Photo London will open next week. Michael Diemar published in the latest issue of his magazine, THE CLASSIC, the following article written by Mary Pelletier.

“Keep looking – you just started!” This was a directive that I would hear more than once during the day I spent looking at photographs with dealer and collector Robert Hershkowitz. The occasion? I had travelled down to West Sussex to see the selection of photographs chosen for his upcoming exhibition at Photo London: The Magic Art of French Calotype. Paper Negative Photography 1846–1860. On a blustery winter’s day, I found myself in his barn in the countryside, surrounded by the greatest names in French photography history.

On one side of the room, a Charles Nègre photograph from 1851 was propped against a wall. The portrait of a street vendor bedecked with bells was paired with its original paper negative, the ghostly figure outshone by decidedly modern blocks of cream and brown. Another frame housed a print by Gustave Le Gray and Auguste Mestral, who would occasionally join forces while working on their Missions Héliographiques assignments. For this collaboration, their subject was the looming Saint-Front Cathedral at Périgueux, set against a crystal clear sky. (The negative, which is held by the Musée d’Orsay, shows the jet black tones used to achieve such a pristine positive atmosphere.) Directly in front of me, a print by André Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri. A general view of a French country estate revealed six, then seven, then nine, people within it. “Keep looking!” Hershkowitz urged. We landed on thirteen figures in the end.

“Early photography takes patience, time and commitment,” he told me. “I love to share, and when I show people photographs, I always learn things that I haven’t even seen.” Below, he explains his motivation for bringing early French photography to a British audience at this year’s edition of Photo London.

You featured in the very first issue of The Classic, speaking about the Roger Fenton exhibition you curated for Photo London 2018. Now, you’re working on a new exhibition for the fair. What’s the focus this time?

For this edition of Photo London, I’m curating a show I’ve titled The Magic Art of French Calotype: Paper Negative Photography 1846–1860. The whole point of this exhibition is that early French photography is totally new to an English audience. French calotype photography is almost non-existent in British institutions, with perhaps a few dozen examples buried among many thousands of British ones. And these are never exhibited. How would the art-going public respond if there were zero awareness of Manet, Courbet, Delacroix, Ingres, Corot, Millet, etc., and then it suddenly experienced a major exhibition of mid-19th-century French painting? It would have a serious impact on the art-going public. This is what I’m hoping for – I’m proselytising! I want to introduce this material that I love to the British art-going public who may not have any awareness of it.

The Magic Art of French Calotype takes its name from a landmark publication in the history of photography – can you tell me about the influence of the work of André Jammes and Eugenia Parry Janis?

The title of the exhibition is an homage to André Jammes and Eugenia Parry Janis’ 1983 book, The Art of French Calotype. When the pursuit and acquisition of fine photographs became the common passion of a very mixed group of the most art-savvy individuals and American and Canadian institutions in the late 1970s, early French paper negative photography was considered the most desirable. This feel- ing was solidified with The Art of French Calotype. Something I took away most from the book was Eugenia’s feeling, her love of the material. She’s a historian, but you can feel the love of what she is writing about, and this is very rare for an art historian. For this exhibition, I’ve added another word to the title: magic.

Where did the word magic come from?

In 1851, Francis Wey said, “Photography has attained the magic feeling that neither painting or drawing could have reached.” Photography hovers between concrete reality and the stuff dreams are made of. Magic. The concept that “Photography can teach the mind to see” was a commonly held conviction among the first generation of photographers. Magic. Photographic prints can be extraordinarily beautiful. Magic. There’s a way that photography can dematerialise the thing it is looking at. And that’s one of the underlying roots of the magic. But there are a lot of things that can be part of the magic – an image can be hard or soft, it can have a range of subject matter, the way things are framed – you can go on and on about the individual things that make a photograph special, but when you put it all together in one image, it’s magic with capital letters.

When did you come up with the concept of doing this exhibition?

It came to me slowly. I probably started seriously thinking about it six or seven years ago. I thought of one or two possible venues, but nothing worked out – and time is growing short at my age! So when we were able to put the Fenton show on with Photo London within a year of first thinking about it, and that was a success, it made another exhibition with Candlestar and Photo London an obvious choice. They’ve been fantastic to work with.

How did you go about planning for a large survey show, in terms of getting the material? How much of it is from your own collection?

It comes primarily from French auctions, or from French dealers. Most of the photographs belong to me – some I’ve had for a long time, and others are more recent acquisitions. A few pictures I own with others, and I’m borrowing a few as well. Over the years, many of the French dealers and specialists have become great colleagues and friends, including Serge Kakou, Bruno Tartarin, and Serge Plantureux. Early on, the auction house Beaussant Lefèvre sold a lot of early material. Marc Pagneux was an incredible dealer and a great source, and he used to do the auctions at Galerie de Chartres. More recently, I’ve been sourcing from Christophe Goeury at Millon, Antoine Romand at Ader, and Austin Farahar at Chiswick Auctions.

Photo London tends to tilt towards the modern and contemporary, when it comes to the work on show; both you and Hans Kraus have brought 19th-cen- tury work to Somerset House in years past, both on the stands and in the public exhibition space. Why is it important to bring this material to the fore at a very contemporary-focused fair?

Multiple visitors in years past said our booth was an oasis, so different, so interesting, so beautiful. Far and away best of show! This year in our booth, and in the French exhibition, we have perhaps our last opportunity to reach a British audience with great early European photography. Our booth, curated and organised by Paula, my wife and co-director, will feature early British photographs including images by Backhouse, Talbot, Hill & Adamson, Howlett, and Cameron.

I have been advised that the planned exhibition has too many pictures for purpose as an introduction – but I’m still adding pictures at the last minute!

I am betting the absolute novice will discover at least ten meaningful moments, and the experienced eye a nuanced feast. But each novice will see a different ten. Careful, slow looking will reveal subtle differences in colour, varieties of fineness in registration of detail, and the kind of things that connoisseurs delight in. I have a motto for the show, and it is love of looking, joy of seeing.

What are some of the photographs that you knew you had to include?

I had to have print-negative pairs. They are like pieces of the true cross, to use a weighty simile, and act as the backbone of the exhibition. Nothing explains or completes the early photographic experience more than seeing these pairs. This exhibition has nine pairs; there was a big show of French calotypes, Primitifs de la photographie, at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in 2010 and they had 12 pairs. Negatives were also exhibited individually without the prints. Eugenia Janis noted, “great beauty was ascribed to the negative itself,” with its independent aesthetic, darkly luminous and mysterious. Here we have negatives by Humbert de Molard, Robert, and de Beaucorps. The process by which a paper negative is transformed into a positive print is the fundamental magic of photography.

The negative itself can be beautiful; the print can also be beautiful. But how one becomes the other – that whole relationship is magic.

Can you tell me about why you’ve chosen some of these pictures?

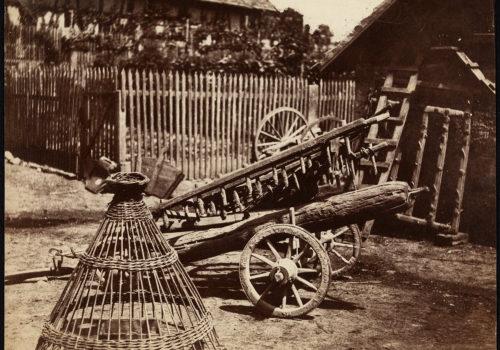

Now: look at the Dijon! The absolute star and one of the starting points of the exhibition. A gorgeous print of an entertaining, complex image. The motif of “wood-space-wood” objects – cart wheels, ladders, fencing, a large agricultural implement and fowl cage – is repeated in about twelve different instances. The image is a decidedly constructivist treatment of an agrarian situation. I have lived with it for more than forty years and never tire of revisiting it.

I love it when people tell me things about my photographs that I’ve never seen. For years, I thought this Baldus was from a glass negative. Then a collector said to me, “Look at this edge.” It’s from a paper negative! Taken in 1855, it is a detail of the Chateau St Cloud, later destroyed in 1871. It feels like a giant Atget. The print is untrimmed; you can read the whole negative, which extends beyond the image itself. Amazingly rare.

You tend to read photographs as though the parts of them are passages. You might read just this area, and then move to another area, and see how the image changes between passages, how shapes and tones relate to each other, and how one passage is contained within another. Because photographs are small, you can do it all in your hands, before you. You can’t do that with big paintings; there’s an intimacy with photography.

Who are some of the other key figures in the show?

Humbert de Molard is certainly one of the key fig- ures. I have two print negative combinations of his, he’s very early. Henri Le Secq is another, and so is Gustave de Beaucorps. I’ve included on of the very first purely archaeological photographers, Eugene Piot, who intended his salt prints to look like litho- graphs. Reproduced in 2012 in the catalogue for the “Le Gray and Modernism” exhibition at the Petit Palais, this print of a Greek temple near Naples is minimalist, one rectangle atop another. His print of a temple on the Acropolis – clean hard lines, high contrast – suggests a Bauhaus print.

One of my favourites in the show is a view from Chartres by Charles Nègre. It’s one of the sculptures of the saints. The rooftops in the low left-hand corner indicate just how high Nègre was when he made this picture – he was at an incredibly high vantage point to make this image. All of the Nègres in the exhibition came from Jammes, greatest of the French collectors/dealers.

So there will be a lot to see!

Some of these photographs are so rare that even people with photographic knowledge won’t have heard of some of the photographers in the show. We have a picture signed “Pablo” of a ruined French basilica. This is the nickname of French photographer Paul Emile Mares. We have another photograph of his from Algeria, from 1855. It’s the kind of image that would not be made by a painter; the situation would not attract a painter’s attention.

As I said before, this show is for both the connoisseur and the beginner. That’s absolutely important – that there is something everyone can learn from, no matter what their experience in photography history. I’m happy to have anonymous photographs in it, for that reason.

In addition to the print-negative pairs, what are some of the other elements that have gone into the selection?

Many of the photographs chosen induce revery. They are dreamlike. There was a show of early photography at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called The Waking Dream, which I think about looking at these – their dreamlike quality. In this Giroux, for example, the control and the registration of detail can’t get better than this. There is an incredible delicacy in the transitions between areas of light and shadow. Giroux has been one of my favourites for years.

I have also included prints where a subject is very decontextualised; pictures where the background of the subject is not indicated. There is a Le Secq of a plaster cast of a head of a sculpture; another one is a Salzmann print and negative pair – a sculpture of an angel that looks as though it is levitating; the third is an anonymous Romanesque capital, and you cannot see anything that might be supporting it.

Having worked for many years with both British and French early work, what are some of the major differences you see in the motivations of those early photographers on both sides of the channel?

I have trouble putting myself in the photographers’ shoes, knowing exactly why they made the particular pictures they did. But there is a British sensibility and a French sensibility in the early years. You can find there is certain subject matter that appears in French photography that does not appear in British. You can find street scenes with people much more in French photography; Fenton is the only British photographer to place people in street scenes.

There are farmyard scenes in French photography, as you’ll find with Le Secq, Dijon, and Giroux. Surprisingly, you don’t find the same kind of images in British paper negative photography. You can sense a difference in the way they approached a subject. If a British photographer and a French photographer made an archaeological picture, the French photographer would be closer to the subject than the British photographer. This is a repeated phenome- non. They seemed to have different ways of seeing.

Do you have any thoughts on the state of connoisseurship in the field?

A photograph is both a physical object and an image; it is on the interface between these two aspects that the sometimes cryptic heart of the photograph can be discovered. Seeing a French photograph for the first time, my initial response is to its physical properties: overall condition, size of print (is it trimmed or cropped?), colour in general, colour in highlights, negative type (paper or glass), print type (salt, albumen, carbon, ink), coating (albumen, wax, heavy or light varnish). I used to flatter myself thirty years ago that I could date a print within two years by simple visual inspection.

As for the image side of the equation, I consider motifs and their distribution, the (ostensible) subject, structure of light, compositional features, making special note of anything idiosyncratic. The most rewarding moments come from connecting the right name to a photograph, whose identity has eluded curators and scholars, based on intuition fed by experience. I think that the time of the connoisseur is over. The collective experience of sorting through piles at auctions and dozens of photographs with dealers, making judgments of value at every step will never be seen again. The uniformity of prints in uniform editions mitigates against connoisseurship, as do weightless, disembodied images on the screen.

How have you seen the collectors of 19th-century photography evolve during your time as a dealer? How have tastes changed?

Collectors and institutions change. I think that, after that first rush in the late ’70s and early ’80s, American institutions bought a lot of early photography. And then something happened with the culture – things changed, and the internet took a bigger and bigger hold on people’s lives. Early photography got a bit lost in the shuffle. It takes so much time to get everything out of a photograph, and people don’t have that time today. People have less of a capacity to sit and think with something for a long time. But that’s one of my favourite things to do.

In a few years, in 2039, it will be the 200th anniversary of the birth of photography. And I think that that might the point at which people begin seriously revisiting this early material.

Are you considering retirement after nearly 50 years of dealing?

I’m getting on in years, and my daughter Kate is beginning to work with me. After working with charities for years, she wants to get involved and is starting her own business selling material. She’s also creating a website for us, which we’ve never had. I’m probably the only dealer in the world without a web- site! In terms of retirement – I was going to retire when my first grandchild was born – she’s now 11. I just can’t let go! It’s too important to me. It keeps me going. And I am still finding new things I love! It doesn’t stop. I should show you a few other things that I bought in November in Paris…

Text and Interview by Mary Pelletier

The Magic Art of French Calotype.

Paper Negative Photography 1846–1860.

15-19 May 2024

Photo London Somerset House

London WC2R 1LA

www.photolondon.org

Article first published in THE CLASSIC Issue 11.

The magazine is available to download at :

https://theclassicphotomag.com/