Over the following decades, the rediscovery of both photography and certain photographers took on ever greater dimensions. In 1981, a film entitled Poete et pieton (Poet on Foot) was made about Robert Doisneau by François Porcile and the book Ballade pour un violoncelle et chambre noire, the photographic marathon that he had run with his friend Maurice Baquet, finally saw the light of day. Greatly limited in his activities by the long illness of his wife, Pierrette, Doisneau nevertheless had to cope with numerous demands on his time. New generations rediscovered these images gleaned from the manipulation of chance and unpretentiously made for the pleasure of the eye. Publications, exhibitions, and distinctions rained down on him. In 1983, the Centre National de la Photographie, founded by the Minister of Culture, Jack Lang, and headed by Robert Delpire, published his photos in its Photo Poche collection. That same year, the Grand Prix National de la Photographie, created in 1978, was awarded to Doisneau in succession to André Kertesz.

Doisneau’s return to eminence was given concrete form in the invitation to take part with fourteen other photographers, including Gabriele Basilico, Raymond Depardon, Sophie Ristelhueber, Holger Triilzsch, François Hers, Pierre de Fenoyl, and Tom Drahos. in the DATAR Photographic Mission, whose object was to define the state of landscapes, work, and living spaces in the 1980s France. By personal inclination – but also because of his wife’s fragile state of health, which meant that he could not leave Paris – Doisneau chose to photograph the Parisian suburbs and their redevelopment. Breaking with his previous habits, he brought off a remarkable challenge choosing color photography and eliminating people from his scenes. “The image should be a simple sign” said Doisneau of these powerfully symbolic images. “It took nothing else than Doisneau’s talent, “writes Roger Brunet, “to set before us in all their garishness (but with what style!) the baroque of Evry, the manpower storage silos of Nanterre and the Disneylands of the poor in Evry or Grigny” Doisneau painted a pitiless portrait of this polychrome suburbia, all gentle colors so that the place seems bearable”, in graphic and stridendly colored images. His sarcastic analysis of a universe that he no longer recognized was a visual indictment and he accompanied it by these radical words: “Starting from the wastlands and the nibbling at the edges of the bungaloid housing estates, men in helmets have made vast clearings in which parallepipeds spring up like mushrooms.

The same volume set vertically on end becomes a tower: laid out horizontally, it becomes a block of flats whose featureless gables randomly display a mosaic Rimbaud or Beethoven. Sometimes one finds oneself in front of a cliff face pierced with simple opening which is a very convenient way of storing the maximum number of working-class families in the minimum space.” Words and images alike reveal and confirm the profound social sensitivity of a photographer exasperated by the vision of these urban deserts.

Doisneau was restored to his true milieu by the commissions that he received from the municipalities of Saint-Denis and Gentilly. There are, he found, at least some signs of animation. of life. But he was beginning to feel a profound disenchantment. In the places where he had taken his first photographs, “concrete has replaced plaster panels and wooden hutments. Nothing any longer holds the light.”

Hence, sadness and solitude emanate from these works. Even Paris and its Parisians were changing: “Photographers are now regarded with suspicion. I am no longer so welcome. The magic is broken. It is the end of uninhibited photography of those who nosed out buried treasures. The joy has gone out of me.” “The streets have been emptied , drivers scowl from the windows of their aquariums and the only people you meet are those scurrying down the pavement to or from the station or Metro, always belated and frequently aggressive.”

Yet the pressure of his commitments was unremitting. In the fourteen years between 1980 and 1994, no less than twenty four books of varying size were published. From Uncertain Robert Doisneau (1986) to La vie de famille (Family Life; 1993), an entire universe was in the process of rediscovery, in particular, thanks to the photographer and author teaming up with old or new friends such as Jacques Prevert (Rue Jacques Prevert, 1992), François

Cavanna (Les doigts pleins d’encre [Fingers coverered in lnk], 1989), Daniel Pennac (Les grandes vacances [Summer Holidays], 1991), not forgetting A l’imparfait de l’objectif (1989); a major work of autobiography in which Doisneau gives a humorous. affectionate account of his own life. These publications were a major commercial success, manifesting as they did the proximity and indeed complicity between Doisneau and the writers: “I like men who took the trouble to live before writing: Cendrars and Prevert for poetry, and Cavanna, too, who is a grubby kid and learned everything in the school of hard knocks. I prefer that kind of writer; they bring back to the surface the harmonics that I stored up in my childhood.”

Other works brought complementary intuitions lo bear on the work of Doisneau, such as Les enfants de Germinal (The Children of Germinal; 1993), with a text by François Cavanna and photographs by Willy Ronis and Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, and Doisneau 40/44 (1994). The most important of these books was the monograph by Peter Hamilton, Robert Doisneau: A Photographer’s Life (1995), which was published to mark the large-scale exhibition curated for the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, in 1994; the exhibition went on to the Musée Carnavalet the following year. It was an unparalleled popular success, exceeded only by the Doisneau retrospective Paris en liberté (Paris at Liberty; 2006), which was held at the Hotel de Ville de Paris and seen by more than 400,000 visitors.

Doisneau’s charisma inevitably increased the media pressure that he was under, in particular from television and cinema. Very early in his career, Doisneau had been attracted by the magic of cinema and, above all, by the great films of the 1930s. There are clear connections between the poetic realism of 1930s cinema and the photographic corpus that he accumulated over the course of his life: Doisneau was proud to confess the influence. In the company of Andre Vigneau, he had met filmmakers such as the brothers Jacques and Pierre Prevert and heard about Soviet cinematography and Luis Bunuel’s Un chien andalou. “All the same, I must admit that. among my unacknowledged desires, there is, first and foremost , the world of cinema, in which I should so mu~h like to have taken a stroll; yet again, it slammed the door in my face.” “I should Like. if it vvere possible, to try my hand at cinema, I shall look into the matter and cautiously circumnavigate the bait before biting,”

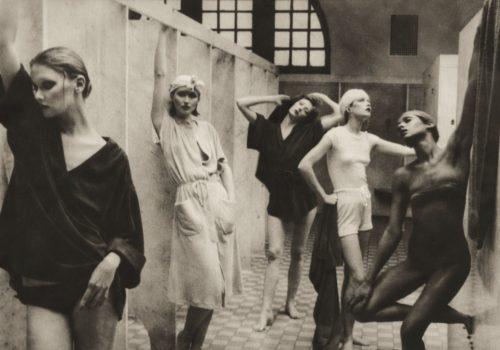

He wrote to Maurice Baquet in the 60’s . Though these ambitions \vere never fulfilled, he was able to enter the cinematic world as set photographer for a number of films, including René Clair’s Le silence est d’or (Silence is Golden; 1945), François Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (Shoot the Piano Player; 1960 ), and Nicole Védrès Paris 1900. With Bertrand Tavernier’s Un dimanche à la campagne (A Sunday in the Country; 1983), he followed the entire shooting and made the acquaintance of Sabine Azema, who became one of the great friends of his final years. During the 1980s, he made some experiments with video, including a short for the Rencontres d’Arles and, in 1993, a little film called Les visiteurs du square. He himself became the subject of filmmakers: in the wake of François Porcile’s Le Paris de Doisneau (1973) and Poete et piéton (1981), he was the central character in a number of different films, including Sabine Azema’s Bonjour, Monsieur Doisneau (1992) and Doisneau des villes, Doisneau des champs (Doisneau of the City, Doisneau of the Fields) by Patrick Cazals (1993). But, of course, he devoted the majority of his later years to photography despite increasing fatigue, he photographed artists, singers and celebrities: Renaud Sechan, Sandrine Bonnaire, Jack Lang, Christian Lacroix, Isabelle Huppert, and the French group Les Rita Mitsouko -a whole new generation who clearly enjoyed their collaboration with Doisneau.

“Know where to be, without influencing the subject like wolves out hunting, move so as to isolate the subject cut it out of the herd I learned all that just by marking time.”

Things happened quickly at the end. In July 1993, while staying with friends in Dordogne, Doisneau had a heart attack. His wife, Pierrette, had remained behind in Paris and died in September. Hospitalized in Paris, Doisneau died on April 1st 1994. The couple are buried in the little village of Raizeux in the department of Yvelines, where they had met sixty years before. Doineau’s death was saluted by the press in France and abroad and he was unanimously hailed as the greatest member of the pantheon of humanist photographers. His legacy is a few seconds of eternity fixed on paper: a few seconds of wonder that afford us hours of joy as we discover ourselves and others in these pictures of “ordinary people in ordinary situations.”

His work survives him in the form of 450,000 negatives that over the course of a long life, he carefully filed and captioned. Today, his two daughters, Annette and Francine, have founded L’Atelier Doisneau, an organization based in the photographer’s own apartment and devoted to ensuring the posterity of his archives. In doing so, his daughters continue the course of their professional lives, since from the 1980s on, Annette had been deputy archivist of her father’s image collection while Francine worked with the Rapho agency on publications and exhibitions. The two of them ensure the diffusion and survival of this all but inexhaustible corpus. And very successful they have been: since 1994, exhibitions and publication of Doisneau’s work have constantly been center stage on the photographic scene. After the major Parisian exhibitions at the Musée Carnavalet and the Hotel de Ville came those in Dusseldorf (1997), Bogota (2003), Japan (2009, 201), Milan (2013) and many other international and regional museums. Retrospective or thematic. these exhibitions were very successful in making available to a new audience these instants full of tenderness and love, these characters as moving as they are amusing, these environnement epitomized in the photographer’s penetrating gaze. To these successes must be added others in the publishing world, since the last decade has seen a vast number of publications on various scales. They include Travailleurs (Workers; 2003), Paris Doisneau (2005), Portraits d’artistes (Portraits of Artists; 2oo8), and Palm Springs 1960 (2010); the entire universe of this modest collector of the instant is available to the great visual delight of a vast audience.

Light years away from the predators of current-affairs photography for over six decades Doisneau was the gentle fisherman in calm waters, “feeling his way … under the impulse of attraction and repulsion, driven here and there by events, allowing intuition to guide his hand.” It was a life during which this man with his clear, mischievous gaze and winning smile tells us. “I never noticed time passing, being too busy with the permanent, gratuitous spectacle afforded by my contemporaries and occasionally consoling them, when the opportunity arose, with a fleeting image. Over these decades. Doisneau tirelessly told us stories full of feeling, poetry; and humor, enchanting us with his capacity to transmit the fleeting but implicit tenderness that connected him with those whom he photographed. “The world that I attempted to show was a world in which I would have felt at home, where people were likeable, where I would encounter the tenderness with which I myself should like to be treated. My photos were a kind of proof that this world can exist.”

His special interest in the working-class milieu and its physical environment allowed him to make images imbued with a kind of social realism that also profoundly marked the literature and cinema of the time. Out of the

myriad moments, largely devoid of event, that he harvested during his random wanderings through the streets were born thousands of images which, on closer examination, reveal a wealth of inspiration and emotion that quite transcends the simple humanist definition with which this poet of the image is frequently identified.

When we go beyond a superficial reading, his work comes to seem infinitely more complex than it at first appeared. True, humor is, as we have seen, one of its essential components and is found in all its variants: ironic, tender and disturbing. In Doisneau, humor is an ingredient made up of refinement and restraint: “Humor is both mask and discretion, the shelter behind which one can hide: suggesting something with a light and playful touch, apparently without criticism – but the thing is said all the same.”

We cannot help but acknowledge that, behind this protective mask, Doisneau’s images are sometimes exceedingly somber. This is something that appears even in his very earliest photographs: the gas lamp, the paling fence, and even the interior are all bathed in an atmosphere of suburban grisaille and loneliness. This gravity is the more evident in another spectrum of Doisneau’s ·work. one that has been less widely noticed and published though it occupied much of his life, as we have seen: the images that he devoted to the world of work.

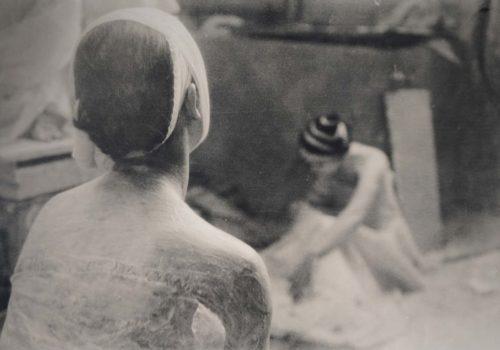

It began in the Renault factories in 1934 and continued to preoccupy him throughout his life. He illustrated working-class life with precision and no trace of voyeurism; at once present and absent, he was able to maintain a certain distance and, in this way avoid the trap of militant photography while at the same time focusing our attention with great simplicity on the work of the miners, steelworkers, dockers, agricultural workers, and sewermen. His profound empathy and solidarity with this world transpire as much in his selection of the infernal conditions of certain factories as in his portraits of workers, in which fatalism, serenity, and nobility are inscribed on the faces of men seemingly hardened by their tough professions. With an acute sense of light that he had learned at Andre Vigneau’s, a sense of space and the environment, Doisneau excelled at creating vivid portraits of men and women in the factory and the workshop. Here, the osmosis between photographer and model is self-evident. Doisneau persisted in this sociological enterprise over several decades with obvious sensitivity and commitment. This work was close to his heart and later inspired some regrets: “In fact, I took the easy way out. Picking flowers is much nicer than trying to make pastry out of clinker. I showed a lack of conviction and willpower – and I would have needed plenty of “ill power to break down the barriers behind which the living conditions of workers are concealed. I mean: everyone works or almost everyone. But I am thinking of the ones who do the sweaty jobs those close to the furnace or those at the coalface, all those inhabited by their pride at doing dangerous work.”

Nevertheless, this astonishing account of a world, many elements of which have all but disappeared from France – miners, steelworkers, and textile workers- is a veritable treasure for the archivist, historian, and sociologist. And it bears witness to the admirable fraternity of a man who, over four decades, from 1934 to 1975, was able to immerse himself in the daily activity of those who labor for their lives and to make of his images a paean of praise.

With his impeccable eye, overt humor and generosity of heart. Doisneau has, over the years, gleaned and harvested a bouquet of moments, encounters, and environments and made of them his own personal world: “The only people I photograph well are those who resemble me.” He lived to see the transformation of the suburbs, which have now “become a stultifying backdrop where fun is outlawed.He has always been solitary, many people never experience that vertiginous sens of solitude. But I have no difficulty with it because I see very early at moment like that.” This was the luxury that allowed him to traverse again and again his chosen quartiers between Paris, Montrouge, and Gentilly, shooting with a real sense of responsibility and with the previous consent of the subject. “One of the great joys of my career has been to meet and speak to people that I don’t know. Often, these simple people turn out to be delicious characters who create a poetic climate. One should only ever take photographs when overflowing with generosity for others … “

His sense of mischief and complicity connected him with his models and help to explain certain of his carefully staged compositions – works at which some have, in the wake of The Hotel de Ville Kiss affair, feigned astonishment. This objection seems completely fruitless since Doisneau has never denied setting up certain photographs. Examples include those in which his concierge and assistant, Paul Barabé, appears; he showed a remarkable ability to meet all Doisneau’s requirements. Another is the photograph Black and White Coffee, in which, he says, “they are not real newly-weds, they were extras from the Joinville studio. I asked them if they were happy for me to take a photograph, and yes, they were, then up pop this coalman. Of course, the black on white is a bit crude … ”

Pure luck! Another example was The Hotel de Ville Kiss, which embittered his later years because of the idiotic case brought against him in 1993 (forty-three years later) by a couple who thought they were represented in this image and were, of course, claiming financial compensation. Yet this very image formed part of a series of photos commissioned by Life in 1950 to illustrate the theme of Parisian lovers. Doisneau had never concealed the fact that these photographs were staged with two actors, who were duly recompensed at the time and were, moreover, genuinely in love. Doisneau was deeply shocked by the reaction of certain people to this court case, which continued after his death. But such images account for a very small part of the mass of photographs made by him in his guise as a “private reporter.” And their participants do no more than deliberately tread the boards of the little theater set up by the photographer. They do this, moreover, in the same way as all those anonymous characters who crossed his path throughout his life and left him one hundredth of a second of their existence. ”I always feel I must speak to the people that I photograph. either apologizing afterwards or asking permission in advance.” “The special attribute of the photographer must be the hope that a miracle will occur against all the odds. A kind of faith in fortune’s smile. Anything can happen on the corner of the street. I set my backdrop, a rectangle of space, and wait for the actors to come and play out I know not what.” ” Doisneau never imposed on anybody; he only

ever made suggestions. “The photographs that interest me, the ones · I find successful, are those that reach no conclusion; they never tell a story right to the end, they leave things open so that people can keep company with the image a while and continue it as they see fit: a sort of stepping-stone for dream, in other words.”

In short, they invite spectators to take part and make their own entrance on the stage of this timeless theater of the moment.

An extremly multifarious photographer, Robert Doisneau told the story of his era with a benevolence that cannot mask either his deeply reflective nature or the complete independence of his gaze. The field of observation that he established over several decades is very broad and covers the poor of this world, the forgotten, the lonely, the workers, the well-off, the artists, the dropouts, the dreamers, alongside the many others that fill the boxes of prints

in his studio.

It was a much broader field of investigation than is customarily acknowledged; he is, ironnically, confined too a hackneyed image of himself. In fact. it was the public and the publishers who, throughout his life focused on the more light-hearted and picturesque preferring them to others undeniably more sombre but also deeply endearing. honest and truthful. No doubt the images of Paris and its suburbs. in which some people effect to recognize

their own selves spicing up the image with a grain of personal nostalgia, are more immediately appealing. But nostalgia has, no place in the photographs of a man so much in love with life and too much devoted to the present to indulge in any such thing.

Throughout his long life, Doisneau cast his lines from the banks of the Parisian suburbs. This was his conclusion: “The population of Paris, rubbing up a against the urban structure, has given the city a kind of burnish that is very likable. In my endless peregrinations, I have myslef done so much polishing of the street ornaments that, for the first time in my life. I feel a vague sense of ownership. I should nevertheless like to take up a position relatiwly unknown to the free-market landlord and leave my door wide open to you. Let us take advantage of this generous invitation to visit and rediscover in his company a vast reservoir of precious instants, amorous gazes, permanent street-theater, and authentic characters accumulated over half a century of wonder-filled contemplation.