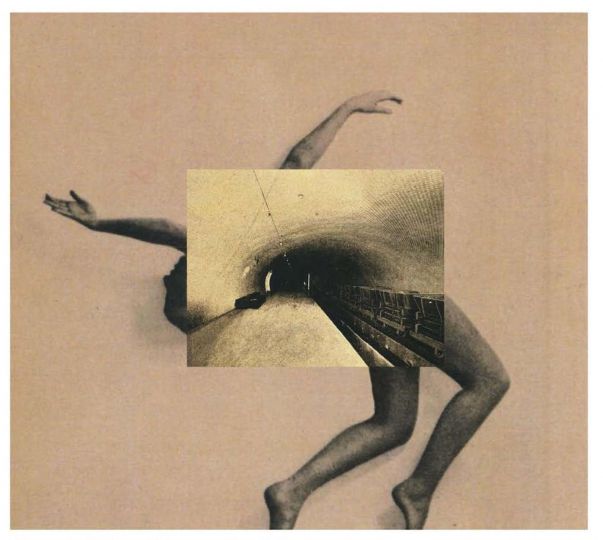

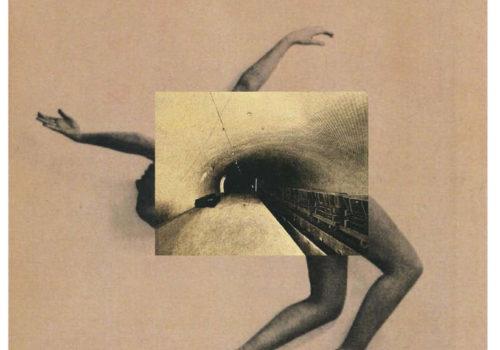

Olivier Beytout is particularly fond of the word “Cyclops.” “I think every photographer,” he explained, “is a Cyclops, since, if you’re using traditional cameras, you always keep one eye closed and show only the oversize, round eye of the lens.” Olivier Beytout is all smile, but his kindness does not cloud his lucidity. Olivier Beytout is all eyes, generously gazing at the world—the world of beings and thoughts, rather than the world of things and riches. Age suits him well, giving his profile a Roman look, serene and calm.

He loves talking, or rather debating, since his ideas glow white hot, just like the sun, or red like metal that is being purified and refined. But he doesn’t like discussing photography so much, since it is “a science that has attracted the greatest intellects, an art that excites the most astute minds—and one that can be practiced by any imbecile,” he warns from the start, quoting Félix Nadar.

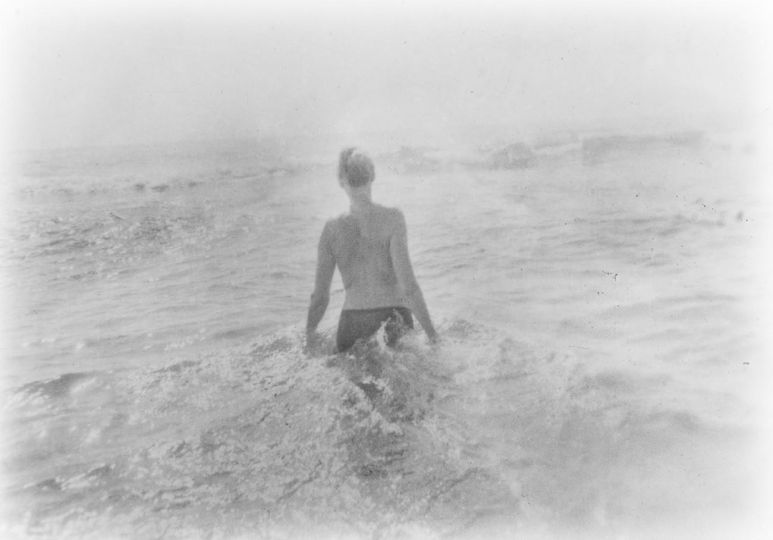

He would rather talk about anything else: society, with its dreams and blind spots; politics, with its utopias and lies; culture, with its sophistication and its smoke and mirrors. But above all, he likes to discuss humans, that species that brings all together at a certain time, no matter what part of the world we call home. The photographs of this admirer of George Orwell and his 1984 are overflowing with this truth, the way a wellspring overflows, or a fountain, or a human heart. These photographs await you patiently, allowing you to take your time: the viewer is the final character of an image.

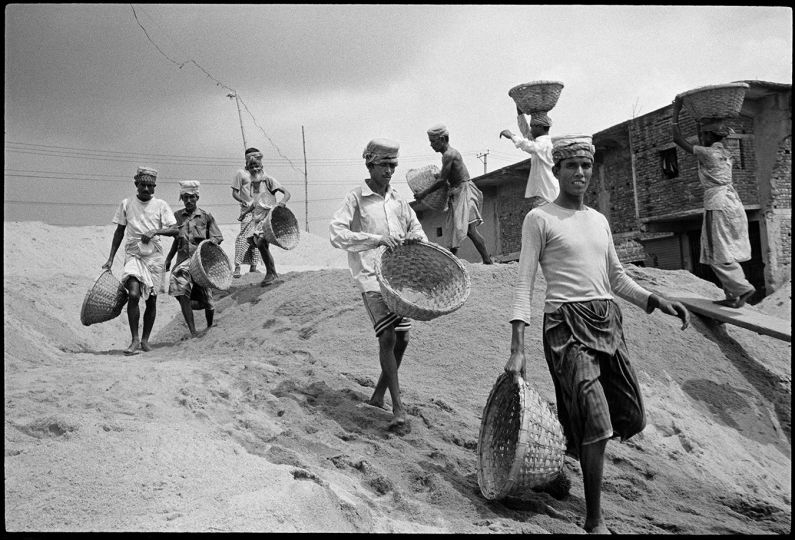

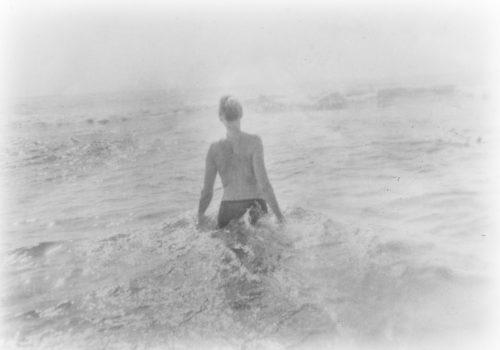

In the Eye of a Cyclops, Beytout’s latest book, is a well-appointed little publication that brings together just 108 of his photos in chronological order, according to his own design. “I react against the current trend to blur the lines, fudge things up, without showing anything. If a subject gets on my nerves, the photo gets on my nerves. I couldn’t care less about fashion, its geniuses, its empty constructs.” Like his revered filmmakers, the Eisenstein of Ivan the Terrible, the Bergman of Shame, the Antonioni of L’Avventura and The Red Desert, and all of Fellini and Buster Keaton, the great photographers from his personal pantheon are saying something and are not vain: “Clearly, Henri Cartier-Bresson because in his photos there is more than he shows; Sebastião Salgado, when he makes his superb photographs of people, migrants, miners; Joseph Koudelka, and many others, sometimes unknown. The function of art, in general, is to bring to light what is hidden. Aestheticism may be a means of expression, but not the goal. Among Americans, I admire Dorothea Lange who has written wonderful things about her work, without embellishing the obstacles, the tedium, the repetitiveness, day after day, until she arrives at a form of miracle.” A task, a goal, an effort, an idea, an image.

As Lange aptly put it, “one doesn’t photograph people one doesn’t know just for fun.” Olivier Beytout goes straight to the heart of the matter in expressing his convictions, using Félix Nadar of 1857 as a reference. “You can grasp his theory of photography in an hour; it might take you a day to learn the practical basics. But I will tell you what can’t be taught: a sense of light, an artistic appreciation for the effects produced by different days and in combination, the application of such and such effects depending on the nature of the face that you are going to capture. What can be taught even less is moral intelligence about your subject, the rapid tact that establishes a rapport with your model, that allows you to assess a person and guide him or her in their habits, in their ideas, depending on their character, and enables to you create (not in a banal or random way, a bland visual reproduction within reach of the least lab assistant) the most familiar and the most favorable likeness—an intimate likeness. This is the psychological side of photography, and I don’t think the term is too ambitious.”

Olivier Beytout doesn’t put much stock in great flights of theory or technique. Over forty years of photographing, he has used only three types of cameras: “a Pentax, three Canons—one for black and white, another for color, and the third as a spare—and a Nikon.” Everything comes down to practice. His great contemporary hero is the British Don McCullin, “a wonderful photographer who took amazing shots in every situation he ever found himself in, from Vietnam to the streets of London populated by homeless people. All his work is sincere and direct, just like himself.”

There is nothing snobbish about this French gentleman who hates the Anglicisms, the approximations, and the dominant values of contemporary culture.

Valérie Duponchelle

Valérie Duponchelle is a journalist at Le Figaro.

Olivier Beytout, Dans l’œil du Cyclope

Published by Zellige Editions

€30

http://zellige.fr/