The world is a ghetto. We of the first world forget this but it is everywhere, more common than not, people living below the poverty line in conditions too raw for us to fully comprehend. When we do consider it, we vilify or romanticize; we imagine it not as it is, for rarely do we venture into the world of the underclass. Yet artists venture forth, exploring lands unexamined and unexplored, discovering stories waiting to be told. Douglas Mayhew does just this in his first monograph, Inside the Favelas: Rio de Janeiro (Glitterati Incorporated).

Mayhew became interested in the favelas while doing volunteer work in the recreation room of the children’s ward at the Miguelo Couto public hospital in Rio. A child came in with a gunshot wound to the arm, a wound that had become infected after time had elapsed before the child could be brought to the hospital from the favelas. Needing to understand how such a thing could be so, Mayhew took up with Marcelo Castro as a guide and climbing partner. Together they entered into the favelas with his camera, documenting life as it is lived in a battle zone for the War on Drugs is not fought just at the borders but in the ghetto as well.

Mayhew provides a detailed account into the history of the favela, which houses 20 percent of the population. And population is on the rise, as the figure jumped 65% from 2000 to 2010. They are without fully functioning infrastructure, lacking in basic sanitation, water works, sewers and drainage systems, pavements, open roads, and public lighting. Homes are built by those who inhabit them, creating a patchwork pastiche of raw materials set together as best possible.

The first favela in Rio was created by veterans of the Canudos Civil War of 1898, when the government failed to provide housing and back pay. They settled near the old center of town, sharing the hilltop with the Brazilian War Ministry’s office complex as a symbol of protest. The government ignored them as they developed the South Zone to attend to the demand from well-heeled residents. The government turned a blind eye to the favelas, which continued to expand, making them ripe for control by drug warlords.

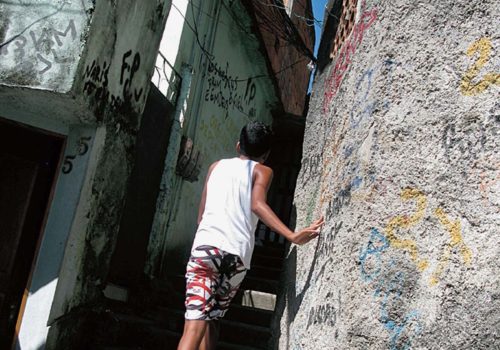

Mayhew brings us deep inside this world, into a landscape that is raw, brutal, beautiful, a world of basic human survival. Many photographs were taken with the permission of the favela’s reigning drug lord. Through Mayhew’s lens we do not see the people themselves, we are not privy to their stories as individuals. Instead we are given a look at the world in which they live, Mayhew being our personal guide. Through his photographs we travel step by step, looking at the makeshift architecture, the spontaneous energy of graffiti written on cracked and crumbling walls, of countless black electrical wires snared in massive spider webs, of makeshift stairs everywhere, a feeling of permanent transience, of the utter fragility of life struggling against the elements at every turn.

We see no faces, except in Mayhew’s photographs of street art, making these portraits of the way artists see themselves, the stories that are left behind as we read the writing on the walls. We see one small child sitting on steps of poured concrete, wearing a Mickey Mouse tank top, and shorts with bears dressed in nightclothes, and on his head is a yellow motorcycle helmet, his small hand gripping it in place. It is an image like this that hits, this small life force amidst the empty streets, the knowledge that a new generation is born into the heaven and hell of the mythology that life in the ghetto tells its young boys and girls. We can never know what it is to live in the crossfire, to live and die in a land dedicated to a war without end, a land that is the darkest underbelly of the land where the girl from Ipanema goes walking along.

Miss Rosen