A Determined Collective

Written by Taylor Hall

Taking its title from the Uluru Statement of the Heart, ‘From All Points of the Southern Sky’, curated by Ashley Lumb, taps into the momentum and passion of the 13 artists included in the show and their determination as a collective. The statement invokes the Yolngu concept of ‘Makarrata,’ which translates as the coming together after a struggle. This sentiment is at the heart of the movement toward recognising Indigenous Australians in the nation’s constitution and acts as the anchor point for all thirteen artists gathered within the exhibition. Each artwork featured within ‘From All Points of the Southern Sky’ is a distinctive cry for collective action and shared responsibility.

Central to the exhibition is the quest for indigenous rights and their intrinsic link with Country. The struggle referenced by the Uluru Statement of the Heart is the struggle for indigenous rights and reparations, which despite many half-hearted and misdirected attempts from the Australian government, is a fight far from over. The exhibition highlights the importance of intrinsic cultural links between indigenous peoples and their Country, referencing a broader struggle contended within the exhibition that is wholly environmental.

Showing at the Southeast Museum of Photography in Daytona, Florida, the exhibition brings into focus photography from Australia and Oceania, reflecting broadly on the contemporary socio-political issues of the region. It speaks to an age of international connectivity that the American audience within Florida (as well as the broader global audience) can empathise with the unique circumstances of global climate change and the present-day impacts of neo-colonisation. Therefore, despite exploring issues deeply pertinent to Australia, ‘From All Points of the Southern Sky’ acts as a universal call to unite in the face of adversity.

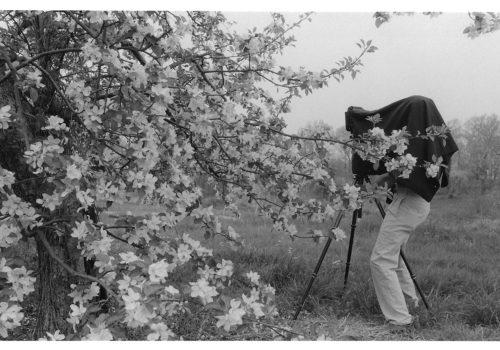

At the forefront of the exhibition’s discussion of Indigenous civil rights is the urgent need to critically address the devastation caused by the 19th century camera lens. By resurfacing and reworking archival imagery, artists such as Leah King Smith, imbue an Indigenous voice within an originally colonial document. An Australian artist of Bigambul and British descent, King Smith combines single-exposure photomontages with 19th century photographs of Aboriginal people taken by European photographers. The artist then superimposes her own photographs of the landscape, occasionally painting over parts and rephotographing them. The inclusion of King Smith’s Patterns of Connection series (1992) within the State Library of Victoria Picture Collection therefore interrupts imperialist mechanisms of historicization. For King Smith, the duality of these 19th century photographs serves as both a witness to the reality of past brutality as well as evidence of the archives capacity to revise and recontextualise the photographic gaze. Though they are read in the present, King Smith’s photomontages pull on threads from a plethora of ‘times’, urging one to see the photographic object as alive and full of possibilities.

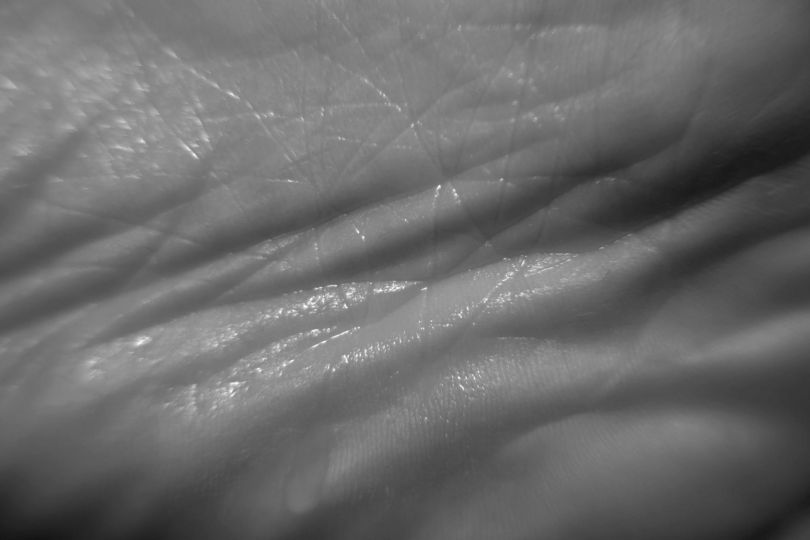

Similarly, Peta Clancy, a descendent of the Bangerang people from south-eastern Australia, reworks past colonial narratives to provide an authentic and ethical approach to reparation. Clancy’s work Undercurrent (2019) was sparked by her research into her Bangerang heritage and a Victorian massacre map, showing the locations of known mass killings of First Nations people by European colonisers between 1836 and 1853. Clancy visited massacre sites on Dja Dja Wurrung country and collaborated with the Dja Dja Wurrung Traditional Owners and community, taking photographs of the landscape over time. Clancy cut into the physical images, layering one view of the landscape with another, each perspective differing in its distortions and muted tones of pink. Within her series, the massacre sites act as a stratified archive of grief. Despite the changing environment (the bank of the river becomes submerged), what lies beneath the surface of the site and is harnessed by Clancy, are the atrocities “remembered” by the physical landscape. Clancy’s act of dismembering photographs taken of the site exposes the wounds and internalised grief held within the Indigenous psyche as well as the land.

Undercurrent’s outlook on the land as a witness and an active body subjected to the ‘ugly’ parts of history is reflected in Stephen Dupont’s series Fire (2020). Dupont’s evocative images document Australia’s most catastrophic fire season, ‘The Black Summer’ of 2019 and 2020. For many Australians, the intense orange, red and charred black colourations that are shown to consume Australia’s flora and fauna inspire deep feelings of loss, heartache and grief for the environment. It is important to note that there is no equivalency between the ancestral, collective grief of Indigenous Australians and the emotions provoked in many Australians from the loss of landscape and livelihoods caused during Australia’s Black Summer. Lasting over 240 days, the fires burned 46 million acres of land and killed one billion animals. The Black Summer was a boiling over of decades of environmental destruction, government negligence, and evidence of our Anthropocene reality. As the dust settles and Australians emerge from what felt like an unending environmental backlash, what we are faced with is a grieving nation and its land.

A significant portion of this grief can be drawn from the guilt that these fires, and more broadly, climate change, are a consequence of modern civilisation’s exploitation of the natural world. For the first time, humans have become the dominant cause for environmental change. Despite being the catalyst for change, we now have a horrifying lack of control over the future of our merciless Sunburnt Country. It is images such as Dupont’s that bear witness to the destruction incurred by our country and its people, effectively uniting us all in acknowledging the weight of that loss.

Adopting a different approach to “truth telling”, Anne Zahalka challenges the stereotypical, picture-postcard representations of the Australian landscape. Zahalka explores the often Anglocentric photographic record by hand-colouring and digitally embellishing archival photos of museological dioramas. The result is a bizarre and satirical collision of the commercialised picturesque landscape and the realities of the burgeoning climate crisis. By adopting a pastiche-style approach, Zahalka’s use of taxidermy animals and an oversaturated landscape lend itself to a vision of the uncanny valley. This method is apt when we consider our current unfathomable environmental reality. The sheer loss of flora, fauna, homes and lives, not to mention the environmental impacts that future fires may bring, seems to exist in the realm of the unbelievable.

All thirteen artists within ‘From All Points of the Southern Sky’ come to the realisation that the land, as well as its people, are in a similar and constant cycle of damage and repair. What is central to the exhibition is the stark reality we face in both the battle for Indigenous civil rights and global climate change, as well as our urgent need for collective action to heal the wounds of the past. ‘From All Points of the Southern Sky’ asks us to bear witness to this grief and turmoil in order to come together and unite for this struggle and those on the horizon.