The Free-Handed Photographer

Who is René Groebli? He is a blind spot. Perhaps he is the proverbial blind spot, the “Missing Link” in the history of modern Swiss photography.

Who is René Groebli? This is René Groebli. The publication on hand summarises his essence. These are early works, non-published portraits like that of Brassaï, lost dummies, jump start images that in Switzerland remained undiscovered, milestones in photographic history. These pictures at their time were not only on track, they were themselves laying this track. Only the most visionary in Germany and America understood the new signs and formulated with Groebli’s artistic statements an alphabet for the future of the medium.

The first to notice him was the American photographer and curator Edward Steichen, the visionary Steichen who had towards the end of the 1940s established at the New York Museum of Modern Art the first photography department world-wide. For the museum’s collection he acquired Groebli’s image poem Das Auge der Liebe (The Eye of Love). The Swiss also formed part of the monumental MoMA exhibition The Family of Man (1955), the attempt at an all-encompassing portrait of humanity that until today travels around the world. Steichen’s successor John Szarkowski in turn integrated Groebli in his exhibition The Photographer’s Eye (1964) and afforded him a special place in the publication of the same name. In Germany Otto Steinert, the important post-war photographer and professor at the Werkkunstschule Saarbrücken, member of the vanguard group fotoform, recognised Groebli’s potential. He showed his movement studies in the exhibitions subjektive fotografie (1951/1954). The dancers in the Zurich Tresterclub (1947) embodied for Steinert the visionary possibilities of the medium, the State of the Art of progressive photography.

Characteristic for this artist: he is an artist in motion. Movement is his inner nature. Therefore he never implemented the development of his art in a linear fashion, the single image as a static icon. On the contrary, he thinks the medium centrifugally, outwards from its centre. And this centre means movement, is dynamics. It is the archetype of creativity.

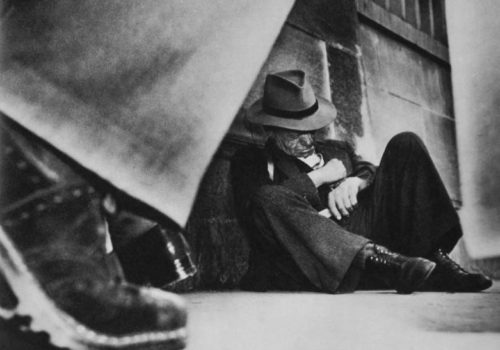

Who is the young René Groebli? It would be simplistic to label him as the counter-thrust to what in Switzerland of his time dominated the academic convictions and actions of the photographers. Groebli subjected himself at the Zurich Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts) to this regime of Hans Finsler and his factual school of the dead-fixed “precision aesthetics” only for half a year. Even before that he had drawn attention with his choice of unusual town views, improper cropping and unusual perspectives, his view a swoop from far above. And this with unphotographic subjects: Abandoned brass instruments on the tarmac, an orphaned horse-and-carriage on a rain-wet street. In the Landdienst he was interested in the wooden structure of a barn, the man under the roof a jocular aperçu. 1946 and now in Hans Finsler’s class he points his camera to hustling passers-by on the Zurich main bridge (Quaibrücke), blurred and thus unaesthetic, a shocking behaviour, a breach of the rules of the prevalent photographic dogmas.

Still in the same year he photographed what he later will refine in many variations: The tension of time caught in space. The drive towards the dynamic that spells modernism. And in consequence: Following his stint at the School of Arts he decided on an apprenticeship as a documentary cameraman. Groebli, forging ahead without being aware of it, riding free-hand on his bicycle, photographs the street before him. He does not photograph what is, but what will be. Groebli aims to understand the essence of movement in the sense of a cineaste and the enticing energy found in what is new.

The image taken across the handlebar of a bicycle presages something vital. Above all it points to Groebli’s early masterstroke with which he a mere three years later, in 1949, will proclaim and confirm his talent: A self-published picture essay, Magie der Schiene or Rail Magic, as he self-confidently names it for the English market. René Groebli is a mere 22 years old.

1949, in search of a free theme, he visits Paris. Here he gets to meet Brassaï as well as Robert Frank and several artists with whom he will maintain friendships over many years. That a rich crop of first-class portraits are created along the way he hardly seems to notice. Many of these have remained unpublished until now, like the picture of Robert Frank or that of Charles Chaplin. The series showing his long-time friend Brassaï in his private rooms shows the compositional talent of Groebli and his delight in the composition. That the plethora of books in the library of the photographer seems to be in a state of chaotic dissolution, that the stage setting draws the observer into the depths of the room he must have liked very much.

In Paris he starts a project that addresses itself to railway tracks, train stations, commuter trains. Finally he photographs on the trip from Paris to Basel in the driver‘s cabin of an express steam locomotive, on the tender and even on the running-boards.

With the motive of the steam engine Groebli intuitively chooses the decisive metaphor of the time. It is the metaphor of great artists when they talk of the dawning of a new age, a new dawn and change: William Turner’s rain in the picture Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) or Claude Monet’s Gare St. Lazare (1877). The locomotive is the general motive of technology buffs and futurists; but photographers of their time with a sure instinct like Stieglitz also employ it, he calls his picture of a steaming locomotive rolling towards the observer The Hand of Man (1902). Groebli, however, does not limit himself to single photographs, he will create a portfolio with cinematic leanings, without compromise, full of contrasts, Rail Magic, a gigantic overstraining of contemporary taste. But artists like Max Bill and Gottfried Honegger recognise the novelty, they support him. It is not long before the series begins to influence young photo artists not only in Switzerland. Groebli’s pictorial language, his narrative aspects and the serial quality become exemplary. For he still is not present, that other photo-cineaste Robert Frank who is so akin to Groebli.

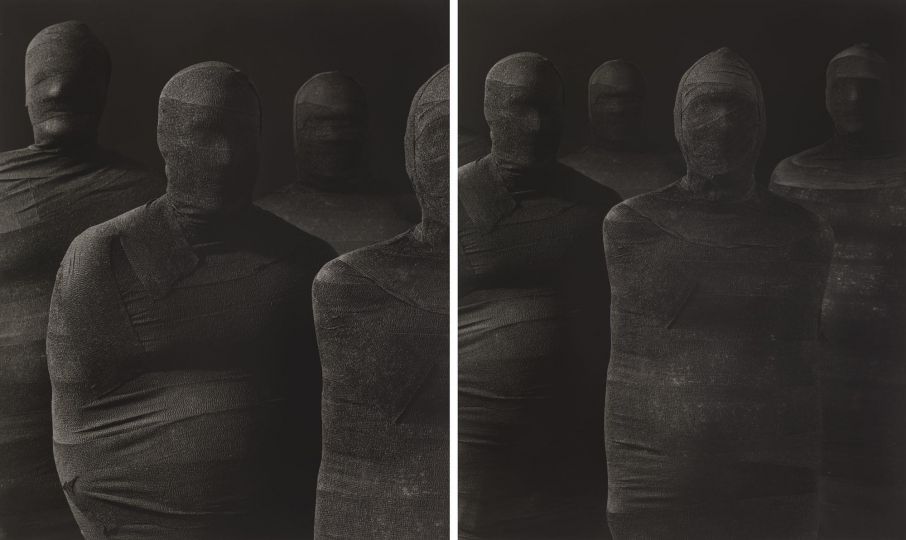

Similarly affected is the second portfolio work of this kind. Groebli calls it Das Auge der Liebe or L’oeil de l’amour (The Eye of Love, 1952). He designs it together with Werner Zryd, a graphic artist he met through Robert Frank. The love poem to his young wife Rita recounts a trip to France in the mood and the cinematic language of French poetic realism. The work is spectacularly misunderstood in Switzerland and seen as an homage to free love. For no one realises that here a photographer has chosen freedom: The independence to think the medium forward, to charge a tale with energy, to give it dynamism in form and content – as if the Leica was a movie camera.

But Groebli remains imperturbable. For two years he worked as a successful war reporter for the British agency Black Star, he is on the move carrying a bulletproof vest and photographs corpses. Of course this, too, he masters, his photographs are printed in the important media like Life or Picture Post. Groebli’s instinct for high drama is great and he can, if he so chooses, even relegate the aesthete in him to the second rank.

Yet the desire to be able to create unencumbered cannot be supressed, luckily. He again dares to tackle a lyrical poetic subject. Like a master of the Italian neorealism cinema he photographs in 1953 in post-war London a young Jamaican immigrant, Beryl Chen. Through her person the enthusiastic photographer tells an intimate, fleeting story of hope and longing. It is the same longing for beauty and future that links the two, the artist and his model. The book design, this time created by Werner Zryd on his own, remains unpublished for more than sixty years. Only published in 2015 it makes clear: René Groebli is the missing link in the Swiss photographic history of the second half of the 20th century. He merges the romanticism in photography with the visions of the technician, the modernist. His decisive publications were made years before those of Robert Frank. In their power they are his equal, as to their impact the works of Groebli are yet to be discovered. Be prepared for surprises.

Danieel Muscionico, July 2015

BOOK

Early works by René Groebli

Sturm & Drang publishers 2015

Available 21. Sept. 2015

first edition 2015

160 pages,

30 cm x 29 cm

hardcover

german/english

ISBN 978-3-906822-00-6