The review is superb. Its name is Pinault Collection and it is published twice a year. In the lastest issue: this wonderful subject on the Bourse du Commerce in Paris directed by Anne de Mondenard.

The photographers who depicted Paris had ambitious goals and varied perspectives: guided by their personal interests or fulfilling a specific assignment, some focused on the city as a central motif while others presented it as a backdrop or décor for other activities. They captured its architecture, its dwellings, its businesses, and, of course, its inhabitants. The earliest images of the Bourse de Commerce date from the Second Empire (1852–70); the most recent were taken after the Second World War. During that century, the building, the street that surround it, and, more broadly, the urban fabric within which it is nestled, changed profoundly. It is important to keep this context in mind in order to fully appreciate the different takes of the many photographers, both celebrated and anonymous, from Charles Marville (1813–1879) to Roger Henrard (1900–1975), including Eugène Atget (1857– 1927), Henri Godefroy (1837–1913), and Pierre Emonts (or P. Emonds, 1831–after 1912).

Let’s begin with Charles Marville’s well-known depictions of Paris and its transformations, created between 1865 and 1868. When Marville captured the Halle au Blé, he was on assignment for the city’s Service of Planning. Marville did not focus on the circular Halle au Blé, designed by Nicolas Le Camus de Mézières. Marville was tasked with capturing the six streets that converge on the rue de Viarmes, which circles around the building. The systematic way in which Marville proceeded is noteworthy, and today, this commission is seen as an important beacon of modernity. In his series, the Halle itself—the rationale behind this photographs is barely visible, relegated to the background. Marville’s broader ambition was to capture the topography of Paris prior to the transformations dictated by Baron Haussmann, which aimed to create major axes for circulation, punctuated by emblematic buildings. Thus, the fate of the streets surrounding the Halle was more precarious than that of the Halle au Blé itself. The creation of the rue du Louvre on one side and of the Halles, designed by Victor Baltard, on the other, added open space around the Halle, giving it room to breathe, and established its position in the urban fabric. Historian Jacques Hillairet, author of the Dictionnaire historique des rues de Paris [Historical Dictionary of the Streets of Paris], described the neighboring streets as being “of ill repute.” They included: rue Sauval, rue des Vannes (removed in 1934), rue Oblin, rue de la Sartine (removed in 1888), rue Mercier, and rue Babille (removed in 1886). Positioning his camera along the central axis of each of the six streets that extend from the Halle au Blé, Marville showed glimpses, or slices, of the building itself. Turning his camera away from the building, he captured the rues Babille, Oblin, and Sauval. In the circular rue de Viarmes, he focused on the curvature of the Halle and of the buildings facing it, though without showing a significant portion of the historic structure.

Along with the streets, the paved roads, and the facades of buildings, Marville also represented the neighborhood’s bustling activity: carts, objects hanging from shopfronts, piles of bags tucked behind the arcades of the Halle. A rare human figure occasionally puts in an appearance. Looking at his images, it becomes clear that the urban fabric is so dense that from the street, Parisians would have been unable to see the Halle au Blé in its entirety, and certainly not its cupola, unless they were to climb onto the roof of a neighboring building.

This soaring viewpoint was sought out by Henri Godefroy in 1885, either to fulfill a commission or compelled by his own curiosity. At the time, renovations of the Halle au Blé, which had closed in 1874, had recently begun. From the top of the neighboring Église Saint- Eustache, only a dozen or so meters away, Godefroy succeeded in showing, not the entirety of the Bourse, but as much of it as possible. Pointing his camera downward in the direction of rue Oblin, he was able to capture both the cupola and the way in which the narrow streets of the First Arrondissement are organized around the Bourse. A careful examination of the image reveals that the conversion of the building for its new function had begun, as the cover of the cupola has been partly dismantled.

Several lesser-known photographers also captured the transformation of the building—a transformation that began with a destruction. Architect Henri Blondel maintained one of the two rows of arcades and thus the circular shape of the building, which he hollowed out completely at its center. Above, he also preserved the cast-iron structure of the cupola, which he stripped down to fully reveal its skeleton: the once opaque cupola, located at the center of six converging streets, became transparent.

An image by an unknown photographer, taken from the rue Oblin, shows bystanders gathering on either side of the street to examine the building. They are the privileged witnesses of the impressive spectacle unfolding before their eyes: the top of the Halle, once opaque, has now been rid of its cupola. Another photograph, this time taken from within the building, captures the most intense moment of this demolition. With rubble still to be cleared, the site resembles a ruin. This photograph also allows us to understand the organization of the work site. All the personnel working there—construction workers, foremen, engineers, architects—stand still for a moment, staring at the camera. Behind them, the double row of arcades of the ancient Halle au Blé are clearly visible. Emonts partially showed the iron structure of the cupola in a photograph taken from the rue des Deux-Écus on August 5, 1887, then revealed it in its entirety from inside the building, on August 22. During the early twentieth century, after the building had reopened as the Bourse de Commerce in 1889, photographers continued to show an interest in the shifting and fragile topography of the area. Eugène Atget, the father of modern photography, well-known for having captured the transformations of “Old Paris” into a modern city, also photographed the building from the rue Sauval, as Marville had done forty years prior. He wasn’t interested in recording the appearance of the building, of its main façade on the rue de Louvre, but rather in capturing the spirit of an ancient street that has not yet been fully destroyed. For Atget, the Bourse is fragmentary, seen in glimpses at the end of the street, as the Halle au Blé had been in Marville’s images.

At the request of the Commission du Vieux Paris, Henri Godefroy returned to the top of Saint-Eustache once again, taking more views from the same position as he had done in 1885, to show how the urban fabric around the building had been destroyed then restructured, ventilated.

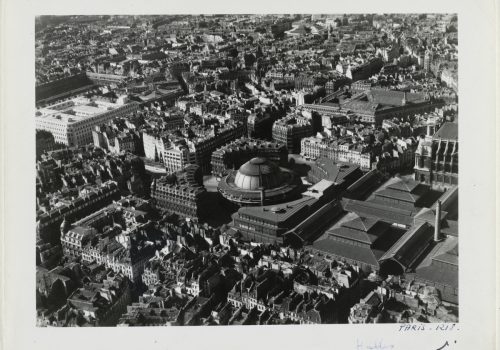

The results of this reconfiguration is best seen in Roger Henrard’s aerial image from 1949, in which the round Bourse presides at the center of a square configuration of buildings that open onto three streets, with the rue du Louvre to one side and the Pavillons Baltard on the other. Looking at Henrard’s photograph, we automatically think of the future destruction in 1971, of the Halles, which, despite the polemics it provoked, made the rear facade of the Bourse more visible, giving it the appearance it has today.

Article published in the eleventh issue of the journal Pinault Collection, October 2018 – March 2019

www.revuepinaultcollection.com