Julia Scully, who after 20 years as editor of Modern Photography magazine wrote an acclaimed memoir about her Depression-era childhood, when her mother put her and her sister in an orphanage before moving the family into a roadhouse in a remote part of Alaska, died July 18 at her home in the New York City borough of Manhattan. She was 94.

Her death was confirmed by Jana Martin, a daughter of Scully’s companion, Harold Martin, a photographer.

Scully began working at photography magazines in the 1950s and was hired to be editor of Modern Photography in 1966. The magazine was as devoted to the technical side of photography as it was to its aesthetics. Scully focused on the latter, and under her tenure, the magazine was instrumental in the emerging recognition of photography as art.

She started a section of the magazine called Gravure that asked renowned photographers such as Irving Penn about the circumstances and artistry of their pictures; wrote a column called “Seeing Pictures,” in which she described the work of photographers she admired; and reported on exhibitions.

“Gravure and different series that we did later just kind of took up the idea of photography as an art form,” Andy Grundberg, a former picture editor at Modern Photography and later a companion of Scully’s, said in a phone interview.

He added: “Julia was friends with photographers, had been married to a photographer and was in the swing of things at a time when galleries were being established for photography and museums were getting more interested.”

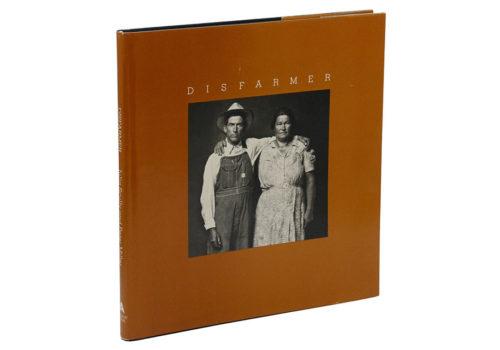

While leading the magazine, she published a series of arresting portraits by Mike Disfarmer, an obscure photographer from rural Heber Springs, Arkansas, who had died in 1959. Disfarmer’s customers came to his Main Street studio, with its plain backdrops, to celebrate life’s transitions — for 50 cents a shot — in black and white.

Scully was alerted to Disfarmer’s work by Peter Miller, a local newspaper editor.

She and Miller collaborated on a 1976 book, “Disfarmer: The Heber Springs Portraits, 1939-1946,” which presented 66 of his photographs. Writing in The New York Times Book Review, Peter C. Bunnell wrote that the pictures “are not nostalgic, but haunting, suggesting daguerreotypes of strangely familiar yet unknown relatives. ” He added: “Julia Scully’s sensitive text illuminates both the man and the place.”

In an essay the next year in Aperture magazine, Scully wrote that there was a “conscious intent, rather than a naive artistry,” behind Disfarmer’s portraiture, helping him to create photographs with a “piercing clarity.”

Excerpt from the article by Richard Sandomir originally appeared in The New York Times.