sky—and to all other animals that share these spaces with you and I. Perhaps this is most evident in the idea of hunting for sport, to take down with a gun the creatures that could otherwise tear us to shreds. Some hold to this as a right granted by a Biblical passage from Genesis, which states, “…and God said unto them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and replenish the earth and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.”

As Bill Kouwenhoven notes in his introduction to David Chancellor’s Hunters (Schilt Publishing), “Rather than using their dominion properly, but husbanding the animals and the land, the First Family [Adam and Eve] set a pattern of destructive domination and overexploitation that has continued to the present day. The clashes between Cain and Abel are prima facie evidence of the unintended consequences of pastorialists following their animals around and farmers with their settled and demarcated properties…. Yet it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that this balance began to tip radically in a new and irrevocably dangerous direction.”

It is on the other side of that tipping point that we find ourselves today. Foreign imperialists took hold of Africa and carved up the land of Original Man for pleasure and profit, without concern. Amongst their countless violations of life and liberty include establishing the practice of East African hunting safaris that have gone on for over a century. Today, South Africa has the largest hunting industry, while several other counties follow closely, with the creation of big game parks that are designed to service the bloodsplattered dreams of foreign hunters.

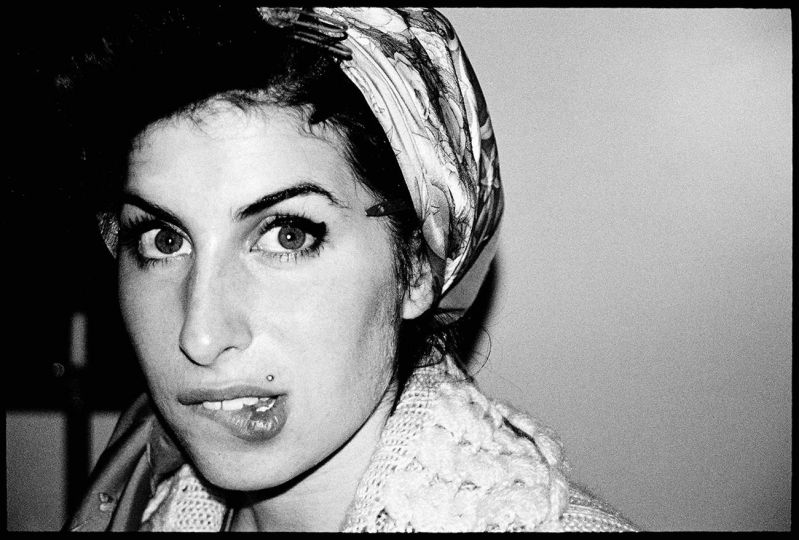

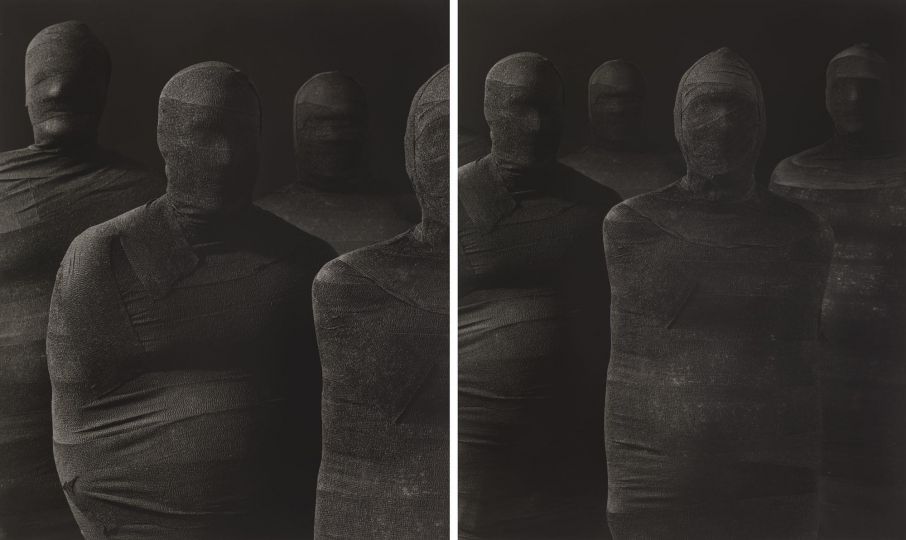

In Hunters, photographer David Chancellor explores the people inhabiting industry today, documenting the landscapes, the hunters, and their kill in a series of portraits likely to either disturb or to thrill, depending on your perspective about the sanctify of all life and the responsibility (or irresponsibility) of mankind as guardian of those who share this planet with us.

As Kouwenhoven notes, Chancellor takes a nuanced approach to the Game, maintaining an ambiguity brought on by the post-colonial economics of the continent, which help to fuel the mythologies of the hunt and of Africa in and of itself. By including George Orwell’s classic essay, “Shooting an Elephant” at the end of the book, along wit a series of images that show the transformation of the corpse into nothing but bones at the hands of a group of Africans in a series of photographs, Chancellor’s images raise questions which, in and of themselves, may reflect the pre-existing biases of the viewer while simultaneously reinforcing them. I know this to be true for me: I am all the more horrified and disturbed by my feeling of powerlessness when I look upon these majestic creatures mowed down for the thrill of the kill and the pleasure of sport. It is in this same way I imagine one who enjoys their dominion would be excited by the pride and bloodlust exhibited here.

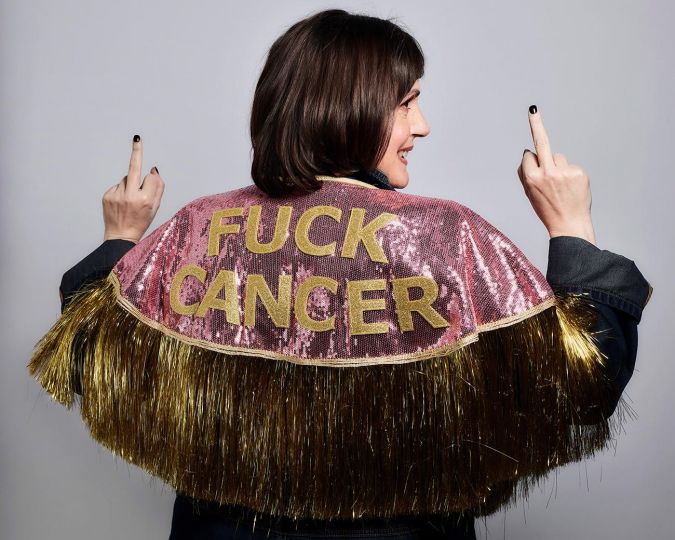

Counterbalancing the images of the wild made dead are Martin Usborne’s photographs of the domesticated creatures that man has allowed to flourish and live. The Silence of Dogs in Cars (Kehrer Verlag) is astounding document in that what we see in these photographs is our very own reflection, belying the assumptions about the inner emotional life of animals. The phrase “Abnthropomorphism” is a slight of hand, a means to invalidate the projection of humanity onto non-human beings—yet is is just what it sets out to erase; it is the very assumption in and of itself that emotions belong to human beings and to no other creatures; a doubtful, if not harmful and arrogant supposition at best.

Usborne’s photographs take us deep inside ourselves by allowing us to consider that in every creature there exist the possibility of a mutual understanding that goes far beyond words. The emotionality of each image, the sheer visceral force of recognition, the acknowledgement of a deep inner life in each of these portraits is a haunting reminder of the soul that exists, for me, in all living beings.

Dogs have earned our highest honor: the title of “man’s best friend” is nothing short of an elevation beyond all other non-human beings. It is not just in their relation to us, but in our relation to them that this connection takes hold, a bond that dates back countless millennia and manifests as a union of souls. We see this, or rather feel this, when we gaze upon Usborne’s subjects, some who gaze upon us in return, others whose glance is directed at that which we cannot know. But still it is felt, a kind of longing, a bond that is broken by virtue of the dog being left behind in this enclosed vehicle.

As Usborne notes in Susan McHugh’s introduction, “These images are about separation. On the one hand, they are about the separation between humans and other animals; the dog in the car could just as well be a bird in a cage or a tiger in a zoon or a fish in a tank. The car represents the brutal way that we often control and silence the animals in our lives. On the other hand, the images are about a deeper and subtler separation, between us and ourselves, I suppose. We all have parts of ourselves that we keep silent, locked away inside; feelings trapped like the dog in the car.”

Perhaps then it is not the animal—domesticated or wild—that is the Other, but we, so deeply disconnected from our own humanity and the earth itself that we try over and over again, by re-enacting this same failed paradigm of control and death. How we treat others, animals and humans alike, is a reflection of our own feelings of self. When we look upon Chancellors and Usborne’s photographer we are given the opportunity to consider our prejudices, biases, assumptions, and the meanings we create around that which Nature has given us to share of this Earth.

Miss Rosen