Situated along Switzerland’s majestic Engadin valley lies a sleepy village of no more than 800 residents known as S-chanf. It is here, amongst the historic houses and Romanic architecture, that a new outpost for modern and contemporary art has emerged: 107 S-chanf, the result of a collaboration between Zurich’s Jablonka Galerie and art dealer Aroldo Zevi.

In the lower valley lies St. Moritz, known as much for its jet-set lifestyle as for its myriad galleries which draw an elite crowd of art connoisseurs each season. As early as the 1980s, St. Moritz became a destination for buying art, beginning with the Zurich dealer Bruno Bischofberger who—with keen foresight—built a studio underneath the Survretta lift and invited artists such as Francesco Clemente and Jean-Michel Basquiat to show their work. The nearby town of Zuoz, an ancient village with a population of less than 1300, has also became a go-to place for art lovers with the establishment of Galerie Tschudi in 2002 and Galleria Monica de Cardenas in 2006. Most recently New York’s Pace Gallery opened in an impressive five-floor twelfth century house renovated by renowned architects Ruch & Partners. The addition of 107 S-chanf this past February, the latest gallery to open in the region, is housed in a three story minimalist space tucked away within a warren of cobblestone streets. Although easily missed as no external sign indicates its identity one’s search is well rewarded as once inside there is no mistaking its potential as a platform for modern and contemporary art.

The exhibition on view at 107 S-chanf, “AVEDON WARHOL Portraits,” marks the gallery’s inaugural show, running from February through March, and echoes the artistic milieu shared by Richard Avedon and his contemporary Andy Warhol in the latter part of the twentieth century when both artists had already achieved fame and fortune for their work, yet seldom crossed paths professionally. The focus is primarily on their photographic portraiture, with exception given to a selection of large-scale portrait drawings that Warhol created between 1976 and 1984 found on the ground level, including subjects such as rock legend Prince, style icon Diana Vreeland, and President Jimmy Carter.

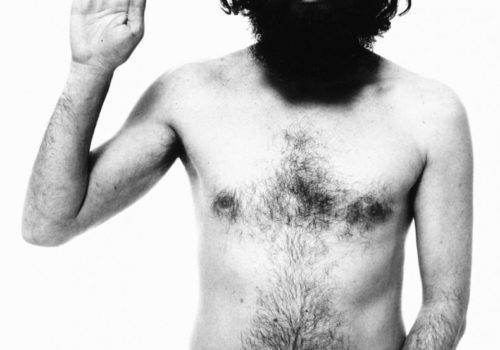

It is the second level however that stands out as it is here we find Warhol and Avedon presented side by side as portrait photographers. Although Warhol is not primarily classified as a photographer, photography was central to his artistry and portrait photography in particular provided the basis for many of his most well-known silkscreens. Avedon’s own pursuit of self-fulfillment entailed dismissing the half-century of magazine work he carried out for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue as no more than a day job. He instead chose to emphasize his portraiture which he conceived, controlled and executed in his own exacting terms, recording American society and culture for posterity. The images selected for this portion of the exhibition depict their subjects au natural, stripped bare, in all their imperfections, lumpen and wrinkled, bloated and spotted, as in Avedon’s 1975 candid photo of a rugged-looking, yet weary-eyed Robert Frank, dog in tow, or of a naked, hairy and full-bellied Allen Ginsberg from 1963, with right hand fittingly or perhaps symbolically raised as if in protest. Most poignant here is Avedon’s 1969 photographic portrait of Warhol showing his scars and sutures following a near-fatal gun-shot wound. This is not the Warhol we know, who often eradicated his flaws in print for the sake of perfection and who once commented, “I love plastic. I want to be plastic.” This is the man behind the façade he had so carefully devoted his life to creating.

Avedon’s portraiture continues into the next room with “The Family,” occupying the entire stark-white back wall of the second floor. Commissioned by Rolling Stone in 1976 to cover the presidential primaries and campaign trail, Avedon spent several months photographing soldiers, potentates, and ambassadors. The result was sixty-nine black-and-white portraits depicting mostly white, male members of American political and elite society—the Kennedy’s and Rockerfellers, as well as Presidents Carter, Reagan and Bush to name but a few. All have been neatly arranged in four rows and flanked on either side by Warhol’s more glamorous silkscreen images of Italy’s industrial tycoon, Gianni Agnelli and his wife Marella. In contrast to the bold composition and emblazoned color of Warhol’s Agnellis, the style of “The Family” is formal and minimalistic, yet intimate. Avedon was fascinated by age and this is evident in his refusal to use flattering, chiaroscuro lighting. Instrumental in doing away with traditional portraiture that tended toward idealization, Avedon captured every age spot and skin fold, a technique reflected as much in the portraits that make up “The Family” as in his images of archetypal bohemians from the worlds of literature and art.

The selection of photos by Warhol, found in the back, alcove-like room also reveal the same rawness and honestly as those by Avedon. Although he advised to “always omit the blemishes—they’re not part of the good picture you want,” Warhol’s Polaroids reveal a non-idealized reality that is instead elemental and exposed. Here we find a snapshot from 1979 of Warhol’s favorite writer Truman Capote donning a fedora and an air of cool with cigarette in hand. Despite his laissez-faire attitude Capote’s age and reliance on drugs and alcohol are revealed in his sunken features and colorless mouth, his piercing blue eyes barely visible behind his heavy lids. The most interesting piece in the room however, is a portrait of Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola painted in 1974 at the Factory and taken from an earlier photograph. The silkscreen image is faint and faded under layers of paint which Warhol created using his fingers, perhaps a reference to how he viewed his then-deceased mother: in the abstract.

Avedon once posited, “If each photograph steals a bit of the soul, isn’t it possible that I give up pieces of mine every time I take a picture?” The photographs in “Avedon Warhol Portraits” are as much about the artist as they are the sitter. In each we catch a glimpse of the artist himself, radical and raw, dismissive of convention. Warhol considered himself ugly but he also saw himself as a mirror, and his camera lens became the reflective device he used to capture his various guises. If the eye of the camera is the ultimate window to the soul then these images are mirror reflections of their creators, stripped bare, for all the world to see.

Avedon Warhol Portraits

107 S-chanf

Bugl suot 107

7525 s-chanf

Switzerland

tel +41 81 8540475

[email protected]