For Jim Lee, storytelling was always at the heart of his work and his life. Lee was born in 1945 to parents who were both MI5 operatives marking a beginning to a life that followed anything but a conventional path. At the young age of 17 he decided to move to Australia where his interest and passion for photography sparked. His time in Australia was full of youthful adventure but, more importantly, it opened up a love for photography that allowed him full creative scope for his imagination. Back in Swinging London he began photographing bands such as The Who, The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. His portfolio and reputation grew and Lee became in demand as a fashion photographer working with personalities like the young Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour and collaborating with such influential fashion designers as Yves Saint Laurent and Gianni Versace. Today, Jim Lee is an established art photographer but still collaborates on many advertising and fashion projects such as covering fashion shows for celebrity designers Alexander McQueen and Zandra Rhodes. Lee’s narrative-led, both surreal and filmic, and often risqué images create remarkably alive compositions begging the viewer to “reach beyond the frame.”

You did not start out with the dream of being a photographer – you were more interested in the moving image and eventually did work extensively in film – so how did you end up in this medium?

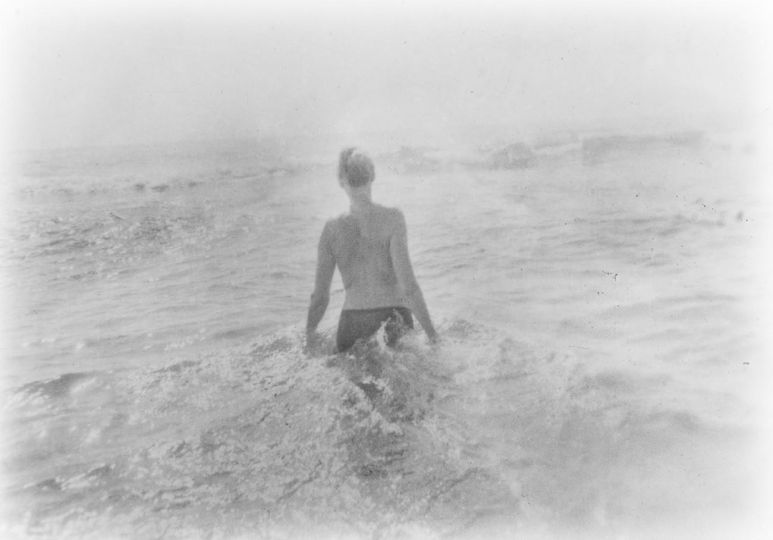

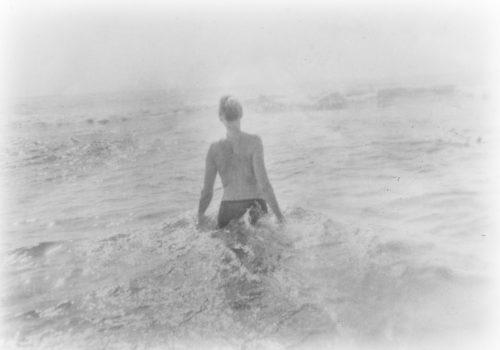

My wish was to be a painter and I went to art school, but I was too heavy handed. My grandfather was a very good painter, and so was my mother, but I did not have the aptitude. I began to see French art films, for instance Sunday and Cybèle (1962). In them, I saw ramifications of my own life, and the emotional quality of these struck me. It was then that I became interested in being a filmmaker, but I didn’t know how to go about doing it. Photography seemed to be a way to get there. That’s why the pictures I took in the early days were more like lm stills; that work was a plea to be a filmmaker.

You had a very interesting upbringing. You come from a line of English royals, and your parents were agents in MI5, the British security and intelligence agency. How do you think your early life influenced your later artistic pursuits?

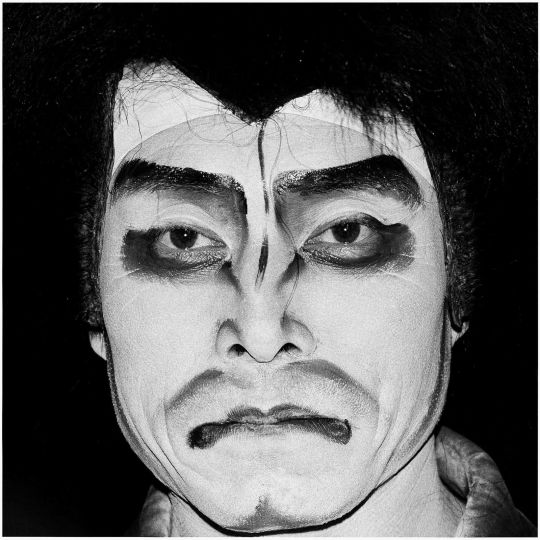

It added color and another dimension, which made my life exciting, there’s no question about that. I actually did not know about my regal connections until much later – my parents kept that quiet. One of the main things it added to my work was the sense of ambiguity, hidden and layered meanings; I like to lay trails in my pictures. I think that is directly associated with the life I had with my father, the effect of living a double life.

I can remember the first time I discovered what my father did was after I had applied for a visa for a trip to Russia with my grandmother. Over lunch he told me, “You know, you can’t go to Russia,” but I had not even told him of my plans. When I asked how he knew, he said that my papers had come through his office. “What is your job?” I asked, “You either run a brothel or you’re a spy for this to be such a secret.” He answered, “It’s the latter.” Over time I began to realize how many troubling situations I had been in and was miraculously saved; it was because he was keeping an eye on me.

How did art release and relieve your frustrations as a young person with dyslexia?

When I had dyslexia it was not treated the same way it is now. It was a different time and a different learning system, not as sensitive to such disorders. Photography definitely was good for me. It is a matter of trial and error, and I really enjoyed that. It is nothing like the standard learning system.

Your career as a fashion photographer developed during the 1960s, at the forefront of a new culture of creative industry, including fashion, media, and art. How do you see that industry changed today? Where do you see it going?

The industry today is a much bigger business and more streamlined; it is controlled more by clients than by creative people. In my day, going back to the 1960s, photographers were highly cherished, and if they were creative they were given the opportunity to express themselves. Today the fashion industry is truly an industry, run by money and less by imagination. I’m not the slightest bit interested in where it’s going.

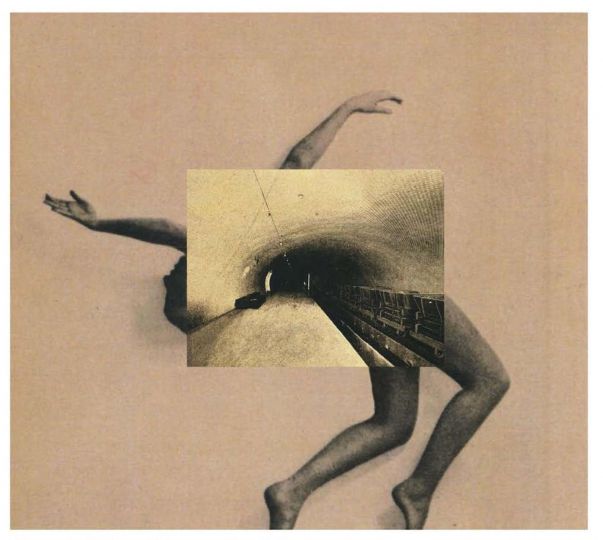

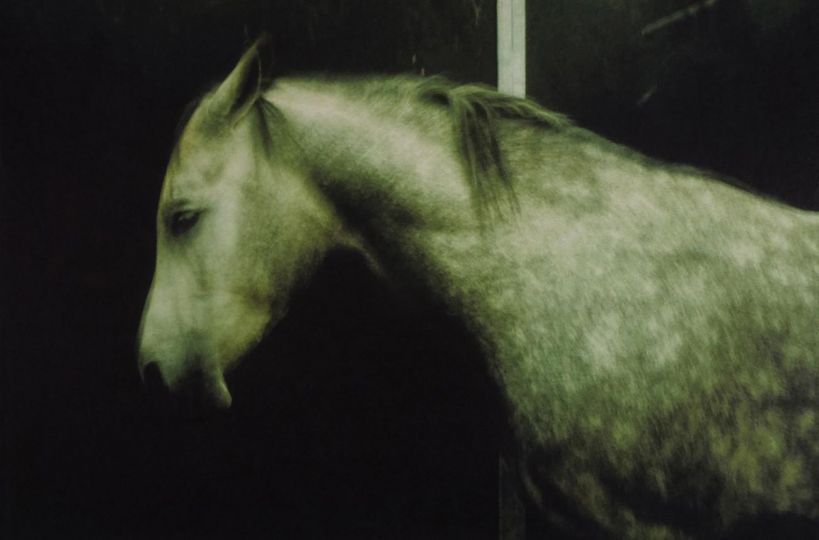

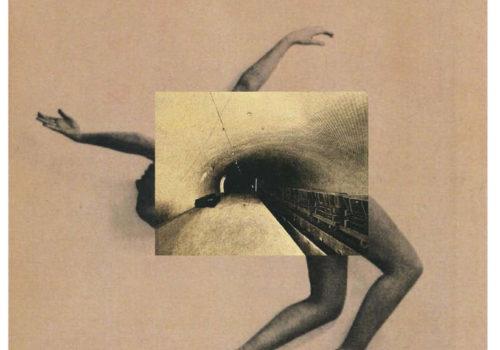

In your book Arrested, you say, “I like to create striking – even shocking – images that make you read the story behind the picture. Images that make you see beyond the frame.” It is so true that your pictures tell stories. Why is this important for you?

I believe in maximizing the benefit of the frame by going outside of it. I want to make people imagine the image extends beyond the frame. When you have a designated space, the richer you make it, the more you can say in a single image. If someone’s going to look at the picture more than once, you want to make it worthwhile.

I try to think of putting many different elements into a single image, without making it busy or complicated. First I think about the reasons for making the picture. Then I think: How can I layer it? How can I extend it psychologically? How can I create a depth of looking? How can I create atmospheric lighting? What about the design? I am trying to come up with something that you can look at, something that you can cross-examine and challenge, something with merit. Otherwise it’s a waste of my time and other people’s time.

There is an irony in the fact that you are a very successful fashion photographer, yet I read that you actually are not very interested in clothes. Why do you shoot in the fashion arena?

Well, it was a way of being able to get into the business of photography. I needed to learn more about the camera and lighting, but I also needed a business where there was work to be had; I needed to make enough money to survive. My options were fashion or reportage. I could have gone off to shoot in a war zone, but I’m not interested in war, I’m interested in having a good time. And pretty girls. I was using and abusing the fashion industry to my advantage.

You worked with Anna Wintour long before she became the editor at Vogue. At that time could you tell she was destined for great things in the fashion world?

She was actually very shy and quiet, but creatively adventurous, with a great eye and style.

The narratives of your stories are very strong, captivating, and complex. Where do your ideas for these images come from? Do you work the way filmmakers do, using a storyboard?

The content itself must come from my life in some form. My ideas come from a need to say something, to the point where I have to take my camera out to say it. My ideas always have a personal, social or political commentary because the main thing I want is for people to think. I want people to ask questions about why I made the picture.

As far as storyboards, I have mental ones. Sometimes I will draw a stick figure to explain something to others. But I try to keep the information in my head before I shoot so that there is a sense of spontaneity at the actual shoot. I feel that the image comes across better this way.

Some describe your pictures as film stills, and so the logic would follow that your models are more like actors. Does it take a certain type of model to achieve the picture you are striving for? Could you talk a bit about the dynamics of an assignment?

Well to be an honest, I was a model’s nightmare because models just want to be the center of the picture and look beautiful, but my models are just one little piece of a much bigger picture. But in the end most of the models respected my work and ideas because they were different. I didn’t treat them as actors, but as human beings. I wanted them to feel the emotion of the scene.

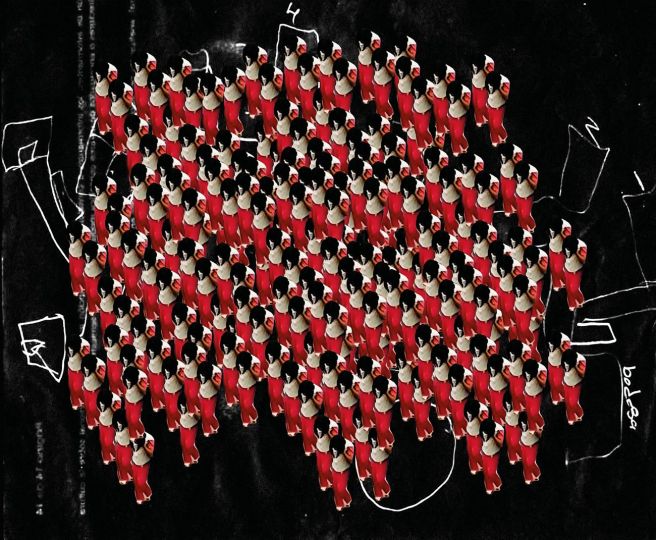

Do you have certain pictures that you would call your favorites, or ones that are most meaningful to you?

I think Vietnam is my favorite picture because it has all of the elements we have been talking about. The women are real, with bodies, and strength; the dress is beautiful, the action is there, and the ambiguity of the story is there as well. You don’t know exactly where you are in the content.

I heard that you are currently writing the story of your life. When you look back, do you see your life in cinematic terms, as you have seen your pictures? How will writing your own story affect your future work?

I am absolutely writing it like a film. The story is not linear, I am writing it all over the place because I think that makes it more interesting. I don’t suspect it will change my work, I think it will just make me realize how bad of a writer I am.

This interview is part of a series conducted by Holden Luntz Gallery, based in Palm Beach, Florida.

Interviewer: Sara Tasini

Holden Luntz Gallery

332 Worth Ave

Palm Beach, FL 33480

USA