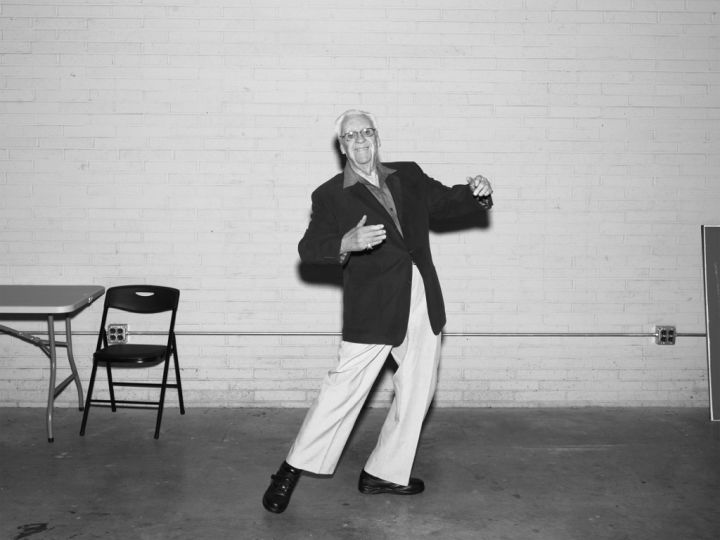

Jeff Whetstone’s photographs and films imagine rural America through lenses of anthropology and mythology. Whetstone’s work interrogates the stereotypes of rural people – ignorance, poverty, and self-destruction – and explores the complicated bond between people and the landscape. Whetstone’s photographs investigate the role gender, geography, and heritage play in defining the human position in the natural world. His last series is entitled Central Range.

Andrea Blanch: How do you approach your work?

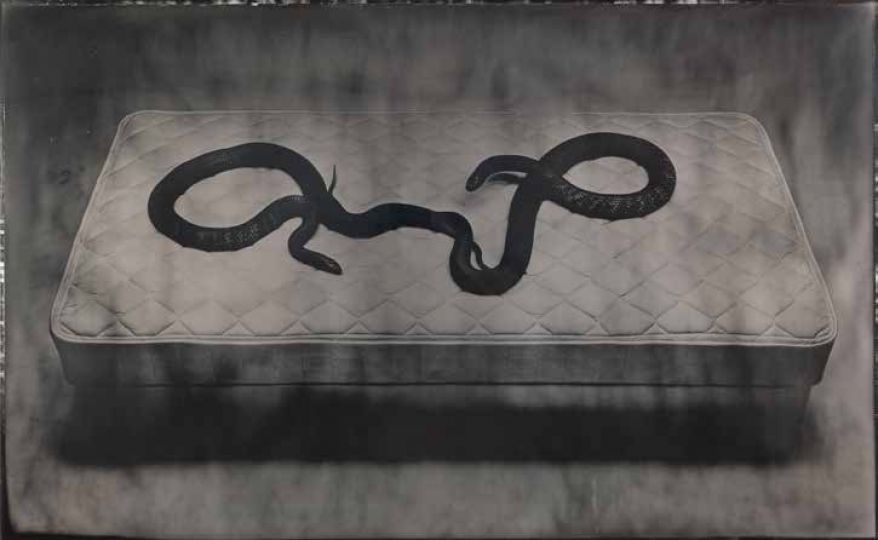

Jeff Whetstone: Personally, I thrive on chaos. I really like chaotic situations, and as a photographer part of my strategy is improvising around chaos. There’s a video of a snake I caught, Drawing E. Obsoleta, which is, in a way, me dealing with the very unpredictable nature of the snake and trying to control it, knowing that I can’t control it. Maybe as a species, our relationship to nature is trying to control something that is really not necessarily chaotic, but unpredictable. I think our frustration and our attraction to nature comes through that. It’s a bigger force than we are. The unpredictability of nature is something that I think we’re all trying to battle with.

Can we talk a little bit more about the images in Central Range? They’re very beautiful. How did you come by these structures? What is it that possessed you to shoot them?

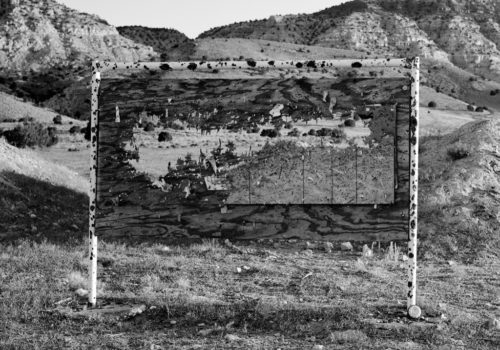

I came to those structures through a very chaotic approach. I spent two summers photographing locusts, or grasshopper swarms in Utah, Nevada. I was very interested in the history of the Rocky Mountain locusts, which were the largest conglomeration of terrestrial animals that the earth has ever witnessed. The locust swarm in 1847 really changed the history of the expansion west. After two years of photographing locusts and getting basically one usable picture out of it, I realized they’re not that impressive photographically. It’s very hard to record the imagery of a swarm of locusts and I decided I would never take another picture of a grasshopper again. I still had a month out in Utah, it was all paid for, I’d bought my ticket and made all these arrangements. I had a car full of cameras and film and I said “Well, what’s next?” I started driving and I drove to what are targets on target ranges. I was looking for something. I thought they were beautiful, and I photographed this one target, kind of over and over. I guess I realized that these targets are kind of ominous. Public parks in Utah are, in a way, billboards or vestiges from a really violent history. That violence, those wars out west in the middle of the 19th century, the landscape doesn’t record them. There were no buildings to record them; what records them is the culture; the gun culture of the west: the targets. You can see the vestiges of that expansion recorded in an abstract way through these targets. I thought they were, in a very confusing way, in a confused space. Hopefully maybe even confuse a sense of where it is, what it is and maybe even confuse historical eras.

Why is it called Seducing Birds, Snakes and Men?

The seducing part of that were the pictures. They were vehemently beautiful. They’re breathtaking, but once you realize what they are, they’re kind of violent. I mean, how many bullets went through that board? For what? Well, people playing with guns, and target practicing and hunters getting their targets out, but you know, lots and lots and lots of them. What I did, I was kind of playing a little bit with Utah. I went to every town named after one of the new apostles of the church and photographed their target range.

Is that what those are?

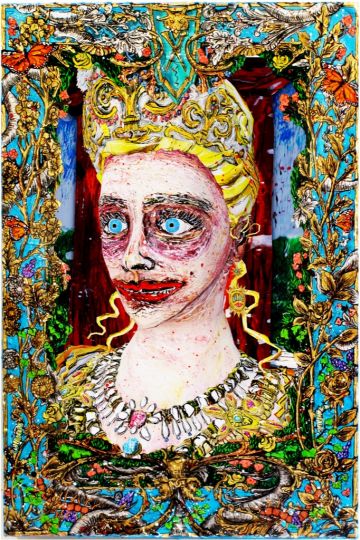

Yes, those are target ranges in all the towns named after the apostles. So, I was kind of playing with the violence of church history, not to pick on the church or any particular denomination, but that’s where I was. I was in a landscape slaughtered by territorial violence, and there were target ranges in every little town. They were beautiful. I must mention, Seducing Birds, Snakes and Men – That was the name of the show. Louise Bourgeois was asked “what is art?”. Art is seducing birds, snakes and men. She’s the coolest ever. I was so glad that show was about birds, snakes, and men. There was a little homoeroticism in the show too, so I thought it was really appropriate to use Bourgeois’ quote.

There were 6 images in that show, but what was homoerotic?

It’s in a video that was called On the Use of a Syrinx, it was about turkey hunting.

It was part of wild men, the guys in camouflage. How do you hunt turkey? You only shoot the male bird and the only way to get the male bird in the range of your gun is to imitate a female mating call. So we have male hunters, imitating a female bird’s mating call to attract a male. I put little tiny microphones on the hunters, and asked them to translate what they were saying to the male bird in English. In the end, it became sort of an x-rated hunting documentary. It’s kind of funny, it’s on the website and you can watch it. It’s funny and horrific, yet somehow kind of alluring and savage. We had this male in a very southern dialect talking as if he were a female describing what kind of sex he would have with that male turkey.

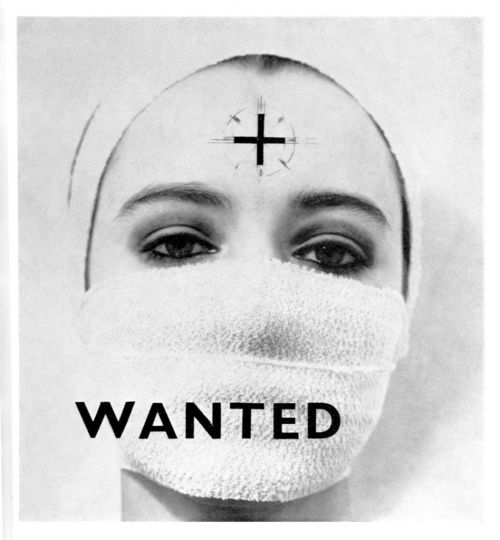

You have talked about Deliverance. When I think of Appalachia, that is the first thing that comes to mind. In your words, how did that influence you and your work?

Where I grew up was about 50 miles, as the crow flies, from the set of Deliverance. It came out when I was about 12 years old. It was a movie that kind of devastated Appalachian culture in ways a lot of other stereotypes didn’t. I think part of the reason it was so effective in really coining this Appalachian stereotype of these sexual predators out in the landscape, is that there was a great deal of truth within the movie. It was a movie about tourists against natives, about progress against nature, about is there anything to be saved of indigenous culture, about rural Appalachian culture against this cosmopolitan culture moving in. All these issues were very much alive in Deliverance. Deliverance is a fascinating book by James Dickey and film by John Boorman that investigated a lot of issues people from rural Appalachia were dealing with. Then there were sex scenes, specifically the rape scene. What it did for me as a kid, was that it made me afraid of my neighbors. All of a sudden I was like “man the Lawly boys that live up the road, I’m going to go down to the woods and get raped by them.” It made me scared of my own culture in a way. It’s a movie that was both very respected and very reviled. I grew up with these masculinity contests. Just like a lot of rural or urban boys, we had a lot of the southern masculinity contests and I was never a winner of these contests at all. I kind of saw things from the outside.

Deliverance has been a really important part off how I think, how others think about Appalachia. I really love to play with masculinity in my work. Sometimes I make it really sweet, sometimes I pose men in the flesh, and sometimes I make it really scary. But what I love about doing it is that the men and I work together on this. It’s not like I’m secretly manipulating them into a pose. I tell them exactly what I’m doing, tell them I’m playing with masculinity, the camouflage costumes, and we collaborate. I feel that’s really fun, more than fun. I guess everyone in a way thinks that the south is this monolithic, homophobic right wing Trump supporting area, which it’s not. It’s not at all. It’s very diverse, and the more you get into peoples’ personalities, everybody is post modern and a real mix of who they are, who they portray themselves to be and how they understand their own portrayal. I love having those conversations with people in rural regions.

You previously talked about how you have a cousin or an uncle that you said had a biological clock, he knew how to time the suckerfish?

That was my uncle Tim, his story has a huge influence in my life because of what this story illustrates. He caught these suckerfish that no one really eats except really traditional people in Appalachia. They’re actually incredibly delicious, but no one catches fish to eat them anymore, especially suckerfish. Well, he does, he loves them. I said, “I want you to take me suckerfishing so that I can photograph it,” and he said, “well, Jeff, when the first dark wood petal hits the ground, they’ll start running.” I thought that was so poetic, because it visualizes that middle of May when the first dark wood petals would swoon. Once they’re done blooming, the petals start following him. When the first one hits the ground, it releases a signal for a migration to happen. Because they’re migratory fish, they swim upstream like salmon spawn. That clock is so ancient, and so mystical. That mysticism of nature, it’s something that I think we lost. That now we look at nature through these scientific ecologies, and not through mystical ecologies where trees communicate with fish. My uncle Tim understands a lot of what the Appalachian people say: that old-fashioned wood talk. Literally a mystical, anti-modern way thinking about nature. I really want to hold onto that.

So what was your clock, what was your knowledge?

You know I grew up in a very rural area, no one lived near me. We lived on this defunked farm way out. I didn’t have any neighbors my age, so I was pretty much left to my devices. My entertainment was catching animals, watching animals, and hiding from animals. As a kid, I would enter the woods as an eleven year old with two dogs and a complete thought of fascination and fear. I was scared the whole time, I was constantly hiding and searching and catching things. If I heard the slightest noise, I would hide. You know, as a kid, fear is sort of fun, theres’ something exhilarating about fear. During those periods, I understood how animals, even something like salamanders, would return to the same little spot over and over. I got to know certain birds that would nest in the same trees, and the snakes that I would never catch were always in this rock pile at a certain time of day. I figured that there was this whole system of natural habits that seemed to be hidden to us humans. The secret of the hundred acres around our house. That’s what made me really go into the study of biology. I studied zoology, and realized that it was even broader than that, and I found that really fascinating.

You also say that you are a performer of sorts, and I was wondering if that is one of the reasons why you might chose to use an 8×10?

Yes, definitely. The 8×10 is my magic hat. I have to have some kind of weird contraption that never really wants to work right. My 8×10 is really beat up, it’s always giving me trouble, but it allows me to not hide behind the camera to observe someone. It requires me to enlist the help of someone in the making of their image. Someone will ask me “can I help you with that thing?”, and I’m like “actually you can, can you hold this for a second while I put this screw in?” No matter what type of photographer you are, a sports photographer, a nature photographer, etc, someone will come up and ask you about your camera. It became a joke and I really embrace that. With an 8×10 the question, “why do you use a camera like that?” become a normality. When I get that question, I can give a short talk about the history of photography. The history of the field is fascinating and I think other people find it fascinating as well. That’s why they want to know why this camera. I want to try connect to all the people who’ve used cameras in the past. There’s something magical in the making of film, what makes it different. What really makes it different to me is that I have a conversation and enroll people into my endeavor. I am the performer, I think that’s what a lot of people don’t understand about photography. The performer behind the camera is really intense and interesting, and sometimes a lot more interesting than the performer in front of the camera.

So you are the head of photography at Princeton – if I was to enroll in your course: what would I be learning?

That’s a very good question. It may surprise you that you learn about art history, especially history about Renaissance paintings. A lot of art is based on representational image culture, especially in photography. If we talk about light in photography, you can take Hollywood light all the way back to Caravaggio, or even before – Raphael. You learn about Raphael and Caravaggio and that kind of western art history. That made the birth of photography imminent. Photography had to be born after Caravaggio painted those paintings. Because if we’re advancing our language in art and everything else, photography is the next step. The first day of class, I take my students to the museum and we look at paintings. We look at Diane Arbus and talk about what modernism means. So, you learn that, and you try to unlearn things too. Everyone knows how to take a picture, but you don’t have to know how to take a picture to take a picture. Everyone is almost a natural at it, but what are the decisions that you are making with your phone when you frame something? I don’t think anyone thinks about that consciously. I try to go into vernacular photography too, and try to talk about the myriad of decisions and hopefully I turn people onto art. That’s the main goal for me: turn people on to a lifelong passionate love affair with art. Humans have made art before we were humans. When we were homoerectus or neanderthals, we were making art. Art is older than homosapians, the thing that connects us to our evolutionary routes more than anything else, maybe sex, but art and sex are the first two professions, I think art was first. How else are you going to get a mate, you make something. Or you make him something, you do a dance or you sing a song – it’s art that makes us love each other.

Photography is the gateway drug. Everyone loves photography, if you learn a lot about photography it doesn’t take very long. You’re quite close to the steps to start getting into Louis Bourgeois as we mentioned earlier, or whatever kind of contemporary art is out here that suit you need.

You have said that you spend time sculpting an infant on the camera, would you elaborate on this?

You know I take all kinds of images, but I think when I feel like I am most effective is when I am working incredibly slowly, when I am analyzing every little thing in front of the camera and that I perhaps even make things to go in front of the camera. Not necessarily sculptures but, manipulating things. I’m manipulating light, I’m waiting for light. That’s all I really need to say about it. If it takes me a week to get the picture, I’ll take a week to get the picture. I use $1,000 worth of 8×10 film to get one picture. Miles and miles of photographing in different light and different angles; figuring them out from behind the camera, and taking a long time to do it. That’s when I feel the richest, the most fortunate.

Coming back to the target and your aesthetic choice, at the Julie Saul show, you have one that is black and one that is white. I wonder why you chose to do that image in black and white and not the others, or why you thought it expressed it better in B&W?

In that one, the paint had been chipped off the metal frame that held the ply wood that was the target in the background. Behind that, there were these scrub bushes, these dark green sage bushes that actually turned black in certain types of B&W film, or certain types of filters. They were roughly the same size in the frame; the bushes were far away and the target frame was close and so these black areas, the black splotches, really mimic each other on the same scale. What I really wanted to do in that picture is compress space, or rather confuse 3D. You see these things near each other, you know one is in front of the other, but for a minute you don’t know what is in front of what. You get back to chaos, you get confused about the most fundamental thing, which is dimensionality. That can be very disorientating, and the reason why I wanted to disorient it, and I don’t know if I can explain this. It’s more of a notion than anything, I think if you confuse space in a picture like this one, you also confuse a sense of time. I wanted the picture to be about history in some way, I wanted that time to be shifted, not in any kind of literal way, but in a symbolic way. The symbolic way was the shift: space. That’s why that was in black and white, because if it was in color, the green of the bushes, you would see oh these are bushes and this is rust, and instead you see the rust and the bushes as relatively the same color. Can you see that in the picture?

Yes, is that what you are referring to when you say that landscape is a blank canvas that you project your image on it. Is that what you are talking about, it’s you dealing with this aesthetically.

Yeah, I think the camera works the opposite way you think it does, if you truly devote yourself to the medium, you direct your thoughts through the lens onto what ever else is out there. It’s not like you’re recording what’s out there , you’re actually projecting what’s out there and what I wanted to project was a chaotic history, a chaotic human connection to landscape that reference chaotic history. And so I know I projected that.

So it’s creating you’re own narrative in a way.

Yeah, yeah its my own narrative. Anybody else would take a picture in the other direction. Or take a picture of how unbelievably beautiful central Utah is. Or take a picture of the hunter shooting the target or whatever. And I want to take a picture of history in a symbolic way.

So, what are you taking pictures of now?

Good question, right. I have a great project here. I like taking pictures of things close to me. People think, “Oh he’s a Southern photographer.” Well, it’s because I lived in the South all my life and I don’t want to drive 1000 miles to take pictures all the time. Sometimes I like to take pictures nearby, so what I’m taking pictures of now is something that I think is very interesting, humorous, and funny. I’m taking pictures of the Lower Trenton Bridge. It’s famous for saying “trenton makes, the world takes.” They choose letters that are 13 feet high. It’s a vestige of when it was a manufacturing mecca. The Brooklyn Bridge, Washington Bridge, Queensburough Bridge, Golden Gate Bridge, many of their steel parts were made in Trenton. Of course not anymore, not since the sixties. That sign is still up, it’s still very much a part of Trenton. I am photographing it and rearranging the letters in the landscape to kind of figure out what it means now. What does a post-industrial northeast corridor that’s long been post-industrial say now?

You’re kind of poetic and romantic in my opinion. Are you kind of homesick photographically? It’s a different genre I think, it’s landscape but it’s different.

Yeah, it’s a different genre but I guess I look at it through my zoological and cultural anthropology courses. In New York City, there’s congestion, throughout the eastern seaboard, there’s congestion. It’s also kind of wild. Not only wild as in people, but there’s some really interesting nature that happens within this urban mecca. To me, it’s more interesting than nature what happens in a natural park. Human nature and the more nonhuman nature are in this sort of contact that marks our time in 2017. Maybe more than a natural park which is a token of a bygone era. A hermetically sealed thing, I’m not against them but I don’t find them interesting artistically. But, I do find urban environments, the weeds that grow through the cracks, and all the animals that survive among us very interesting. So I’m not really homesick to tell you the truth now, but I might be later. I’m kind of loving it actually.

Photography has changed a great deal since we have started, even in the past year or two, it is constantly changing.

Well, that takes us back to Central Range. If you look at Central Range, they look like composite pictures. They look like they’re dick pics of some sort of thing, I didn’t photoshop. And they are very influenced by the photographers of different generations, people like James Welling who is the father of or Ruffus Leywak. Some of these other photographers like Hanna Whitaker, who manipulates photographs to reference different kinds of sculpture and painting. They’re very much on my mind when taking pictures, but I kind of want to do it through the photograph to remind them or myself that the world is already a chopped up mosaic of different times and symbols. The world is fractured and put back together. We have signage, Walker Evans sort of did it too. So many different artists like Erin Systen. It’s totally a conversation with these other artists, but I do make a restriction . Restrictions make you think a lot. I don’t miss anything of photography today and I don’t miss anything of photography yesterday. It’s expanding in very different ways, and in a lot of ways it allows for some of the documentary forms to look new again.

Because I tell you, from my personal view, I was so tired when I started this magazine. Looking at any documentary photography and just because we’ve all seen so much of it. And I don’t know maybe two years ago, just all of the sudden it looks fresh and good to me because I’ve been seeing so much of the new photography, and I like it by the way I like all of this crazy stuff, then all of that stuff started to look so old and it’s all not well done it looks awful. You see a lot of things like this that aren’t well done so now it just looks so beautiful again.

I think we were done a great favor, photography was done a great favor by this sort of composite language. Because it made the non-composite language look fresh again. At least it gave it some room to breathe. It’s kind of an exciting time for photography in general. I think what we have to contend with is education. Everyone has the technological capability of making a sound image. You know, one that’s descriptive and the colors are light. Now that is true, what are we going to do with that awesome capability? It’s like if you were back in 1670 and suddenly everyone had the capability to draw like Raphael. That’s an incredible challenge for painting, and I think that’s why the study of photography is more important than it’s ever been. We almost communicate in images as much as we communicate in words.

Interview by Andrea Blanch

Andrea Blanch is the founder and editor of Musee Magazine. This interview was published in its issue 16 that came out in October 2016 and is available for $65.