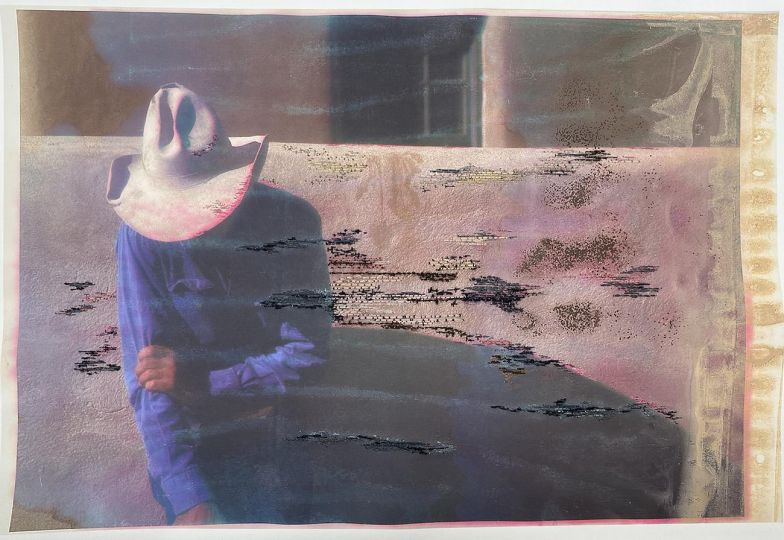

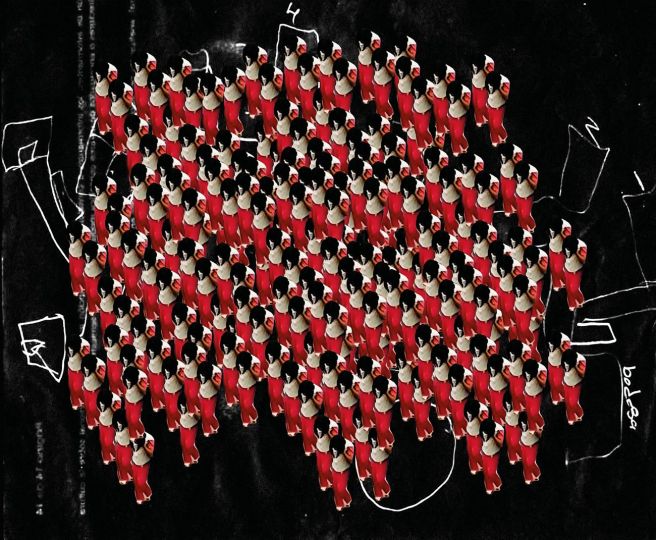

Photographer Danielle Kwaaitaal (b. 1964 in Bussum near Amsterdam) graduated successively from the Bijenveld Fashion Academy in Amsterdam (1987) and from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy Amsterdam (1991). During her studies she discovered the possibilities of digital editing when she was allowed to work with the very expensive Paintbox during an internship. This was a powerful graphics workstation developed in 1981 for editing television video and graphics, with an initial price tag of around €600,000 (in today’s terms). Needless to say, Photoshop (which was only first commercialised about 1990) was not really a competitor at the time. Kwaaitaal was a pioneer, and her graduation project Bodyscapes was awarded and purchased by the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

Sensuality is the second constant in Danielle Kwaaitaal’s work, or should we say sensuality and the femininity? In Bodyscapes eg, she created landscapes by assembling images of her own skin. Soon she adds the third constant, water: in Bubbling from 1994, she submerges bodies under water, and photographs details with the air bubbles.

It also reflects a search for a renewal in the visual language, because to Kwaaitaal reality in itself is unsatisfactory, reality is boring, there is nothing lofty about it.

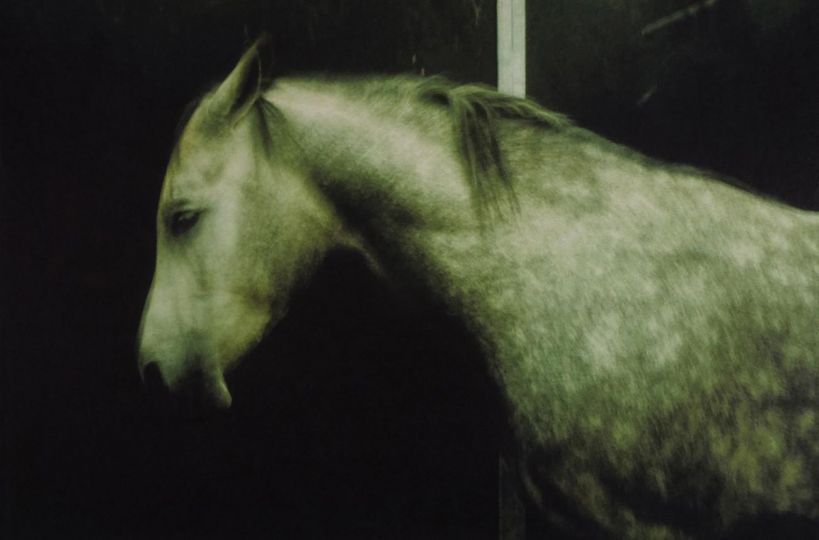

From then on, these elements keep reappearing in various combinations and with new accents. Airheads (1998) are underwater portraits of people from the Amsterdam club scene, followed by FLO (2004), Wild Waters (2004), and Whispering Waters (2009) and Fallen Angels (2010). In these last two series, it seems as if the photographer is taking a more contemplative stand, and is again innovative. She precedes a long line of contemporary photographers to depict the motionless, graceful and dynamic female body under water

In Brussels, the Michèle Schoonjans gallery presents an exhibition entitled Still Water with three recent series by Danielle Kwaaitaal: Florilegium (2017-2018), Ultraviolet (2020) and Zephyr (2021). After a few years of research, she reconnects with her original approach as already described above

In Florilegium, cut flowers are synonymous with sensuality. Florilegium is the Latin translation of the Greek word Anthologion, which means… Anthology. In Dutch, the original Greek word is translated literally around 1750 as “Selected Flowers”, in the sense of “Selected Beauty”.

The subject matter in this series, cut flowers reflect that another Dutch tradition, namely the still lifes of the Dutch Golden Age. In the 16th century, a war raged in the Netherlands, fuelled by political, religious and economic differences. A large part of the population from the south sought protection in the north, a situation that is very similar to what is happening in Syria or the Ukraine. Successive military victories, colonial expansion, economic growth, philosophy based on individual responsibility and commitment, and the political stability of the new state ensured a period of prosperity and well-being for the bourgeoisie in the Northern Netherlands. The upper class also wants to give charisma to their prosperity by buying art , but under the Reformation, they no longer revert to the Roman catholic imagery. Instead, genre scenes and still lifes were preferred. Precisely the latter were highly appreciated: they emphasise beauty but also bear witness to the ephemeral nature of life.

Florilegium follows this tradition, only she doesn’t choose to shoot the series in a traditional studio on a tabletop, but submerges the flowers in water tanks built for her. She adds colour to the water, which then creates density (and depth of field) and a specific atmosphere. The flowers are weighted down, and when taking the picture she has to act quickly, as the bubbles on the flowers provide their own touch, which Kwaaitaal describes as ‘gifts’.

The two following series mark a break in Kwaaitaal’s work, as she replaces nature with objects. The reference to the compositions of Giorgio Morandi 1890-1964 is obvious, and to the outsider there is little difference between the two series. In Ultraviolet (2020), she uses mainly ‘recent’ glass objects such as perfume bottles, which she completely anonymises, and in Zephyr (2021) she prefers historic pottery and glass objects she collects.

The artist herself says about her work in these series that the difficulty lies in searching and finding the right composition. It is precision work, which is of course also influenced by the choice of materials. Historical glassware will give different effects.

For the three series, the photographer works with a medium format camera. The size of the tanks determines the image, just as the space of the studio makes an image. In post processing, she inverts light and colour so that it seems as if the subject is radiating light.

Kwaaitaal does not see herself as a photographer but as an artist with a camera. In these series, she finds the balance between digital manipulation and photographic realism, and achieves a mastery of the shots. She explains her approach & method very openly, as if she is aware that her originality lies in the mastery of the analogue recording and the precision of the digital processing – lies in the specific knowledge based on a long experience. A weak imitation is possible, copying isn’t.

John Devos

PUBLICATION

Danielle Kwaaitaal FLORILEGIUM

With essays by Wieteke van Zeil and Arjan Peters; design by Tim Bisschop

Price 39,90€ l 192 pages

Size 33 x 24 cm

ISBN 978 90 8967 326 8

The deluxe edition, limited to 100 copies in a linen-covered hardcover & cassette, contains an original signed print of the Florilegium series.

Price: 199€.

Publisher Hoogland & Van Klaveren

EXHIBITION

DANIELLE KWAAITAAL – STILL WATER

13 March – 30 April 2022

Galerie Michèle Schoonjans – MS Gallery Rivoli #Gallery 25,

Waterloosesteenweg 690 Chaussée de Waterloo,

1180 Brussels (Bascule),

+32 478 71 62 96

www.micheleschoonjansgallery.be

Open Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 11 am to 6 pm and by appointment.