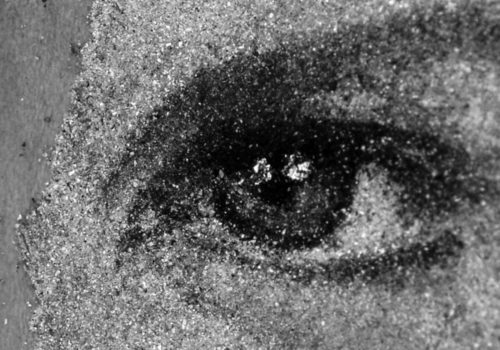

Heide Hatry (born 1965) is a German neo-conceptual artist based in New York. Her work, often either body-related or employing animal flesh and organs, has aroused controversy and has been considered horrific, repulsive or sensationalist by some critics, while others have hailed her as an “imaginative provocateur”. She has been commemorating lost loved ones with cremation portraits since 2008. To create the likeness of the deceased, the German artist adds the ashes, piece by piece to layers of wax.

What made you decide to create this project?

I have to say that, first, I didn’t conceive the project as art. It began as the totally unanticipated way that I came to terms with death and with grief in my own life, and when I realized what potential it had and that I could share that, I was happy in the same way I am to share my art, but I only came to look at it more generally and to configure it as an art idea, and as an art idea that has taken on profound dimensions, in some way radically questioning the nature of our relationship to the art-work, while returning to what might be seen as a primordial feeling for both matter, in the most basic sense, and for the image as an essentially social, while deeply emotional artifact, as a result of my own painful experience.

When my father died 25 years ago, in what seemed to me at the time to have been suicide, I was devastated, and it took me quite a long time even to be able to think about him without breaking down crying. Then, in 2008, one of my closest friends committed suicide. I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t been aware that he was feeling so despondent that he could do that, and not only was I inconsolable, but all of the unresolved pain of my father’s death also came back to the surface. I felt paralyzed with grief.

In Germany, the ashes of a cremated person must be buried, so I had never encountered the practice of preserving, or sometimes scattering, the ashes of deceased loved ones before I came to America, and it was, by chance, only a few weeks before my friend died that I had been allowed to look into an urn that contained the ashes of a friend’s deceased wife. That experience touched me deeply, and maybe because of it I had the sudden idea that I needed to make portraits out of my friend’s and my father’s ashes. Probably that says something about my deeper motivations as an artist, that I think that death can be conquered by art, or that it can heal the worst emotional pain, but the fact is that even as the idea came to me, in a sort of revelation, I already started to feel a calm arise within me. Over the several months it took to figure out a method of using ashes to make their portraits (as I implied, I didn’t have access to their actual ashes, so I was using a substitute, as I tried to discover a technique that would work) I engaged in an almost constant dialogue with them, often out loud, and even crying or yelling. By the time I had made their portraits, not only was my grief dispelled, but I felt like they were somehow there with me, that there was a presence that goes way beyond the power of art when I was with them. It reminded me of the relics of saints in the Catholic church or the humble glow of an Icon, which is often so much more powerful than even great works of religious art because believers know that it has been blessed and that they are being protected by the saint it depicts.

Being an artist, I naturally thought that the effect was caused by the, in this case very lengthy, process of making the portraits, but when a friend, whose mother had died when he was still rather young and with whom he felt he had a totally unresolved relationship, one that was cut short before they could know each other in the way he wanted, asked if I would make a portrait for him as well – with her actual ashes – I discovered that he had the same almost preternatural experience, both of the presence of his mother, and of an indescribable calm and consolation. That’s when I thought that this was a comfort that I could offer to others as well. And it turned out that I knew quite a lot of people who had ashes of loved ones that they felt were almost a burden, or were being disrespected, or shunted aside, by simply being stored in an urn or a box, and over a number of years I made portraits for some of them as gifts, always finding that their relationship to their beloved changed or was enriched in a range of interesting ways just by having this renewed contact with what they knew was the physical residue of the actual person they had loved.

How do you choose the people you want to create portraits for? Do people come to you to request these pieces?

I didn’t really choose the particular subjects, except to the extent that I was speaking to friends or people I learned had suffered a loss and telling them about my experience and that of others for whom I had made portraits, but it does strike me that in a world in which many more people are being cremated than ever before, we are more often in the company of what remains of our beloved long after the immediate exigency of attending to the body or even of coping with the pain and grief that frequently renders reflection impossible and which has typically dictated that we simply adopt common social practices without examining them, has subsided. So I think that in some way my discovery happens to suit the times, even as it obviously reflects a long cultural and perhaps even primordially human tradition. In fact the great art historian Hans Belting, among others, thinks that the origins of portraiture had exactly the purpose that my project envisions – to keep the dead among us and clear in our minds, in some way still in relationship to the kinship group, even exerting a force among us with their presence. For me, such a process seems clearly better than hiding the dead away in an urn or spreading them to the winds. Memory is always better than forgetting: it is the basis of everything important that is human.

More pertinently, though, a lot of people feel something like despair when the people they loved die, as if a part of them has died, too, or that they have suffered a horrible trauma. Knowing that the person is actually right there in front of you, as if seeing you as you look at him or her, has a powerful effect. The friends for whom I made a portrait all told me that they also sometimes talk to their beloved one, just as I do with my father and my friend.

Of course, a lot of the people for whom I made the first portraits are artists or people for whom art is an important thing in their lives, so for them the visual impact of the work is also very powerful, and they are used to having a deeper relationship to images than to something that is simply functional or decorative, and they also tend to hate waste, I mean to hate to incorporate objects in their lives that don’t express some sort of meaning. In addition, the people who typically want this are people who had a profound and deeply loving relationship to the departed, and they feel this as an act of reverence to them and a memorialization of their relationship and their love. They don’t ever want to forget them.

Still, it’s not something everyone would want, and plenty of people find it an uncomfortable prospect even if their relationship to the deceased was not fraught or problematic. That said, there are also people who have found it compelling in spite of their deep qualms about using the ashes of people they loved. One of the people whose husband’s portrait is included in the exhibition always tells me that while she is horrified by the project, she has also felt healed by it, and I really admire her for engaging these complex feelings. But so far, most people who see the work find it invigorating or recognize the obvious respect that animates it than find it frightening or creepy. I sense a turn in the general rejection or fear of death that has characterized our modern relationship to it. Look at all of the books that have been published about death in the last decade, an astonishing number, and groups, like reading groups, that get together to discuss aspects of death, the so-called “death cafes,” or even programs that discuss death with children in schools. And I think this is a great way to help bring that suppressed curiosity, or “socially inappropriate” but totally natural and healthy fascination into the open, and into normal life, again, after a very long and counter-productive period of repression.

Has this project made you more interested in death as an art form?

I’m not sure I know quite what you mean by “death as an art form,” although it certainly sounds evocative – De Quincy’s On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts or Stevenson’s “The Suicide Club” spring to mind – but I have very much worked with death during the 8 years I’ve been engaged in this project, and I’ve learned a lot, for example, that we all have to die – including me. Of course I knew that before, but there is a huge difference between “knowing” and actually being aware of it. And I think this difference is what makes death such a huge taboo, especially for people in the US and other “civilized” countries. To really understand that we have a few years on this planet and that then everything will be totally over is just too painful for most of us, and since death is unavoidable, it seems to be easier, and maybe more practical, to avoid thinking about at it. Personally, I’m trying to cope with that pain, to get used to it like to a chronic condition and use it to remind myself of how beautiful life is and to want to live it to the fullest.

One of the not necessarily empty platitudes about art holds that it is all about death, even that it owes its existence to the fact of death, much as the philosopher, Jacques Derrida, could contend that “all of his writing was about death.” And the Buddha, among many others since, quasi-paradoxically opined that the meaning of life is death. In some ways, it is more difficult not to be interested in death, even without trying than it is to be free of the thought of it. Since, however, in a way that cannot easily be said of much other art, the very substance of Icons in Ash is death, and in some respect I see myself as speaking for death, or rather letting it speak on its own account, giving it a voice uncolored by the civilized history of art or thought, I am profoundly and very personally attuned to this empty and very impersonal “thing.” I think that much of the quiet force of Icons in Ash comes from the fact that we feel the void even as we know we are looking at someone we once knew and perhaps loved. Death has the human face it has been missing for such a long time.

Could you talk a bit about your process, about your workflow in creating each piece from start to finish?

I use three different techniques to make my ash portraits, all of which took a lot of trial and error to perfect – in my many experiments I generally used animal ashes from cremated pets that hadn’t been claimed by their owners. The first, and the one I’ve spent the most time both developing and practicing, is essentially a mosaic technique, which requires individually placing thousands and thousands of discrete particles onto a bed of wax to create the likeness, working from black-and-white photographs that the family or friends have chosen for the portrait. The obvious difference from the mosaics you might know, say the famous ones in Ravenna, is that my fragments are not really visible as individual “stones,” but are tiny particles, like dust or pigment that create a subtle dimensionality when they’ve been arrayed on the wax.

Because the ashes are pure bones and therefore of only one color, I also use white marble dust (as a symbol of death) and black birch coal (as a symbol of life) to get a palette ranging over different shades of grey. This is, as you might imagine, an extremely painstaking method, and I am hunched over the work sometimes for weeks, applying these microscopic fragments with the tip of a scalpel. It is like reconstructing a broken image, which is in fact where the word “mosaic” comes from – Moses piecing back together the tablets of the Ten Commandments that he had shattered in anger.

I also use a more painterly, but still methodical and highly repetitive, or meditative, technique, in which I draw many layers of very diluted ink onto either an emulsion of ashes and binder, or on a surface of pure ashes. These look almost like photographs, but have a much deeper and textured feeling because of the layering of the drawings.

And, finally, because I realized that so many people who would like to have such a portrait can’t afford an image that is so time-consuming to create, I developed a photographic technique in which I can recreate a photo on a surface of pure ashes or, again, on a surface bearing an emulsion of ashes and binder.

The portraits I have made so far are always approximately life-size, which I think supports the feeling that the person is actually there, and I recess them in a shadow box, which gives a sense of deeper dimensionality, as well as a distance that I think subtly reflects the changed state of the subjects’ existence, as well as of our relationship to them.

This is a conversation with the deceased – an homage to their legacy. These are their very ashes made into a portrait of themselves. How did it feel to start using ashes of people you didn’t know to create such long-lasting pieces for their loved ones and for yourself?

I like how you put it: “a conversation with the deceased.” That’s exactly what it is, and an homage to their memory!

When I started to develop this as an art idea, I had strong and strange feelings to touch the ashes of human beings, but I suppose that uppermost among them was the feeling that this substance was something precious and that, unlike almost every other action one might take as an artist, I had to be extremely careful and specifically about the material itself.

But the far more disturbing aspect of the matter as I began offering to make portraits for others was the idea that I, as a German artist, making something out of human ashes, would involuntarily and almost inevitably conjure thoughts of the Nazi atrocities for many viewers. I was so troubled by that possibility that I had to give up the whole project for several years, not seeing how it wouldn’t cause pain or anger rather than the solace that I intended. It was only after I researched specifically what the Nazis actually did and what they intended that I could resume it, because I knew that my purpose was exactly the opposite of theirs: where they wanted to obliterate a whole people and make it as though they had never existed, to destroy them, and eliminate every trace of them, I am remembering, preserving, honoring, and making present what is lost to us. To me, this is an act of reverence.

Of course it’s still strange to work with a human being’s ashes, and sometimes I have a very hard time to continue working and need a break – that actually happens more often when I am working on somebody I knew – just because it is so intense to be aware of what I am doing. On the other hand it is a pure labor of love and I am rather trying to think about putting the bone particles back together, animating, in a way, a person who has died, than thinking that this is a dead person. There is simultaneously a frustration and an ecstasy in this practice, which I think exemplifies the frustration and the ecstasy that has always characterized art: we are desperate to make whole what can never be whole, to make sense of what never makes sense in actual life. This is where art is at once a greater truth than life, and an inevitable, if inadvertent, lie that has always excited a certain distrust among the practical and the earnest. I believe, however, that this seemingly irresolvable tension or aporia is a consequence of the denial of death to which most civilization has been so fervently devoted from time immemorial, and in Icons in Ash, by materially putting the fact of death before us in its simplicity and its specificity, we can begin to strike an understanding that neither diminishes nor overreaches its subject.

Describe your creative process in one word.

Love.

If you could teach one-hour class on anything, what would it be?

How to follow your dreams

What is the last book you read or film you saw that inspired you?

I am usually inspired by nature or art exhibitions, but the last book that inspired me was what I am reading right now: Death: An Interdisciplinary Analyses by Warren Shibles (Language Press, Whitewater, Wisconsin, 1974).

What is the most played song in your music library?

Black Star by David Bowie, sung by Amanda Palmer and Anna Calvi.

How do you take your coffee?

Lots of steamed and frothed almond milk with a few drops of espresso.

Interview by Hallie Neely

Hallie Neely is a writer specializing in photography based in New York, USA.

Heide Hatry, Icons in Ash: Cremation Portraits

December 8, 2016 — May 12, 2017

Ubu Gallery

416 E 59th St

New York, NY 10022

USA