José Maria Sert, a Spanish muralist who moved to Paris in 1900, experienced photography as a constant companion. We know nothing about his first encounter with the medium, nor when it was that he decided to carry out through photography transfers from reality to the imagination – from live sampling to formal interpretation – any more than the point where this went from being a simple mnemonic convenience to a genuine working method, with the deliberate conception of poses and stagings as a basis for making images, and still less what favoured the shift from proofs to perfected prints. And one also might note the ultimate change in status of his photography, from an intermediate step to an end in itself. What explanation can be suggested, other than the euphoria of forms obtained by means of photography alone, and the degree of liberty that was to be found in a small, autonomous format, as opposed to the expanses of walls and the constraints of spaces, not forgetting the exclusive wealth of the ranges of greys, for a painter who was familiar with the nebulae of light and shadow in grisaille, and who worshipped gold?

Here and there we find reports of a camera being permanently slung round Sert’s neck during his many journeys to Italy, Russia, Scandinavia, Africa, China and America, though he never directed it towards the sphere of intimacy or the production of memories, which did not interest him. He was in search of inspiration, and motifs he could use in his murals – trees, panoramas, animals, water, crowds – when he was not making pilgrimages to his revered sources of classical art, sculpture, and ancient urban remains. As to his intensive practice of studio photography, this was a secret chamber whose usages and functions in technical matters we have little knowledge, although the absolute control of a master’s eye is evident. As in his painting, there was just one artist, and “assistance” did not imply “collective creation”.

Is Sert a case study? He was a celebrated painter in his own lifetime: around the world, officials and aristocrats of rank and money vied for his decors. He has since fallen out of favour, or failed the test of modernity. It is his photographic work that has now won him an unexpected renaissance, and a new positioning in the history of art.

This is a revelation to which Michèle Chomette has been attached since her discovery of Sert’s photographic studies at the start of the 1980s. And it is this paradox that the public, the critics and the institutional world will be able to appreciate in the spring of 2012, in three exhibitions highlighting Sert’s methods, with photography as the essential key to his pictorial work between 1900 and 1945:

• The Titan at work, at the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, March 8th – August 5th • The other side of the story – a painter put to the test of photography, at the gallery, March 14th– May 12th • From one palace to another, between photography and painting, Stand E12, at Art Paris, March 29th–April 1st

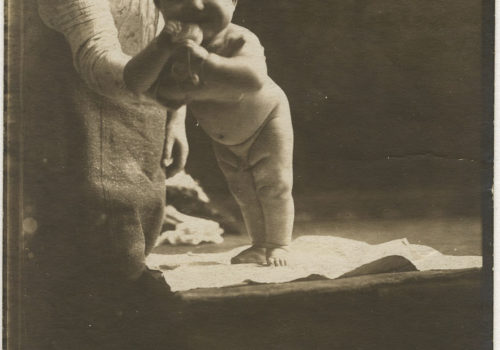

This was not a case of photography being applied to painting, in the ordinary sense of the term, or else being so strongly applied that a fusion took place, so that its appositions to the wall, on whatever scale, dictated the most minute deposits of pigment, incorporating the different elements studied from one motif to another: from the acrobatic posture of a man’s body to an unfolding wing or the frame of a boat, from the fall of a drape to the folds of flesh in a baby’s thigh, from a mass of bovine haunches to an ascending piled-up cortege of bishops, or the expulsion of the moneylenders from the Temple. Or again, more allegorically, from the sporting contest to the warriors’ charge, from orientalist fantasy to a celebration of modern industry, from the symbolic representation of humanity’s great principles (Justice, Power, Peace) to episodes from the Bible. These graphic supplies were extracted one by one, repetitively, from the repertoire of the elaborate attitudes that Sert imposed on his models (his assistants, in general), or articulated wooden mannequins, or flexible Neapolitan tow and wire figurines, in choreographies, often aerial, supported or unbalanced, accompanied by all sorts of trivial objects or maquettes on the stage of in the secret theatre of his studio. This osmotic duplication is such that one can rather see painting as being explained by photography: if one unpacks his dense compositions, zone by zone, motif by motif, it is photography that provides an exegesis to painting and supplies the key that opens up and enriches an understanding of Sert’s œuvre, whatever the workmanship, style, aesthetic conventions, themes or object.

Such cut-and-paste operations do not take place directly between nature and painting, and the less so as the former only rarely gave Sert the examples he sought – at most, hints to be metamorphosised by his penchant for excess on the mural scale – but it functioned perfectly between photography and painting, provided that, for the purpose of the image-making, he produced complex, detailed scenes and dramaturgies in which everything was under tension, under torsion, so that improbable photographic images resulted. And here we encounter a second paradox: the small-scale photographs (between 9 x 12 cm and 24 x 30 cm) were matrices that had to be followed with exactitude in their conversion to giant proportions. It may thus be considered that the painting is here an enlargement of photography.

Photography has many specific properties that are unnecessary and unusable in the painted work; but Sert treated them, and their printing, as if their production were an end in itself. And this dual status of photography, in his work, was a gift from the gods. The force of its attributes, which he could not elude, was what gave it back its autonomy – after being pressed into the service of painting – and its intrinsic power of fascination. Brutal framings were dominated by obliques, high- or low-angle shots of great audacity; deep blacks, greys, almost pallid, were accentuated by techniques of chemical erasing, and a moving energy of shadow and light. These characteristics derive from photography itself, but their emphasis is Sert’s alone.

The other escape route for photography, and by far the more important, is what is in the image. And it is visible only in the photographic studies, in that which is out of frame in the paintings; the other side of the story, for example the context of the studio, around what constitutes the object of the image-making (the motif that is to be painted), with the assistant supporting the model’s pose, or even – and this made it possible to compose an extraordinary life sequence of eleven images – the nursemaid who suckles the posing child; the sketches and finished paintings (which are invaluable for dating purposes) in the background; and above all the entire stage and its machinery: the walkways, the pulleys, the bars for the suspension of the mannequins and the spikes that hold up the figurines. These accessories, often odds and ends, dominate the photographic image. They structure it and qualify its aesthetic value, like experimental or surrealist inventions. Without overlooking the irrelevance – though for us it is a formal element – of the white circles left by the drawing pins under the enlarger in the corners of the prints, these crude studio objects exude a period aura as unique pieces, quite carelessly manipulated, often overlaid with a scale grid and reworked in black, white, red or blue pastel to emphasise their lines of force.

Painting’s loss was photography’s gain !

Michèle Chomette translated from the French by John Doherty

José Maria Sert (1874-1945)

The other side of the story

a painter put to the test of photography : studies, 1900-1945

Individual exhibition: 14 March – 12 May, 2012