Setanta Books publishes A Country Kind of Silence by the photographer Ian Howorth. He sent us this text by Harry Gallon.

Britishness is a collage of cross-cultural signifiers. Complex and simple, sad and beautiful, known and forgotten. Things that have their own language, their own patterns of tradition and ritual that intermingle with the day-to-day of basic need. A cup of tea. Windbreakers tripping over on a beach. A line of telegraph poles marching into the distance. We see in so many moments a vision of Britishness easy to acknowledge. But that validation is becoming more polarised with each decision we make to embrace or ignore, rather than understand the reasons for flag waving when so few have the means to get by.

Contemporary Britain is enveloped in a cultural nostalgia that has engulfed all facets of life, from departments of state and local authorities, to marginalised and rural communities squeezed by cuts and forgotten. In A Country Kind of Silence, place and landscape is deconstructed. Each separate building, road, overhead wire is painted as though bones of a skeleton, co-dependent and togetherness built into their function.

There is choice in where humans place their own bodies, but not always agency: geographical boundaries and economic circumstance bind us to localities and lifestyles we may otherwise eschew. People become objects placed by powers greater than they are—policy, polity, centuries of migratory patterns, wars and slave trades that still have an impact on where our lives are today. The places captured in A Country Kind of Silence speak through those centuries, the passage of time transforming their cultural value and language so that place changes from constant to character, evolving to accommodate the different meanings we need from them. A bench at a bus stop. A phone box. A Union Jack. The British, specifically the English, may be afraid and resistant — stuck in their ways, shy of upheaval and resigned to being treated with disdain by their leaders — but therein lies a hint of their truest nature, where resistance means to keep going and fear is a placeholder for what the unknown becomes when it is met. Place exists as the altar of our everyday experience, witness to the marriage of surprise and sadness — of loss and longing merging to share space with joy, beauty and belonging across a landscape scarred, brutalised and enclosed over centuries, individual identity merging with that of nationality, so that community becomes, at least in certain eyes, a tired, outdated word, but one that still remains authentic.

Our value as individuals may be inherently linked to our homes, houses, cars, footpaths and places of leisure, but our collective identity as Britons has been forced to feed on a past romanticised. The value of the things we interact with, which together define our communities, has been bastardised by the need to link them to not only that past, but to a specific, cleansed part of it. But what is their value besides that which is forced upon them? Meaning is garnered from use, from sentimentality, from love and the realness of living memory, and what is remembered can exist without what is presented. Nostalgia is based on change — from old ways, to new; from a past that is believed to have been good, to a present that is known to be hard, but which we get through with shared experience. In memory we refind things lost to the physical world — pets, places, friends, lovers. To change as time passes, as these things become lost to that world and our experience within it, is to redefine our physical stake.

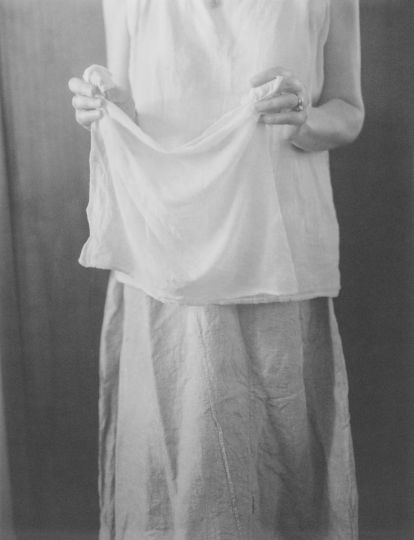

What is captured here is something without physicality; something supernatural. A feeling, almost—like standing outside a house and listening to the inhabitants sit down for a meal, their cutlery scratching the dishes, their laughter and admonitions, their coughs, their sneezes. Then, upon opening the door and entering, finding their food half-finished, lipstick on the rim of a glass, crumbs around the legs of a chair, but not finding the inhabitants there. Rather, what fills that room is the warmth, the gentle quiet of their presence, as though spying a ghost which, having felt eyes upon it, promptly vanishes into a place the living cannot access. One of shadow. And light. And deep, natural energy of the kind that makes plants grow through abandoned cars, birds flock and people stare out to sea.

In A Country Kind of Silence the artist questions linearity by exhibiting time as multi-layered, so that past and present exist together, all at once — a fragmentation of lived experience superimposed by the subconscious into our dreams, painted with the colours and textures of a world built to last, rather than one based on the constant need for change, and the dependency on consumption that it demands. That is, a world that humankind has made disposable; one that we cannot picture a future for — at least, not right now. Modernity was — is — meant to free us and liberate us to live more leisurely, see the world, meet new people and enjoy a life of convenience rather than hardship. But the cost has been high. The Britain captured here is a mire of contradiction, on the one hand being pushed towards a wealthy, fair future by corrupt politicians spinning platitudes about equality and progress; on the other becoming ever more deeply entrenched in the romanticisation of empire and wartime – eras that almost no living people can remember, but which they cling onto for dear life.

Whilst nostalgia reigns, modernisation cannot be completed, and therein lies the contradiction of Great Britain — why attempt it at all? Some of the places featured in A Country Kind of Silence remain locked, physically, in their pasts, but retain the same functionality. Some are so stuck that they have begun to rot away, useless, now, to a community robbed of the means to update them. In many cases, the need for change as deeply personal does not have to be reflected in the physical. A wood-panelled boardroom is still a boardroom — a place to sit and discuss business or legislation. But as time passes and individuals change, even the utilitarian gains a value based on sentimentality. Nostalgia itself changes, from being just the idea of what a once-powerful country was, to what individual communities could be. In A Country Kind of Silence, place, providing home for the many, becomes body, which sustains the one. It isheld up by the skeletal set pieces deliberately chosen by the inhabitants—a bench at a beach, delivering a view. A bench at a bus stop, providing a rest. A caff. A salon. A crumbling seaside town.

Transcending change, be it for reasons of neglect or simple preference that they remain the same, the role of place becomes captivating to an artist whose relationship with identity, belonging and locating in Britain a home is both fluid and tumultuous. Collective cultural memory is learned, not felt, and in this project the artist celebrates that process — from the childhood teachings of his father — practical, considered—to the slow, meticulous detail with which he approaches his work — following hints, covering ground in quietness, ears pricked and eyes open to what might be hiding in the peripheries, waiting to present itself rather than be dug out. The need for genuine experience parallels the authenticity of what is captured — what is tangible, what is unchanging, what is a form of lifeblood coursing through each of us — and the brevity of this project cannot be ignored.

To feel close to these places is an exercise in reconciliation to a life of internal solitude and searching. Not simply visiting, but staying, eating, speaking — an attempt to reflect on the need to settle in a land not the artist’s own.

It is a struggle to lay down roots in a world obsessed with borders, but outside of tabloid sensationalism and political manipulation, the intricacies and eccentricities of what community is at its heart becomes an anchoring force — a confirmation that the roots are already there, and that in order to sink them all you have to is stand still for a moment, and be present.

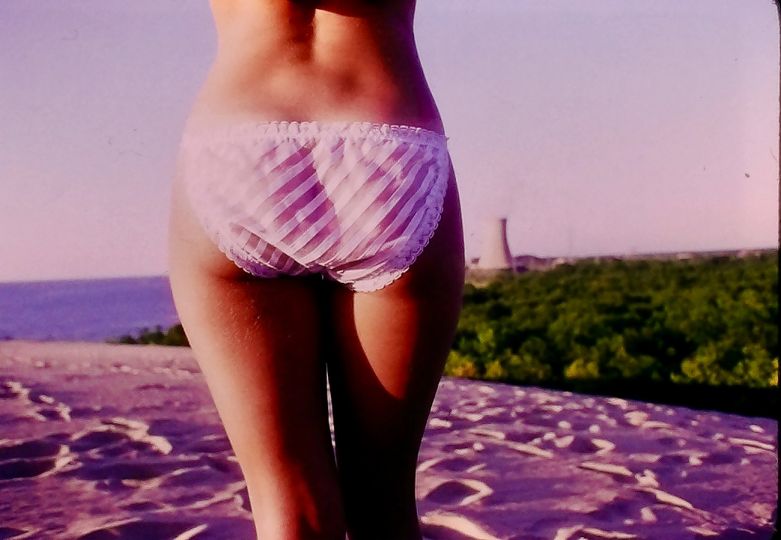

This is a Britain of distant summers. Of longing. Of homesickness for somewhere never visited; for a place that never existed but can be felt deeply and almost seen, somewhere far out to sea. Blue heat and painted sunsets. Dry grass and patio ant nests. Cracked dog shit. Torn flags. Distant chaos. Stoic silence. The sweltering exhaustion of trying — just, simply, trying, day after unforgiving day, to make sense, but to also know when it’s enough.

Harry Gallon

Ian Howorth : A Country Kind of Silence

https://www.setantabooks.com/en-us/products/a-country-kind-of-silence

Setanta Books

www.setantabooks.com