A feral child is one which has lived isolated from human contact, often from a very young age. As a result the child grows up with little or no experience of human care, behaviour or language. Some were cruelly confined or abandoned by their own parents, rejected perhaps because of their intellectual or physical impairment, or the parent’s belief that this was the case. In other instances the loss of both parents was the cause. Others ran away after experiencing abuse. Yet more ended up in the wild and were ‘adopted’ by animals as a result of a wide variety of circumstances – getting lost, being taken by wild animals, etc.

Documented cases of feral children are geographically spread over four continents, and vary in age from babies taken by wild animals up to eight year olds. Of course, these cases are only known of because the child survived. It is not difficult to think that there are probably untold cases where the outcome was less favourable.

It is documented that, in most cases where rescued children were very young before becoming feral they do not recover or develop the ability to speak or adjust to normal life and in some cases do not even move as normal human beings, preferring to continue for a long time to walk on all fours, climb trees, eat raw flesh, etc.. There are only a few instances where they have completely adjusted to a normal life – speaking, reading, writing, and communicating. There are several instances where the rescued child became the subject of intensive scientific research – to attempt to determine the origin of speech and language.

As a mother of two young boys I was appalled and intrigued in turn when I first learned about feral children. My initial reaction was to think how parents could either neglect or lose their child. My maternal instinct goes into overdrive when I consider these young people experiencing their lives alone or in the company of wild animals. Then I consider and admire the fortitude they must have shown to survive such isolation and extreme circumstances. In any of the circumstances that I have read about, it completely overwhelms the boundaries of my comprehension.

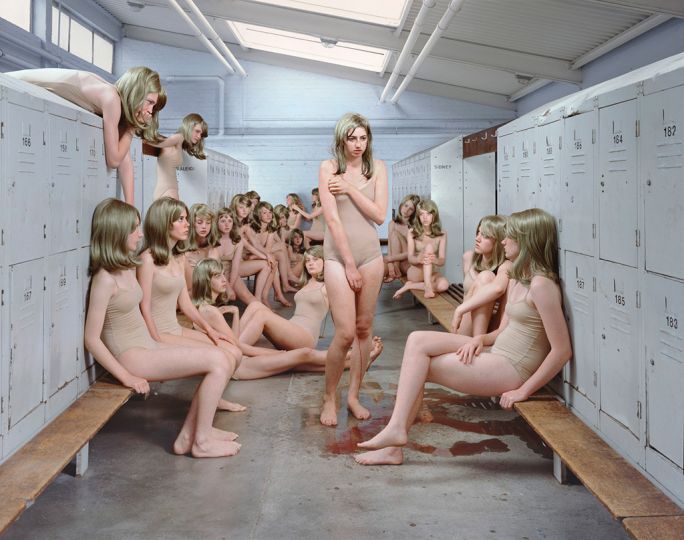

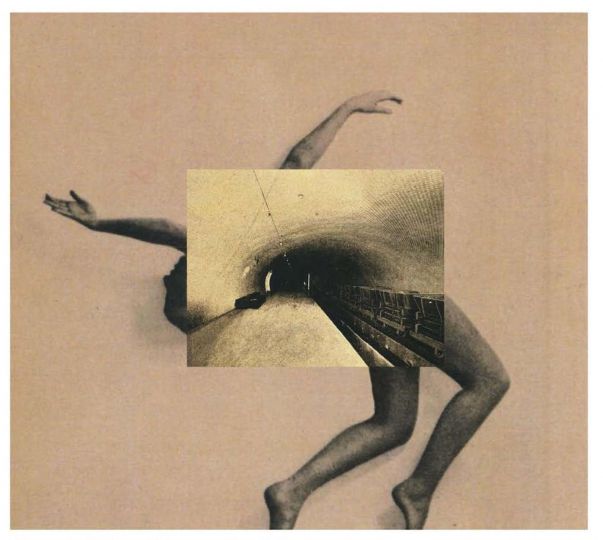

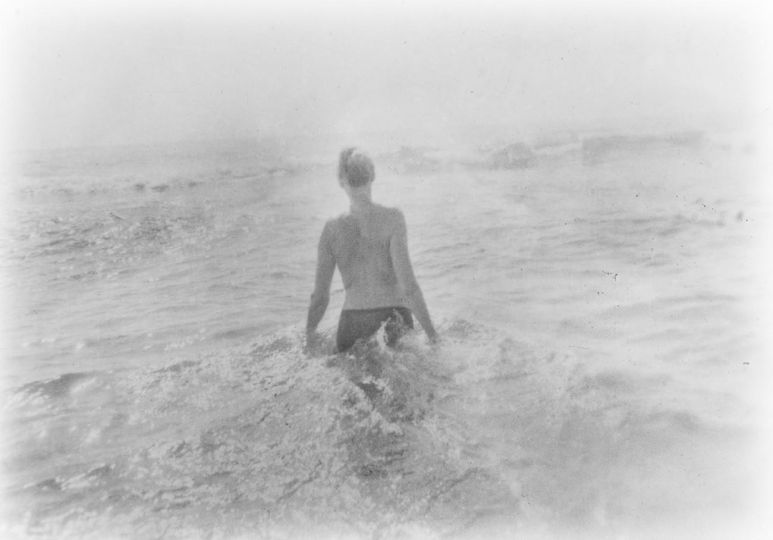

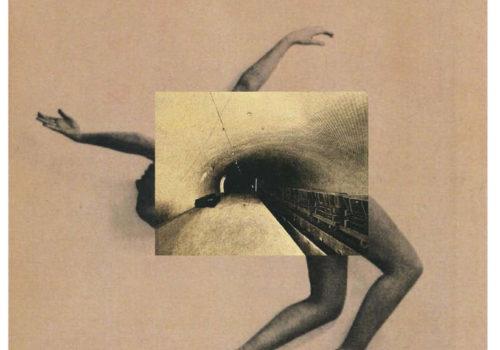

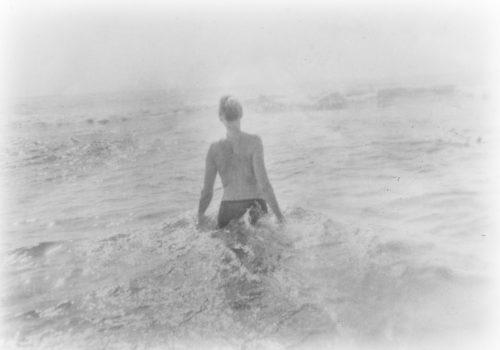

However, I have risen to the challenge of trying to capture my thoughts photographically about the isolation under which these youngsters found themselves, wondering at the same time if those living in the companionship of wild animals were perhaps better off than those whose young lives were spent with no companionship at all.

I chose 15 cases to portray, these range from a girl who as a toddler was confined by her parents to a potty chair for ten years to that of a baby boy who was stolen by a leopardess and found three years later in the company of her and her latest cubs. My idea was not to replicate the exact scenes, but to interpret and duplicate the feelings and actions of each feral child living their experience. Some spent most of their time indoors, even in close proximity to or inside human habitation. Yet others spent the duration of their feral life outside, exposed to the elements, depending on their own ability and that of their wild companions for shelter and food and water, not to mention constantly having to avoid danger and health problems.

Life is complex, for some more than others, even when we are considering a normal human life. Its complexity varies from one part of the globe to the other. In considering feral children, who are fully human, at least at the start of their lives, how can we not look at my images and question and wonder about the tenacious survival instincts of these 15 human beings.