After I graduated from high school in Philadelphia, I enrolled at the School of Commercial Art and Lettering. At first, my hand was shaky, but after some months I finally looked at my first sign, which read: “FRESH FISH.” From 1934 to 1937, while still at school, I worked as a caricature artist in Atlantic City. 1937 marks the beginning of my interest in photography, which grew considerably the day I won first prize in a weekly photo contest in the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger. Shortly thereafter, the first photography books issued by the Farm Security Administration became my bible. I was particularly impressed by Walker Evans’ photographs. The world of Harper’s Bazaar also exerted a pull.

Later on, in New York, I met Robert Frank at the Bazaar studio. Since I lived far away, he invited me to stay at his loft, in the company of his nine cats. He had just come from Switzerland and lived alone. New York delighted and surprised me at every turn. Wherever you went, there was something to discover. My photos, at first rejected, started to appear in U.S. Camera. My work was being accepted; it often just seemed unreal to me. I showed my photos to Walker Evans. A beautiful copper kettle in his tiny office at Fortune magazine conveyed all his stability and eloquence. “You wouldn’t want to photograph fat women?,” he asked me. Later on, he cautioned me: “be careful not to get contaminated.” He responded to my need to continue photographing with commercial assignments. I worked for the press, including Harper’s Bazaar.

1946 to 1951 were important years. I photographed almost daily, and the hypnotic dusk light led me to Times Square. Several nights of photographing in that area and developing and printing in Robert Frank’s darkroom became a way of life. “Whatta town, Whatta town!,” Frank would shout.

My work was included in Edward Steichen’s exhibition In and Out of Focus. Afterwards, it was just work, work, and more work. “My boy,” Steichen said to me, “go out and take photos, and leave the pictures on my desk.” The order was reinforced with his fist striking against the glass top of his desk. It was a miracle that the glass didn’t break. I got a taste for and accepted the offers of the 1950s and 1960s. Life Magazine, Cowles Publications, Hearst, and Condé Nast allowed me to pursue my personal work. Oftentimes, I would bring a 16mm camera along with my Leica, and photograph New York streets. The results were never shown in public, and the negatives were stashed in a corner.

In 1969, I felt the need to see new places and new faces; I needed a change. I tried Europe. I returned to the States in the mid-1970s, and was stunned by the transformations that had taken place. I started to photograph New York again with a renewed zeal, almost equal to that of my early days. Harry Lunn’s purchase opened up the world of galleries to me. Once again, I found myself attracted to drawing and, as if by magic, the photographer became an artist!

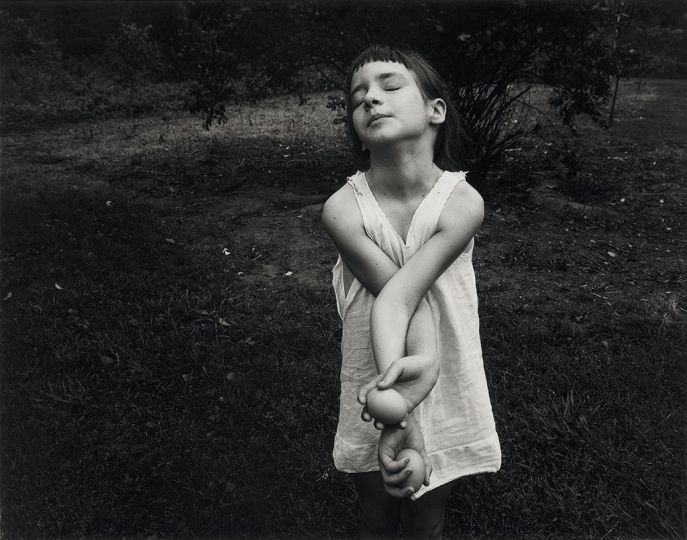

My eyes search for people who are grateful for life, people who forgive and whose doubts have been removed, who understand the truth, whose enduring spirit is bathed by such piercing white light as to provide their present and future with hope.

Louis Faurer

October 2, 1979

Text published on the occasion of the exhibition Louis Faurer – Photographs from Philadelphia and New York 1937-1973 presented from March 10 to April 23, 1981 at the Art Gallery of the University of Maryland.