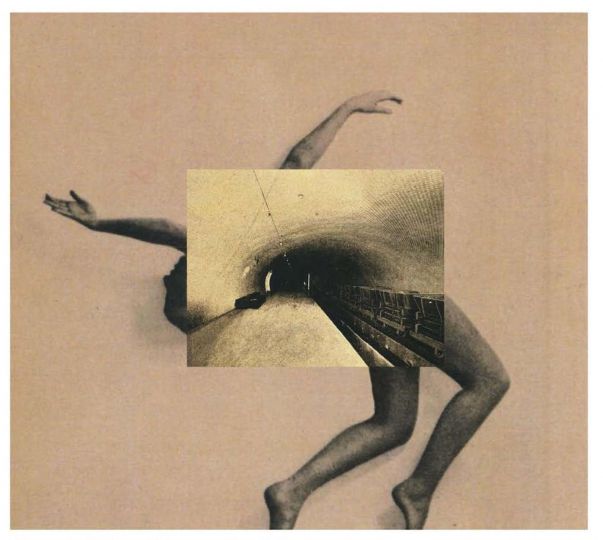

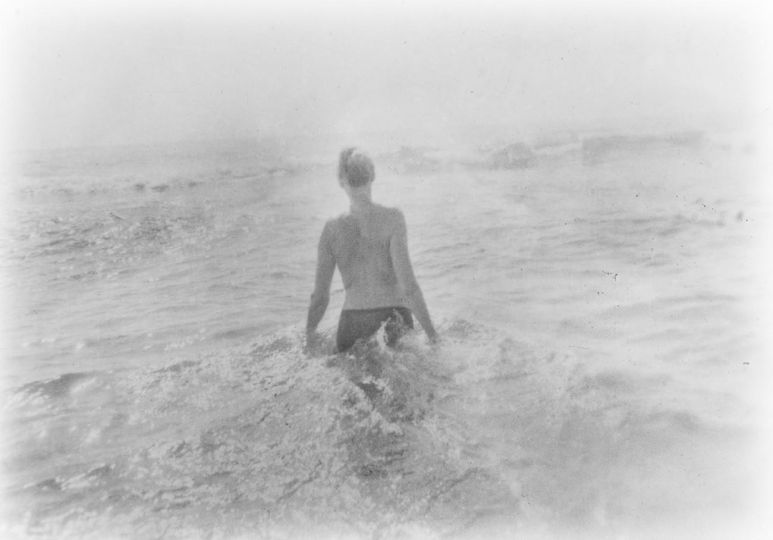

Photo series by Melissa Renwick – concept collaboration with Jennifer Friesen

While still choking on the cloud of fuchsia powder that was just slapped across my face, I had the hands of a dozen faceless strangers grasping at every crevice of my body.

Trapped in a near stampede in the village of Barsana, India, there was nowhere to move. The streets ran like a torrential wave, and despite the fact that I was standing on the sidelines, I was swept into the deluge in a matter of seconds. The tiny road was packed with hundreds of men who pressed against me, groping me from every angle. A hot, stinging panic swelled up in my throat, and as if outside of myself, I heard the panic strangle my cries of protest and twist them from indignant anger to pure fear. The men, indistinguishable through their painted faces, must have heard it too, because they dug their fingernails deeper into my skin, balling their knuckles over my chest and backside. I threw my fists around wildly, hardly aware as I connected with their jaws, but I still couldn’t move forward without being surrounded by another slew of untraceable hands. It was another 15 minutes before I found a stoop to climb up on, where I could calm my shaking hands and wipe away the terror that streamed down my cheeks.

And it was all because I stepped out into the streets during the Lathmar Holi, and because I am a woman.

Holi is a Hindu festival held every year in India and through Nepal – it’s a celebration of spring, a celebration of love, and a celebration of good triumphing over evil. Photos of Holi saturate the globe with dream-like billows of coloured powder and painted faces that echo an ever-present laughter. So how has it become a living nightmare for the women who step outside of their doors?

“In any village in India where Holi takes place, whether it’s because of religious or cultural sentiments, there are a lot of differences between how the men and women celebrate,” explained Jasminder Oberoi, forerunner of JAS Fotography, who has been leading photo tours to Barsana and Nandgaon, where Lathmer Holi is held, for the past three years.

“When you visit Barsana, you see women with their faces covered, which means that they are not supposed to be mingling with people openly,” he says. “Men, on the other hand, they have the right to treat women the way they want. And on Holi, they really go all-out in terms of misbehaving. It gives them the opportunity to do whatever they want – and they go overboard. They don’t only tease, but they try to manhandle and exploit women to the best of their capabilities.”

Oberoi now lives Faridabad, a city just on the outskirts of Delhi, with his wife and three children. But, while growing up in smaller towns in the state of Madhya Pradesh, he recalls older boys trying to teach him that Holi was the acceptable day for men to “have fun” at the expense of women.

“It’s sad, but it’s a harsh reality,” he continues. “In India, menfolk look forward to Holi for a different reason than women do.”

News reports emerge each year, as women describe being groped, assaulted and raped by men in the streets during Holi. This year, a 14-year-old girl was nearly dragged into her neighbor’s home in Delhi under the guise of “playing Holi,” and three women were stopped and groped by a group of eight men when their auto rickshaw stopped at a red light. And most disturbingly, in the Raniwara village in Rajasthan, a 15-year-old girl was kidnapped and raped by three men, aged 23, 24 and 25, after she resisted when they tried to put Holi colours on her face.

And these are just a few of the cases that were reported.

“A lot of the women do not tell the people ‘No,’ because they do not want to make too much of an issue out of a situation that might be termed ‘accidental,’” Oberoi shakes his head, visibly disturbed by his own observations. “So they try to keep quiet, and the boys and men take advantage of that. It’s an unfortunate situation, but that’s just the way things are here … that’s the way things are.”

Theresa Thomas, a corporate lawyer in Delhi, decided to go along to the street celebrations in Barsana and Nandgaon this year for the first time. Born and raised in Southern India, Thomas moved up north seven years ago, the region where Holi is predominately celebrated. Through all these years, she says she has never seen a woman in the streets alone during Holi, because generally women stay indoors with friends and family, whereas men celebrate on the streets. This year, much like Melissa and I, she wanted to see the festival the way the world sees it through the photos.

“I was very, very scared to go [to Barsana and Nandgaon],” she continues. “These people in the villages do not interact with women on a daily basis, they’re often sexually repressed. So for them to touch someone and put colours on them – there are almost always sexual undertones to it.”

She describes the experience at Lathmar Holi as a lot more violent than what she was used to. She says strangers slapped her face with colour and deliberately threw the paint, which can sometimes be toxic, into her eyes.

“If you put your head down to avoid the colour getting in your eyes, they just came from below and aimed more into your eyes. There is just so much more respect for personal space when you’re with people you trust.”

After Melissa and I had endured the two days of Lathmar Holi in the small villages, we quickly realized that we were experiencing the festival from a man’s perspective. In public spaces, men run the streets; so we got on a bus and headed Rajasthan to celebrate the official day of Holi, March 17, in Jaipur. There, we entered the private sphere of women’s homes to photograph them in an intimate setting, and set them against a black backdrop to contrast the chaos of what Holi is like on the streets.

Inside the stone walls of families’ homes, surrounded by fences standing 8-feet tall, we were engulfed in a scene filled with the true, genuine laughter of children who were completely at ease. When they pressed their crimson palms to our cheeks, it was with a warmth that shimmered out through their eyes. When buckets of violet water were dumped over our heads, we laughed along with them, because it was never done in malice or with sexual depravity.

There were no furtive glances cast over shoulders and no intrinsic need to shy into corners. Here, we saw the fabled beauty and joy of Holi, and for that I’m truly grateful. But why is it that inside the home is the only place women can experience such a beautiful festival without fear?

“Frankly, it’s the Indian approach to take,” explains Thomas. “Instead of telling the man to correct it, they just tell the women to stay at home. It’s obviously not the right solution, but they find it easier.”

The problem is pervasive, and to some extent, it’s permissive. Many of the rape and assault cases that emerged this year weren’t even filed by the police for several days after each incident, despite being reported on the same day. Something needs to change, and the world knows this, but in a country where men and women are often unable to freely interact with each other until adulthood, the root is buried deep.

“The attitude that men have towards women in India has to change,” Thomas says. “That depravity, that feeling of not having seen them before, or wanting to physically disturb somebody’s personal space – that has to change. It has to be a gradual process that slowly evolves with time, but without that, nothing will matter. They need to respect women. If that respect comes, I think everything else will follow.”

Jennifer Friesen

http://www.shiftingground.ca

http://www.melissarenwick.com

www.jenniferfriesenphotography.carbonmade.com