A book doesn’t always need a title, and when it does, the simple name of the author is often enough. Nor does it need a thick cover, a bunch of pages, essays and palaver. The eponymous book by American photographer Margaret Durow, published by Setanta Books, is a work of fragility and subtlety, of a certain grace taken from simplicity.

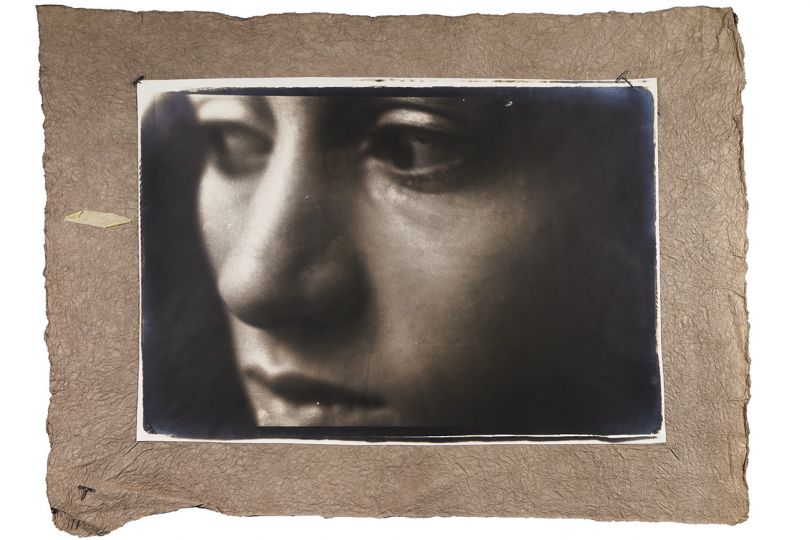

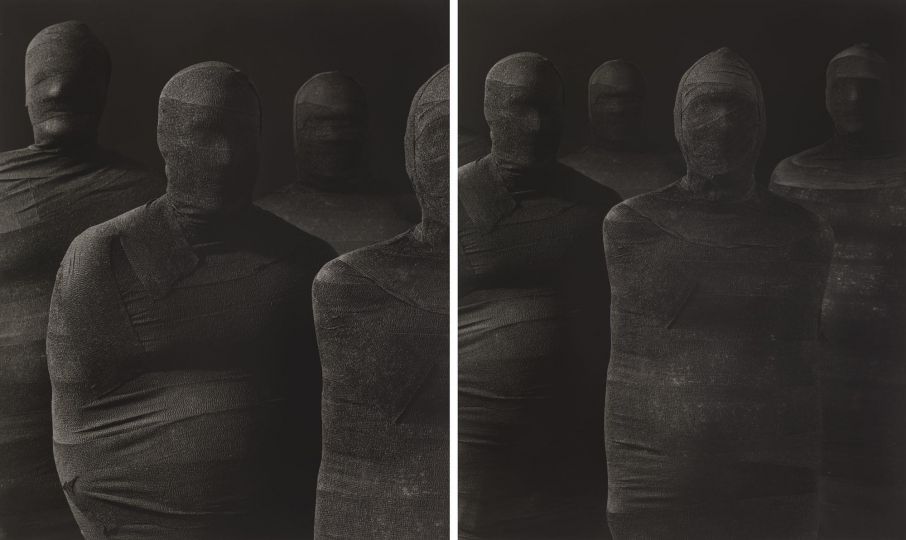

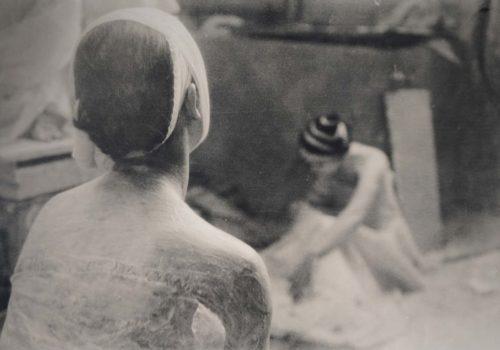

A small format, a simple magnetized brick-colored cover holds a small notebook of coated paper. Forty-eight pages, with no essays or captions, are needed in order to preserve the vision. Photography in its simplest form. From the outset, the book formulates a mystery, an ambition of sensuality beribboned with solitude. The first pages open on the body of the photographer herself. Images seems softened in the penumbra, with plays of light blocking the lens. The frail body of the photographer stands out from a short halo, a ray as thin as a winter sun. The penumbra is not broken; the body slips in or out of it, no one knows.

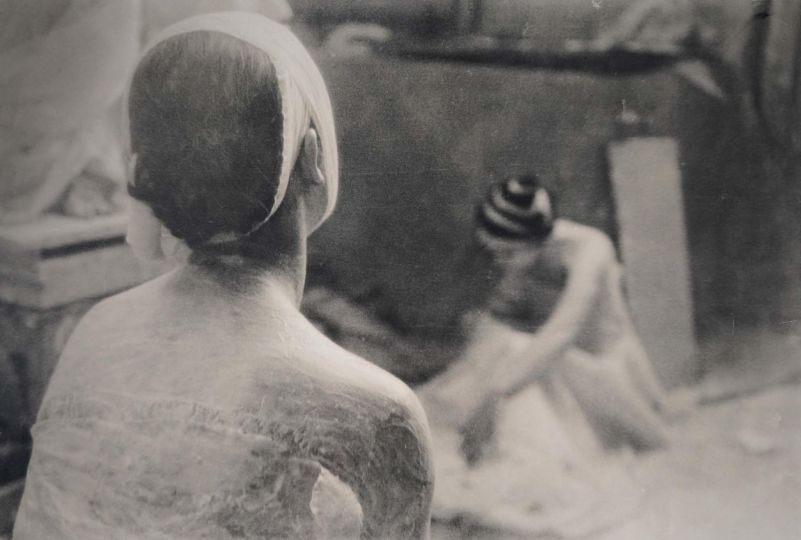

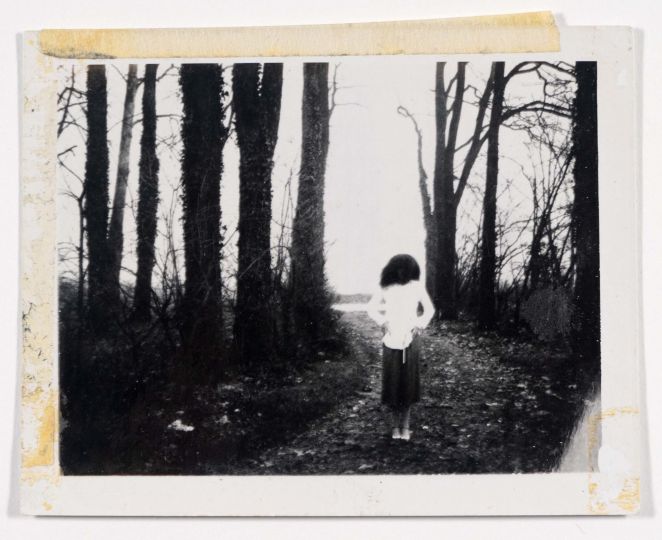

Durow’s subjects are herself, but this inwardness does not tilt towards egotism, narrative art or absurdity. She photographs her body, her scars, her painfull spine, more rarely her face, and quite often her silhouette. The landscapes of Wisconsin, where she lives, are somehow superimposed on her portraits. Taken alone, these landscapes would remain as a palette, a lacunar drawing of nature. But in Durow’s work, they are recomposed with portraits, or rather one prolongs the other, in order to read each photograph like a vivid emotion, captured by the lens, held by the paper, revived by our eye. Interiority, this psychoanalytical word, a little clumsy and repeated, finds in this book a euphonious echo. It simply makes sense.

First of all, interiority evokes a form of healing: “When I was five years old, a benign tumor was discovered in my lumbar spine, which gradually caused my spine to curve over time. In 2007, I experienced severe complications from the surgery that straightened and fused my spine in place. Eleven years later, I underwent more reconstructive spinal surgeries that were unsuccessful and caused additional impairments. Photography allows me to express how I feel, and transform the pain and isolation of my deformed and disabled body into beauty and strength”.

For the artist, photography forms an ointment, a form of operation, this time a successful one, that sews, rewelds, brings together the disparate forms of her body. This cathartic function appears suddenly in some photographs, like those in the preamble and in the conclusion of the book. A traumas that couldn’t be cured—and that scalpels have aggravated as the years go by—mark the photographic gesture. It’s sometimes called “living with the evil”, “enduring the pain”, “carrying a burden”.

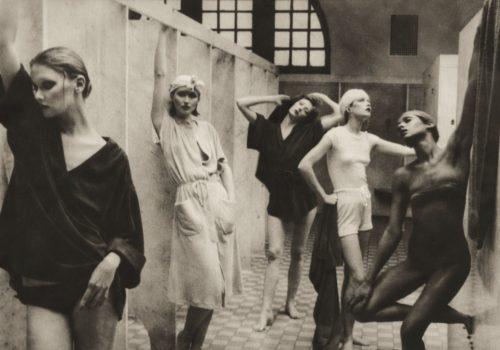

To put it simply, photography allows Margaret Durow to accept her body. It first makes the readers understanding that healing is no longer possible, and most important of all, it affirms that her body is not a single scar. There resides her force, her beauty. Her handicap is overwhelmed by an astonishing combination of lightness, and sometimes sensuality. Durow’s stagings goes to the essential: to put into shape one’s own beauty, discovering in her body much more than a bruise. This body suddenly awakens desire (Winterlight, undated), floats in a silent mist (Sunset Water, undated). Everywhere it escapes its contusion and shines.

Somehow, to flicker is to shine. Durow’s photography often seems to lose its footing, to falter in joy, lull or more rarely, sadness. Her work recalls the elementary astonishment at the simplicity of life. Without falling into prophetic tones, without pouring into ontological discourses, this simplicity often comes to us by the smallest manifestations. For Durow, all it takes is the migration of a colony of birds that has become a punctuation mark on a telegraph wire; the blizzard covering the thick purple lights of an abandoned square; the stroll of a loved one in a deserted land. The book blossoms there, between two magnificent scars, full of a profoundly poetic life, because everything is entirely inhabited.

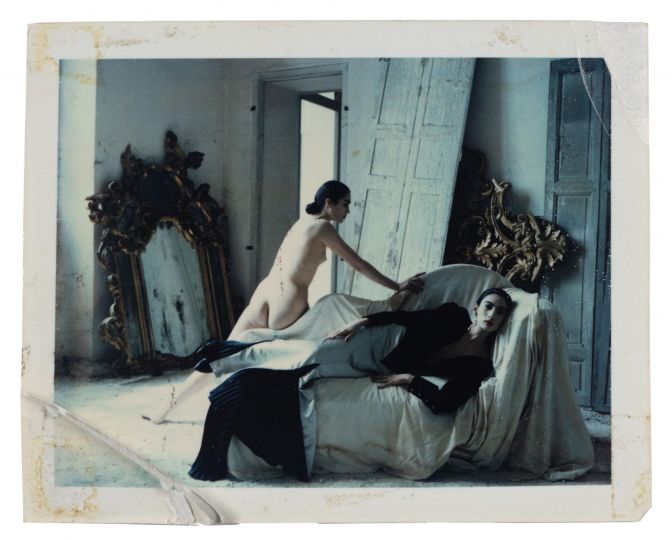

Margaret Durow can be related to Saul Leiter. Both of them are tirelessly walking their daily landscapes – the lakes of Wisconsin for her, the East Village block for him – convinced that it doesn’t need to go far to grasp what resonates within. There is also in her saturated, flayed, veiled and floating color a connection with Leiter, Bernard Plossu or Nan Goldin. At last,t there is a whole autobiographical gesture that connects her to Francesca Woodman, in this astonishing way of hiding herself to herself, as well as to others, in complex compositions.

But beyond comparisons helping to understand a work, and so poor to understand its content, her photographs give the tenacious impression of an environment, of a solid, coherent, living ecology of emotions. In this sense, she has composed a successful book in the way it opens up a part of her thoughts, a subtle breach in her inner life. To think that in about thirty photographs, one can experienced the joys, sorrows, loves, calmness and silences of another, isn’t it striking?

Arthur Dayras

Margaret Durow

Eponymous book by Margaret Durow

Setanta Books, 2020

48 pages, 25 €.

More informations on Setanta Books

* The titles are taken from the publisher’s website, the book does not include any.