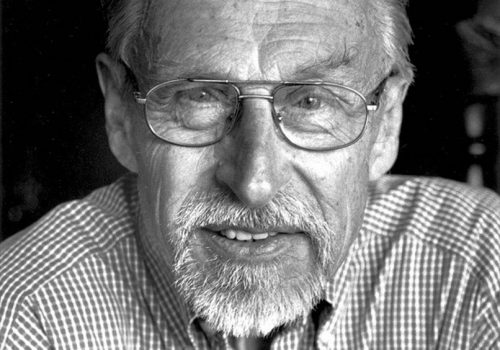

From January 18 to March 3, 2018, Galerie Argentic in Paris presents a selection of about fifty photographs by Jean-Claude Gautrand, French photography’s privileged witness. This selection covers over 60 years of work and brings together his most beautiful series, including Métalopolis, Le Galet, L’Assassinat de Baltard, La Mine, the Forteresses du dérisoire, and Le Jardin de mon père. Today, the Eye of Photography devotes a special edition to this supremely talented and little known photographer.

Jean-Claude Gautrand photographs the way a sculptor cuts stone or shapes metal, and he structures his compositions like an architect. Rigorous lines, majestic volumes, light and shadow mastered by a skilled hand, all create a space that constitutes his trademark style, influenced by Subjective Photography. However, Gautrand’s oeuvre goes beyond virtuosity and technical prowess. Time, an invisible component of photographic research, innervates each of his series. Time is not considered from an airy, metaphysical or intellectual perspective, but rather as a foundational reality, a thickness, indispensable matter, a cornerstone, and, finally, as the principal subject of his work.

His oeuvre is traversed by an underground temporal flux, which the different series clearly foreground or discreetly suggest. Time disappears in order to resurface where it is the least expected, starting with the famous Assassinat de Baltard [Assassination of Baltard] or the views of Bercy, to devastated villages, to the ravaged lands in Boues rouges [Crimson Mud], to broken trees. In his war trilogy, time becomes memory. The three series that make up this chapter take stock of the vestiges of a disaster: the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp, the ruins of the French village Oradour-sur-Glane, and Atlantic Wall bunkers in Forteresses du dérisoire [Forteresses of the Derisory]. As we look at these photographs, the theme of Vanitas comes to mind.

“The living do know that they will die, but the dead know nothing, and they have no reward because their memory has been forgotten.” Oradour fills us with dismay conveyed by the photographer’s personal vision and, paradoxically, because of the lack of dramatization; there are only ruins and shadows under the sun: a tragedy had taken place. Three rows of barbed wire in a snow-covered field are enough to evoke the suffering endured by the prisoners at Natzweiler-Struthof. The bunkers in the Forteresses du dérisoire, relics of German fortifications on the Atlantic coast, captured in the process of decay, create a completely different impression. These concrete structures, very symbolically devoid of foundations, disintegrate in every imaginable way: fractured by telluric forces; poised on a cliff ledge whose base has eroded; gradually overgrown and buried by vegetation and soil; subsumed by nature; subsiding into the sand; or toppled from the hilltop where they were built, are now lapped by the waves. A whole grammar of obliteration emerges from these images. Gautrand never yields to the temptation of a superfluous effect that would over-signify the tragic past of his model. Rather, he photographs them directly, like sculptures, showing the material of the walls, the play of light and shadow on the edges and surfaces. He foregrounds structures, cubes, very graphic cracks, and subtle nuances of gray. And yet… His personal genius, as in the photographs of Oradour-sur-Glane, consists in conjuring, from a visual record, the tragedy marked by these structures like by cenotaphs, and in making the silence and the ghosts palpable, all the while remaining true to life.

And here is Paris! The Paris of the Baudelairian flâneur, the Paris of Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project, a city already faded, subdued, a ghost chased by Eugène Atget in his most beautiful photographs — in fact, the real Paris, the city of native Parisians, appears in all its mystery and fleeting beauty in the images made over the years by Gautrand. While the destruction of Baltard,[1] followed by that of Bercy,[2] have literally mutilated the city, depriving it of neighborhoods most firmly anchored in the imagination of the Parisian walker, here and there one can find a fleeting presence of the city’s former charm, this “dark atmosphere” that the photographer excels at bringing to light. No tourist, no visitor could ever capture the genius loci with so much insight. We are overcome by an acute sense of melancholy before these images of wet pavestones or snow-covered streets that seem to sum up all the myths that the city has engendered over time. In the end, this is precisely this kind of Baudelairian melancholy that characterizes Gautrand’s oeuvre.

While his unsettling and haunted vision and his sense of tragedy find in the agony of a myth their ideal subject, these qualities are no less present in the intimate series Le Jardin de mon père [My Father’s Garden]. There is nothing monumental about this series: a few square yards of derelict nature, leaves and fruit in all stages of decomposition, occasional tools worn with use and the passage of time. The mystery of absence inhabits places and things, whose durability confronts the fragility of living beings and of the organic world. “No fruit ripens in my garden now,”[3] wrote Baudelaire… The photographic object cuts close to the question of death. This is the very meaning of “That-has-been”[4] in Roland Barthes who, thinking he was writing a book about photography, in fact was thinking through the issue of absence.

Anne Biroleau-Lemagny

Anne Biroleau-Lemagny is General Curator at the Départment des Estampes et de la Photographie at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. She lives and works in Paris.

Jean-Claude Gautrand, Itinéraire d’un photographe

January 18 to March 3, 2018

Galerie Argentic

43 Rue Daubenton

75005 Paris

France

[1] Baltard refers to Baltard Pavillons, another name for Les Halles de Paris, designed by the architect Victor Baltard, and demolished in 1971. — Translator’s note.

[2] Bercy Village, a neighborhood in the 12th Arrondissement in Paris, was once an independent commune, and a vibrant community of merchants and wine vendors. By the 1960s, the area had been practically abandoned. In the early 2000s, the neighborhood had undergone restoration and modernization, and has been converted into a strip mall. — Translator’s note.

[3] Charles Baudelaire, “The Enemy,” in Fleurs du Mal, trans. Richard Howard (Boston: David R. Godine, 1983), p. 20. — Translator’s note.

[4] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), p. 77. — Translator’s note.