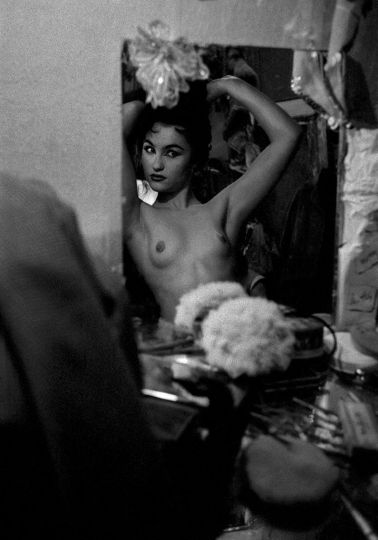

Frank Horvat was born in Italy in 1928 and was one of the first artists to apply the 35mm lm camera and reportage techniques to fashion art photography starting in the late 1950s. He created a new and more realistic style that revolutionized the development of fashion-based photography in England, France, and the United States. He stylistically combined realism and artifice, movement, and inventive locations, which won him immediate success as a French fashion photographer. Horvat initially worked for Magnum photos, but since he “posed” his subjects he left for Realities and Black Star. He moved to Paris three years later and currently divides his time between the city and the south of France.

Frank Horvat’s photographs have appeared in leading European and American magazines including Life, Elle, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Glamour and Jardin des Modes from 1951-61. Horvat’s work with French fashion photography has been exhibited around the world and can be found in the permanent collections of numerous prestigious museums including Bibliothèque Nationale, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Kunst-bibliothek, Museum of Modern Art, the George Eastman House, and numerous other collections. In his over seventy years of photography, Horvat has experimented with numerous subjects and techniques and continues to explore the possibilities the medium has to offer.

Before settling in Paris in 1955 at the age of 27, you lived in a variety of locations such as London and Milan while also traveling to such places as Pakistan and India. How do you think these experiences shaped your artistic outlook in general and interest in photography specifically?

I wouldn’t say that the places shaped my outlook: but that my outlook shaped the way I photographed those places.

You have mentioned meeting Henri Cartier-Bresson in the early 1950s at a young age and the influence he would have in directing you and your subsequent work. Looking back, what do you think you took most from meeting him and where do you think you deviate most from his philosophy on photography?

For Cartier-Bresson, it was not enough to just record a fraction of reality that to him seemed worthy of note. But he had to match it to a grid, which he called “composition” and which did not only fit the Golden Rule, or some aesthetics taught at Art School, but to be a concentrate of everything he had felt, understood and interiorized since he first came into being. The ‘miracle’ is the unforeseeable – but perfect – coincidence of that grid with the reality seen through the viewfinder. Or rather: the immediate recognition, by the photographer, of that coincidence. And above all: his determination to seize it by a pursuit that may be unconscious or clumsy, but that will not stop at any compromise. It is by this coincidence that photography can transcend the subject. And that it can also transcend it’s own craft and become not so much the equal of poetry, or of painting or of music, but a new form of art, a hybrid of the real and the imaginary, of the objective and the subjective, of what is observed and what is constructed, not necessarily according to the rules of traditional art, but not less powerfully and with as much significance. I don’t believe I deviated from that. I am just myself and not him, lived in a different time and used different instruments.

Your innovative fashion photography in the late 1950s is thought to have launched your career although your work outside of the genre and also in subsequent years does not always involve it. What have you learned from shooting fashion photography and how has the genre related to other subjects you have photographed?

I would say that my fashion photography is closely related to my other photography. Without what came from my other photography, it wouldn’t have been interesting or successful.

You have said that a good photo cannot be taken again and that they are “small miracles.” How do you think this viewpoint makes you differ from other fashion photographers?

The photographers who are not seeking what I call “a little miracle” are not part of my club.

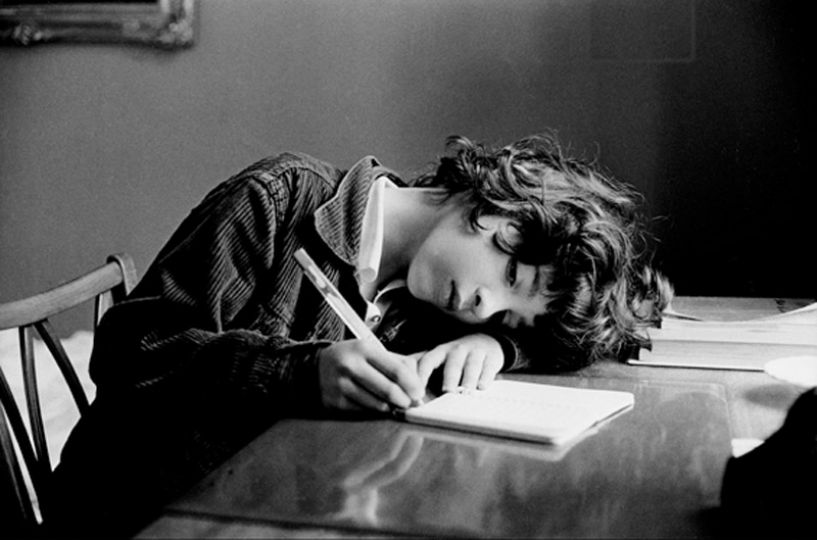

You have interesting views on portrait photography and have used a character’s feelings in a Dostoevsky narrative to summarize this: “The only reason why photographic portraits are seldom recognizable are because people are seldom themselves.” What is the essence of a portrait to you and what do you believe would contribute to making a successful portrait of an individual?

To me, a good portrait shows what I recognize, at a given moment, as “the essence” of that person. Of course, I may be unsuccessful, or mistaken. But I am definitely not interested in what that person wishes to show as his (or her) essence.

You have said that later in your life your perspective has shifted from that of being focused on the subject to being more focused on what you have to say through an image you capture. In what sense does the object in a photograph become a conduit for the expressive powers of the photographer?

Being less mobile, I have just become more self-centered. This happens to older people. It has its positive and its negative aspects.

Throughout your long career you have shot several different subjects and used many techniques as well as types of cameras and technology. Looking back at your oeuvre and in order to unify your images you have used the concept of The House with Fifteen Keys. Could you briefly explain this concept and how you arrived at it?

Why keys? I’m at an age when you look back and try to make sense of it all. I’ve been lucky enough to take photographs for almost 70 years, in a period when the world has changed more than in any comparable time span. To live in six different countries and to travel to several more. To think, speak and write in four languages. To photograph many subjects, from different viewpoints and with different techniques. To have other interests besides photography, such as writing and olive growing. My eclecticism had its drawbacks. Some questioned my sincerity. Some found that my photos were hard to recognize, “as if they were by 15 different authors”.

This is why I’ve sifted through my work (or what’s been preserved of it), searching for a common denominator. I didn’t find one – but 15. Running (more or less) through all those years. I call them keys.

You have always embraced new technology in your photography whether it is experimenting with Photoshop in the late 1990s or with digital photography. How did new innovations in the field of photography affect your work and your outlook on photography?

Every new instrument allows to show different subjects and opens new horizons.

Having been at the forefront of fashion photography during the 20th century, what do you think of the industry today and where do you see it going given the context of the 21st century and new technology?

Fashion photography has become something else than what it was to me. Most of what I see now is pretty girls and excellent craftsmanship – but few miracles

How do you think your iPad application that includes extensive commentary about individual images will influence your legacy? What are the potentials for using this technology?

It is an important part of my legacy. The potentials of this technology are immense. I wish good luck to those who will explore them.

What is left to say and do in your world concerning photography?

You will know when you see it – if you get to see it.

This interview is part of a series conducted by Holden Luntz Gallery, based in Palm Beach, Florida.

Interviewer : Kyle Harris

Holden Luntz Gallery

332 Worth Ave

Palm Beach, FL 33480

USA