‘Astronomical Notebook’ is the title of one of the exercise books , notepads and sketches of observations, among the archive documents and photographs that belonged to Russian astronomer A. P. Gansky. They were preserved as part of the fund assembled by his colleague, astronomer N. A. Morozov, in the Russian Academy of Sciences Archive.

The use of photography in astronomy was extremely important, having numerous advantages over visual observation. Daguerreotype images were replaced by the wet collodion process, which accelerated the exposure more than a hundred times and added considerable detail to the picture. The first images of the sun and moon, solar corona, solar spectrum and stars appeared. Techniques of photography were gradually perfected and photographic materials improved. The camera could capture the yellow, red and infrared areas of the spectrum, and photography was increasingly applied to practical astronomical research.

The astronomer, geodesist and gravimetric analyser Alexei Pavlovich Gansky (1870-1908) was born in Odessa and studied at the physics and mathematics faculty of Novorossiysk University (in Odessa), where he prepared for a professorship after graduation. At that time the Odessa Astronomical Observatory was headed by Professor A. K. Kononovich, a progressive scholar and talented pedagogue, also one of the first researchers in Russia to study astrophysics. Under his supervision A. P. Gansky devoted most of his time between 1894 and 1896 to photographing the sun and examining sunspots. Despite using very modest instruments (a 6.5-inch refractor), he took some exceptional shots.

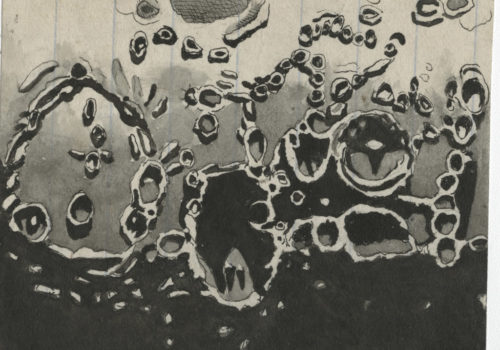

As distinct from the photosphere and chromosphere the outer area of the sun’s atmosphere, the corona, is very extensive: it stretches for millions of kilometres, corresponding to several solar radiuses, and its weaker prolongation continues still further. Density of matter in the solar corona decreases with height significantly more slowly than the density of air in the terrestrial atmosphere. The reduction in air density as related to elevation is determined by the earth’s gravity. The best time to observe the solar corona occurs during the complete phase of a solar eclipse. But in the few minutes this lasts it is very hard to record even the overall appearance of the corona, let alone specific detail. The eye of the observer scarcely manages to get accustomed to the sudden twilight before the bright solar ray appearing beyond the rim of the moon already heralds the end of the eclipse. Hence sketches of the corona by experienced observers during one and the same eclipse were often very different. It was even impossible to precisely define the colour.

The invention of photography gave astronomers an objective and documentary research method. The first successful photographs revealed many details of the corona: coronal rays, all manner of ‘arcs’, ‘helmets’ and other complex formations clearly related to active regions. The chief characteristic of the corona is its radiant structure. Coronal rays take a wide variety of forms: sometimes they are short, sometimes long, they can be straight or very looped.

In 1896 A. P. Gansky arrived at Pulkovo to make a closer study of astrophotography. In the summer of that year he was invited to participate in a Pulkovo Observatory research expedition to observe the total eclipse of the sun on the 9th of August 1896 from Novaya Zemlya. This expedition proved a success in all respects. In addition, Alexei Pavlovich collected photographs and sketches of total solar eclipses made by many different astronomers in different years. Based on analysis of all the collected scientific material he made important conclusions about the form of the corona being dependent on the number of spots on the sun. With the maximum number of sunspots the corona forms an unbroken luminescence around the sun. With the minimum number the corona is increasingly drawn along the solar equator and its light is correspondingly weaker. In this way Gansky discovered the change in the solar corona’s shape, phased in an 11-year cycle of solar activity. His prediction of the coronal form in the total solar eclipse of 1900 was brilliantly corroborated in subsequent years by many other astronomers. Thus Gansky drew attention for the first time to the universality of the 11-year cycle for active physical phenomena occurring in all strata of the solar atmosphere. Incidentally, he also discovered the 80-year cycle of solar activity.

After careful investigation it was established that a definite link exists between the coronal structure and certain formations in the solar atmosphere. For example, bright and straight coronal rays are usually observed above spots and faculae. Neighbouring rays bend towards them. At the base of coronal rays the chromosphere is brighter. This area is usually referred to as activee. It is hotter and denser than adjacent non-active areas. Above spots in the corona bright complex formations can be seen. Prominences are also often surrounded by clouds of coronal matter. At the turn of the 19th to 20th centuries, before plasma physics really existed, the observed properties of the corona seemed an inexplicable mystery. The corona proved to be a unique natural laboratory in which it was possible to observe matter in the most unusual and inaccessible conditions on earth.

In 1897 A. P. Gansky began attending lectures in mathematics, physics and astronomy at the Sorbonne, at the same time studying lunar photography with Loewy at the Paris Observatory. Subsequently he worked at the Meudon Observatory, world-famous for its classic methods of solar photography, with the eminent French astronomer P. J. C. Janssen. Over the years Gansky made nine ascents to Mont Blanc, where Janssen’s observatory was located, and carried out valuable observations there. He was commissioned by Janssen to study the solar constant with the aid of André Crova’s actinometer. Here, on Mont Blanc, Gansky made great progress in the search for ways to photograph the solar corona without an eclipse. He also carried out observations of Venus, assessing the period of alteration in its brightness and taking gravimetric measurements.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a search for new approaches, methods and technical resources in observational astronomy. French scholars Janssen and Flammarion were enthusiasts of astronomical observation from balloons and made many ascents using ‘montgolfières’, the hot air balloons invented by the Montgolfier brothers. Gansky went on balloon flights for research purposes twice in Paris and once in St. Petersburg.

In two summers, 1899 and 1901, Gansky participated in Russo-Swedish expeditions to determine meridian measurements on the island of Spitsbergen. For his work in the latter expedition he received a prize from the monarch, awarded by the Russian Astronomical Society to which he belonged from 1896. In 1907 Gansky was elected as its vice-president.

He spent 1900 in Potsdam, working in the astrophysics laboratory under Vogel, one of the founders of spectral astral classification. In 1903 Gansky began research into solar granulation. Only three astronomers in the early 20th century – Janssen, Gansky and Chevalier – succeeded in the unusual art of taking solar photographs, recording sunspots and granulations in fine detail. The quality of Alexei Pavlovich’s solar photographs and formations was unequalled until 1959, when the sun was photographed using telescopes sent to the stratosphere on air balloons.

Other observers’ inability to repeat such a high quality of images led to doubts over some of Gansky’s conclusions based on his photographs: for instance, the speed at which granules are dissipated. But life itself puts everything into focus. ‘He took photographs of exceptional quality, with a ‘nocturnal’ instrument, an ordinary astrograph mounted on the west tower of the observatory building, in the afternoon heat, the like of which none of the Pulkovo astronomers could achieve 60 years later using specialised solar telescopes with automation and electronic analysis of image quality. Moreover, Gansky obtained a consistent series of images in which you can track the biography of each granule, not just a few ‘record-breaking’ photographs. In the 1970s we had to create a stratospheric solar observatory weighing 8 tons and elevated by a helium balloon to a height of 20.5 km to achieve analogous results.’

In 1905 Gansky determined that the average lifespan of separate granules lasts from 2 to 5 minutes before they dissipate, to be replaced by new ones. He published his results in Pulkovo and Paris. Gansky’s works entitled ‘Photographs of Solar Granulation Taken at Pulkovo’ (1907) and ‘The Movement of Solar Granules on the Sun’s Surface’ remain unparalleled to this day.

In November 1904 a Commission for Solar Research (KISO) was set up at the Academy of Sciences, with Alexei Pavlovich Gansky as secretary. At the Commission’s first working meeting on 3 January 1905 he gave the main address, outlining a detailed programme for solar research and the need to create a high-altitude solar observatory in Russia. By the end of the 19th century it was obvious that further development of new tendencies in astronomical research (astrophysics, astrophotography, spectroscopy and solar observation) could not be fully realised at Pulkovo, due to geographical and climatic conditions. Gansky was the first astronomer in Russia to perceive the necessity of organising a solar physics observatory in the south.

The Commission charged Pulkovo astronomers A. P. Gansky and G. A. Tikhov with planning an expedition to research climatic conditions for establishing a solar observatory in the Crimea. Gansky himself devised a project, calculated costs for building the future observatory and suggested in articles that construction would be possible in the Crimea, the Caucasus or even the Pamir area. However, the inauspicious political situation in the country (war with Japan and revolutionary ferment) prevented this plan from being implemented in 1905.

In May 1906 A. P. Gansky and G. A. Tikhov applied to the Academy of Sciences with a proposal to send an expedition to the Crimea to examine zodiacal light and study the image quality. The scientific results of this trip were of little consequence, but the fact that A. Gansky happened to see N. S. Maltsov’s private observatory in Simeiz was probably the most fortunate consequence.

Pleased at this interest in his pastime, Maltsov offered to donate the observatory to the researcher. Alexei Pavlovich considered it expedient to transfer the gift to the Pulkovo Observatory. This made it possible to organise an astrophysics department in the south of the country. In time the Simeiz Observatory became the first Russian observatory involved in astrophysics research.

In early 1907 A. P. Gansky set off on his last expedition, to observe a total solar eclipse in Turkestan. For two years he carried out a series of observations to examine the surface of Jupiter. Here his talent for drawing proved very useful. The results of these observations have never been properly analysed.

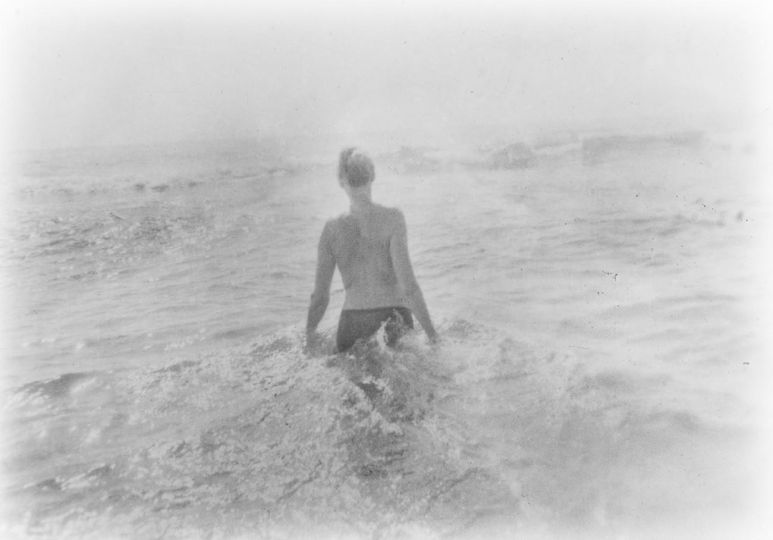

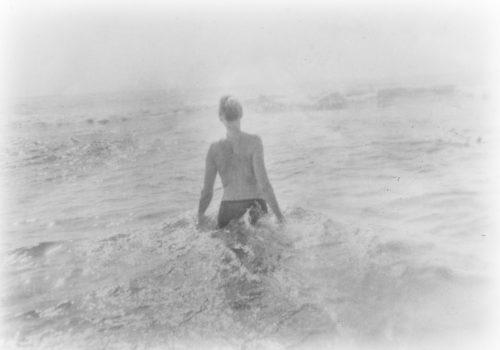

At the beginning of summer 1908 A. P. Gansky left Odessa for Simeiz to work on equipment for the observatory. After a month spent working to install the double Zeiss astrograph donated by N. S. Maltsov and taking the first experimental photographs he was tragically killed. According to G. A. Tikhov, in 1908 ‘one day Alexei Pavlovich went to bathe in the sea. In the rough swell he struck his head on a rock. He lost consciousness and drowned’. Gansky is buried at the Polikurovskoye Cemetery in Yalta.