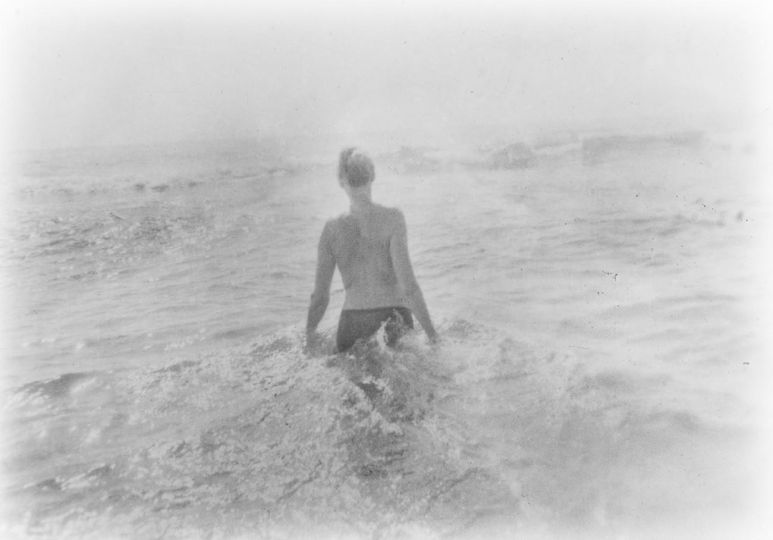

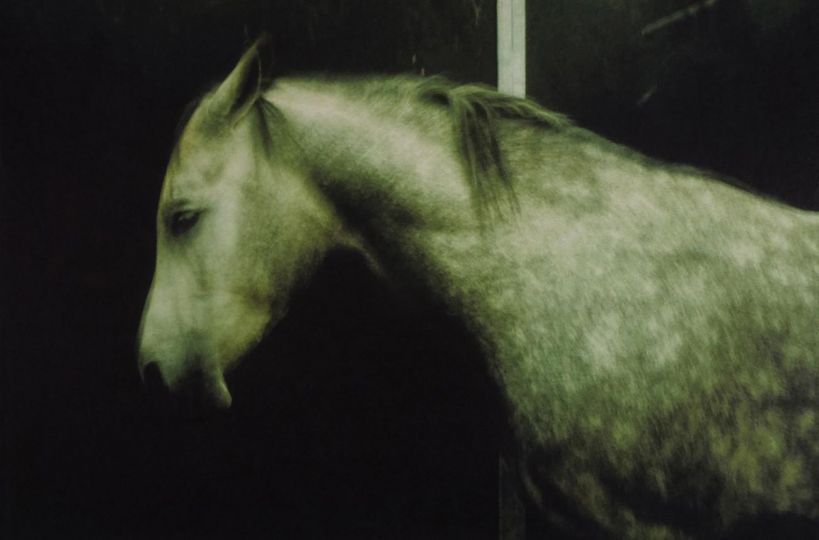

But who is Paul Senn? With his sharp eye, he will witness for two decades, from 1930 to 1950, a tragic era during which will be put in place fascism and Nazism, then a post-war from which he will draw glimmers of hope. This off the road Swiss photographer will devote his short career to his country’s press magazine. He is not a war reporter but rather a “humanitarian reporter”, especially a humanist photographer. He is known in Switzerland but absolutely not in France and even less in Spain.

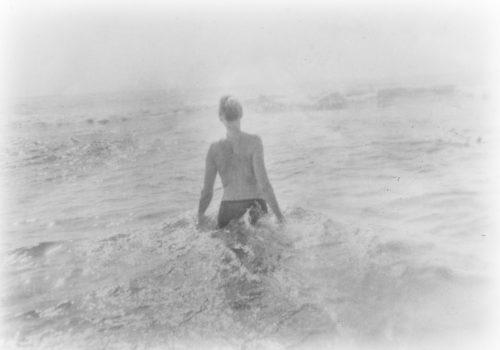

In the 1930s, against the backdrop of economic crisis, social clashes and political violence, Swiss photographers, most notably Paul Senn, reported on the news, Rolleiflex and Leica in hand, for a very dynamic illustrated press. . This is the golden age of photojournalism in Europe and Switzerland is taking its place. We are far from the cliched image of winter sports and majestic lakes, chocolate and cheese wheels. Paul Senn, early in his career, empathically photographed workers in the fields or factory, but also a workers demonstration in Geneva in November 1932. Repressed by the army, it degenerated into a bloodbath: 13 dead and 65 injured. His reportages on abandoned children, placed in homes or with peasants and living in unworthy conditions, create a scandal.

He travels through Europe, already with a predilection for Spain where he goes several times before the outbreak of the civil war. Tireless support for the victims of war and Spanish exile, he will return under the bombs in 1937, alongside his friends of Ayuda Suiza, an unknown organization whose history foreshadows modern humanitarianism. He will also witness the exodus of the French army to Switzerland in June 1940, a little known episode. From 1945, he will also track the joy of Liberation and reconstruction around the world. In France, Italy and many in the Americas, he will travel extensively from Canada to Mexico, focusing on the United States whose dynamism and colors will fascinate him.

The reports that are the subject of the exhibition at the Memorial of Camp of Rivesaltes and found in the catalog, on the Retirada in the winter of 1939 and his extraordinarily moving work on internment camps under the regime of Vichy in 1942, allow to discover an important reporter for the history of photojournalism but also for the history of Spain. We can compare Paul Senn to David Seymour-Chim, for his way of photographing children and the very particular framing of the 6X6 that he masters perfectly, to Roger Schall, for his sophisticated technique and the variety of topics he deals with in the press magazine. One could even speak of a “Swiss Capa” in the sense that he practices what Robert Capa’s brother described as “concerned photography”, generally translated into French as “photographie engagé”. Like Capa, he published in the illustrated press of his country reports with social connotation. Like Capa – or David Seymour-Chim – he worked at the heart of the Spanish tragedy with support organizations whose photos were used to raise funds.

Like Capa, he provided photos and texts to newspapers. In the special issue of Zürcher Illustrierte, June 18, 1937, in the middle of the double pages occupied by Paul Senn’s reports, ZI also published a double page of photos of Robert Capa. Did Paul Senn meet Robert Capa at the French border? There are more than a hundred journalists and photographers in Perthus on January 28, 1939, but Capa, like Chim, are not in that particular spot that day. They could have met in the following days.

While preparing an article for Le Monde on the inauguration of the Camp of Rivesaltes Memorial I first met Paul Senn, it was in 2015. To illustrate the dossier, the iconographer of the newspaper showed me a site on the computer presenting the photographs of a certain Paul Senn, a Swiss who stayed at the Rivesaltes camp in early 1942 to make a reportage for the Swiss press. To go further, I went to see the archives of Paul Senn kept in Berne. Like all the treasures in Switzerland, these archives are installed in an antiatomic shelter, that of the Museum of Fine Arts. It is accessed by an elevator. Two floors down, behind a huge armored door, sealed in gray archive boxes are sleeping tens of thousands of negatives. Over the decades, several teams of archivists have tried to put order in this work. For twenty years, Markus Schürpf has been managing the photoCH site (https://fr.foto-ch.ch/#/home), a huge database that lists the work of Swiss photographers. He integrated the images of Paul Senn and has organized several important exhibitions in Switzerland on this photographer.

I thought back to these very strong and moving photos by reading the testimony of Friedel Bohny-Reiter, a Swiss nurse present in Rivesaltes between November 1941 and November 1942. This text was discovered by a Swiss historian, Michèle Fleury-Seemuller, and published under the title Le Journal de Rivesaltes 1941-1942. With simple words and implacable sentences, Friedel describes the daily life of the camp, the misery and fear of the future, the all times cold, the wind that slaps, the hunger pangs, and especially the thousand and one tricks to prevent the deportation of Jewish children, including hiding the action from the Red Cross authorities who advocate “strict neutrality”. Reading her modest daily accounts, we feel what she has experienced as if we were in the camp. Paul Senn’s images give exactly the same sensation, they send shivers down your spine, literally. This recovered testimony and these rediscovered photos bring to the memorial of Rivesaltes, concrete monolith of Rudi Ricciotti, flesh and blood. The words of Friedel Bohny-Reiter and the photos of Paul Senn testify forever for all children imprisoned, hungry, abused, murdered, yesterday, today and tomorrow.

Michel Lefebvre

Paul Senn

Until November 3

Rivesaltes Memorial

Christian Bourquin Avenue

66 600 Salses the Castle

http://www.memorialcamprivesaltes.eu/

The catalogue of the exhibition is published by the éditions Tohu Bohu.